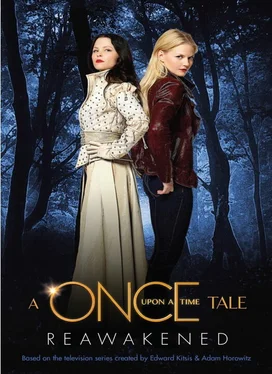

Her reverie was interrupted by what she saw across the street: Emma Swan, Henry’s birth mother, sat in the front seat of her yellow VW Bug, poring through a newspaper.

Mary Margaret smiled, crossed the street, and tapped on the window.

— You decided to stay in town for Henry, — Mary Margaret said. — Didn’t you? — She admired it. She couldn’t imagine what it would be like, but she admired it.

— Either way, I decided to stay, — Emma said, stretching her legs. — What I can’t believe is that there are no places to rent in this town. — She held up the newspaper. — And no jobs. What gives?

— I’m not sure, — Mary Margaret said. — People like things to stay the same around here, I suppose.

— What’re you doing out?

Mary Margaret crossed her arms.

— I was on an unsuccessful date, thank you very much.

Emma nodded.

— One of those, — she said. — I know them well.

— No one ever said true love was easy, right? — Mary Margaret said. Emma nodded again, and Mary Margaret thought she saw something in her eyes — something about true love, maybe, that hurt her — and she suddenly felt terrible. Why was she always talking herself into corners?

— Well, — Emma said. — Have a good night. I’ll just go back to my office.

— You know you could stay at my place, — Mary Margaret said suddenly. It surprised her, but as the offer hung in the air between the two women, she decided that it felt right, somehow. That it would work. That they’d get along just fine.

She offered a follow-up smile and added: — I mean just until you get your feet on the ground.

— That is, um, very nice of you, — Emma said, — but I gotta say, I’m not really the roommate type. No offense. You know? But that’s nice of you, really. I appreciate it.

— Of course, — said Mary Margaret. She took one step back. — Of course. Whatever works.

They separated, and Mary Margaret went home, trying to distance herself from the feeling of being rejected two times in one night. Tomorrow she would volunteer at the hospital. The people there, at least, would be happy to have her around.

What had possibly compelled her to make that offer to a perfect stranger? She didn’t know. Not for the life of her.

* * *

— I found your father.

Sitting next to Henry on his castle’s top platform, her legs dangling down, Emma looked over at him.

— Excuse me? — she said.

It was Saturday, but Regina was busy all day, which meant that Emma and Henry could spend some time together. She’d met him out here before, and this seemed best, really. No reason to involve Regina, no reason to make it messy.

— I seriously doubt that, kid, — Emma said.

Because she had tried, once, to find him. To find both of them. She hadn’t gotten very far, as the circumstances of her own abandonment as a baby were a tad murky. There was nothing. Zilch. There wasn’t a chance in hell this kid knew anything she didn’t know.

— No, I did, — Henry insisted. — He’s here, he’s in town. — He twisted and picked up his book. Emma glanced up at the sky quickly, realizing what he meant. It just kept going and going.

— Look, — Henry said, flipping to a page that showed a man — a handsome man, strong-jawed, eyes closed, bleeding from the chin — lying in the grass. — It’s Prince Charming. After Snow White hits him and gets away.

— What kind of twisted version of Snow White are you reading here, kid? — Emma asked, taking the book. She flipped back a few pages and let her eyes wander across the text.

— It’s complicated, — Henry said, — but the point is that he’s here, and he’s Miss Blanchard’s true love, and she doesn’t even know that he’s here. I saw him. In the hospital. He’s been in a coma for years.

Emma flipped back to the picture.

— This guy? — she said, pointing.

— His name is John Doe, — Henry said.

— So they don’t know who he is.

— That’s right, but I know, — he said. — And now you know. And we have to get him to wake up so he remembers who Ms. Blanchard is.

Emma was settling into her strategy of going along with what Henry said. The next question came pretty naturally: — How are we supposed to do that?

— I thought of that already, — Henry said. — All we have to do is get her to read this story to him.

— What story is it?

— The story of them falling in love, — Henry said. — It’s important.

Emma said nothing, just looked out at the water.

— What? — Henry said. — Don’t you think that it is?

— I do, actually, — Emma said. — Believe it or not. I completely do.

Henry smiled his beaming, irresistible smile.

— So you’ll help.

— Sure, — she said. — But we’re doing it my way. Not your way. My way. Got it?

* * *

— Let me get this straight, — Mary Margaret said, eyeing Emma skeptically. — You want me to read the same children’s stories I gave to Henry to John Doe? Who’s been in a coma for years? At the hospital?

— That’s right

— And you want me to do this because Henry thinks the story will wake him up, because he is Prince Charming, and I am Snow White, and we are soul mates, and true love can conquer the curse?

— Yup, — Emma said, nodding and biting into her celery one more time. — That’s pretty much it.

— That’s nuts.

Emma cocked her head.

— A little, — she said. — But not that nuts.

They were at Mary Margaret’s apartment, both of them sitting on the couch. Mary Margaret was glad when Emma knocked on the door, and initially she’d thought it was about the offer to be roommates, but Emma — who was always a straight shooter, it seemed — launched right into the plan about the anonymous man at the hospital. It was all ridiculous. But Mary Margaret studied the strange woman, thinking about the plan’s implications, what it would mean. She was right. Maybe not so nuts.

— And what you didn’t say, — Mary Margaret said, — was that he won’t wake up, Henry will see that, and it will be a gentle way of showing him that he might be wrong about this curse of his.

Emma smiled a quick smile, bit again into her celery.

— Something like that, — she said.

And so Mary Margaret agreed. Why? There were many reasons. She liked Emma Swan; she liked the plan to help Henry; she liked the simple elegance of the solution. She liked, even, the opportunity to read to a patient — a handsome patient — in front of Dr. Whale. Yes, that part was silly, but if she was being honest, she’d have to admit that she had noticed John Doe several times, had walked past him and felt that quiet glimmer of familiarity rustle somewhere down in her mind. On her way into the hospital, book under her arm, she wondered if she liked John Doe because he was always there, always so consistent, always so reliable. No, he didn’t talk back, and no, he had no idea who she was, but he always stayed the same. He was like her. He was alone, and he was stuck here in Storybrooke.

It was incredible to her how little life seemed to change in the town. She had been here for so long, but each year, the children seemed to be the same, her mixed feelings about Storybrooke seemed to be the same, and her loneliness — some murky part of herself that simply did not believe that she was meant to be a homebody, to know nearly no one, to spend her nights alone, drinking tea — well, it never changed. Was Storybrooke stagnant or safe? It was both. Little things like this — visits to the hospital — were as much about occupying her time as they were about the work itself.

She sat herself down beside his bed, made herself comfortable, and opened the book.

Читать дальше