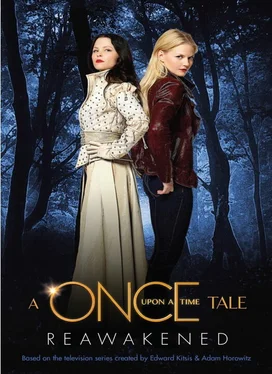

— That’s your smoking gun? — Emma said, looking at the illustration. — There are other Emma's in the world, you know. — Emma took the pages from him and looked through them, searching for an author name or a copyright date. But there was nothing — no date, no author. Maybe in the book itself. It was anyone’s guess where the thing came from. Either way, though, quite a coincidence that the baby had that blanket. It reminded her of the one she had had with her when she was found, the one she carried through all the foster homes. She still had it somewhere, packed away in a box back in Boston. It wasn’t the type of memento she liked to pull out, though. Most of the memories that came along with it were painful.

— I think you should read all of the pages, — Henry said. — This part is your story. I know you’re not going to believe me until you do. — He nodded to himself, then said, — You can’t let her see these pages, though. You can’t. That’s why I ripped them out. It would be… very bad.

Emma looked at the book.

— Really? — she said, looking at a picture of the Queen. It did look a little like Regina; she could see how Henry could have convinced himself of all this.

Sort of.

— Really bad, — he said. — Really really really bad.

Emma and Henry soon reached the school. Before he left, he looked up and smiled and said, — Thanks for believing me about the curse. I knew that you would. — It almost killed her, he was so much in earnest. No problem kid, I didn’t believe you at all!

— I didn’t say that I did, kid, — she said, thinking that it would probably be best to be honest, but a tempered honest. — I just listened. — That was totally true.

Still, Henry continued to smile, then turned and ran off toward class. Emma watched him go, still unsure how to handle his «interesting» relationship to reality. This «Operation Cobra» game seemed to give him endless joy, and some instinct told her it was never a bad thing for your child to feel joy. That was a mother’s job, wasn’t it? But a part of her thought that she was behaving recklessly, like the grandmother who steps in and gives the grandkid sweets until he’s sick. An outsider who is playing the game tor short-term gains, not long-term goals.

— It’s good to see him smiling.

Emma, startled, saw that Mary Margaret had approached.

— Oh. I guess it is, — she said. — I didn’t do that, though. Magic did.

— Does Regina know that you’re still here?

— Yes. She charmed me this morning with an angry speech. Really, really pleasant. How did that woman ever get elected to public office? She has no social skills.

— It seems like she’s always been mayor, — said Mary Margaret.

Emma looked at her and cocked an eyebrow.

— What do you mean?

— I think everyone is too scared of her to rim against her, — continued Mary Margaret. — And I’m afraid I only made things worse for Henry by giving him that book.

— Where did you get that book? — Emma asked.

— Hm, — said Mary Margaret. — I’m not totally sure. Here at the school, I think?

— And who does he think you are, by the way? — Emma asked.

— Me? It’s silly. — She smiled and looked down. — He actually thinks I’m — that I’m Snow White.

— Wow, Snow White, — Emma said and nodded, impressed. — Not bad.

— And who are you?

Emma looked at her, and didn’t want to say it once she realized what it implied about their relationship. Emma was surprised at how eagerly some part of her imagination entertained the idea, tried to dock with it, albeit for just a few seconds. It was just the kind of thing she used to do when she was a kid, a game she played by herself. Making Up Mom was what she called it, even though she never told anybody what it was she was doing for all those hours, hiding in closets or tucked in a ball beneath a tree. She spent that time envisioning what her mother was like — who she was, where she was, why she’d been forced to give Emma up for adoption. The fantasizing had eventually cohered, over a couple of years, into one blurry image in her mind that was almost a memory. The woman was smiling and coming toward her with her arms out, saying, «Emma, Emma,» in a sweet, tender voice. It was silly. Made up. It was all stupid. She’d realized that when she was eleven or twelve, and had quit playing the game then. Forever.

— Me? Oh, I’m not in the book.

— That’s right, — said Mary Margaret. — You’re from someplace else.

Emma smiled.

— But I do have to go see Jiminy Cricket.

Mary Margaret frowned.

— His doctor. Archie, — explained Emma. — Know where I can find him?

She did, and Emma walked through town to Archie’s offices, wondering if it was wise for her to get involved in Henry’s therapy, but unable to stop herself either way. Most likely he wouldn’t be able to tell her anything. But then again, she was Henry’s mother…

Strange how easily she’d settled into thinking of herself as Henry’s mother, and she thought again of the moment with Mary Margaret, the leap of believing. In Henry’s case, it was true, she was his mother, but still, the concept was the same, wasn’t it? You don’t know something, then you find it out, and blam! You start to rethink everything. She had to be careful. There were soft spots in her psyche, ways in which she was vulnerable in this place. For so many years she’d developed armor, and now, in just a couple of days, the chinks were showing up. If enough of them did, eventually someone would exploit them.

At the door, Archie smiled and said hello, invited her into his small office. As she strolled in, Emma told him that she needed to talk about Henry.

— Oh, no, no, ethically I really can’t…

— I know, I know. I get it. Doctor-patient privilege. I just want to know one thing. Maybe you can bend the rules.

Archie relaxed, crossed his arms.

— What is it?

— What causes it? — Emma asked.

That simple question had been on her mind all morning.

— Why is he confused about what’s real? Is he…crazy? Or is it just his imagination? I guess I need to know if he’s sick, or diseased, or just… I don’t know. What is the actual diagnosis?

Archie looked pained by the question, especially by her use of the word «crazy». He adjusted his glasses nervously, shook his head some more, and walked her over to his desk. — Please don’t talk like that to him — please don’t tell him you think he’s crazy, that would be terrible. — He motioned for her to sit down; he sat as well. — These stories are his language. Think of it that way. This is how he communicates with the world right now. He’s been through so much. This is him communicating, Ms.Swan. That’s a good thing.

— He’s dealing with his problems.

— That’s right.

— What are his problems, then? — The logical follow-up.

Archie seemed to realize where she was going. He pursed his lips, tilted his head.

— It’s Regina, isn’t it? She’s making him unhappy?

— No, no, that’s an overstatement, far too reductive, — said Archie. — Of course not. She’s a complicated woman and a stern mother, but she’s a good mother, too. — He nodded as he said this, Emma noted. He appeared to believe it. — What is your relationship like with your mother? Do you see my point?

Another arrow to the heart

— You obviously haven’t read the morning’s newspaper, — Emma said.

— What do you mean?

— I’m adopted, too, — she said. — I don’t know my mother.

— Oh, — Archie said quietly, as though this made sense to him. He nodded to himself, touched his chin. — I see. Well. You understand the point. Relationships with mothers are always complicated. — He smiled. — Fathers, too.

Читать дальше