“Getting ready for your clash with destiny, perhaps?” Sommers answered.

“Maybe,” Arnott shrugged. “I’m not sure. I only know that when I was in Japan, it seemed all-important that I should turn myself into a fighting machine; and when we were isolated in that frozen fjord, the only thing that mattered was knowing how to cure skins and forge iron as it was first forged at the beginning of the iron age. But always, as soon as I achieved my aim—” he shrugged again and fell silent for a moment, then continued in a different vein:

“As for sports: when other kids were playing football or splashing around in the swimming pool, I was fooling about with archery and fencing, even medieval jousting! I’ve flown with the birds in a kite-frame of silk and aluminium; and I’ve donned fins and tanks of air to take me down to the bottom of the sea. But in all of these things, always destiny has given me the slip.”

“Yes, you’ve done a good many things, Paul,” Sommers agreed, “and you’ve certainly traveled a great deal, too. But why didn’t you ever try Egypt?”

“Egypt?” Arnott frowned and shrugged again. “Perhaps I’ve been pursuing destiny on the one hand and avoiding it on the other—like a cat chasing its own tail.” For a moment he mused silently, then:

“It’s the one place—the one thing—that I’ve always feared,” he admitted.

“You’re afraid of Egypt?” Sommers laughed. “Now you really have lost me!”

“It’s like a Shangri-la to me, Wilf, a Brigadoon!” Arnott turned in his seat to stare hard at his friend. “I’ve never been there, but I feel that I have. And I feel that my Egypt is still there. Not in this century, no, but in another time, another world. I feel—I’ve always felt—that I’m a sort of stranger here, in this century. And yet I’ve feared to go back, to visit Egypt now, today. I suppose I’m afraid of what I might find there.”

“So you believe that your fancies aren’t just daydreams after all but, well, memories of a sort?” Sommers glanced at him out of the corner of his eye.

“Something like that, yes,” Arnott nodded. “I’m sure that your father guessed as much without ever asking. Of course, I’ve never told anyone else about it. I much prefer to be seen as an eccentric rather than a downright lunatic! But I’ll tell you something: a few of those ideas of mine aren’t nearly so crazy as they’re cracked up to be.”

Sommers knew what he meant. During a recent drought, a chariot wheel had been found in the clay banks of the Blue Nile at Wad Medani. Although it had been in a very poor state of preservation, it could still be seen to be different in construction from other Egyptian wheels. Also, while fragmentary artifacts found in the same clay were plainly bronze age Egyptian or Nubian, the hub of the wheel had been of iron! Iron? In a wheel come down from an era many thousands of years before the Hittites were allegedly the first to forge iron in Asia Minor? How could that be? Or … was Arnott right about a prehistoric wheel and a “bronze age” use of iron?

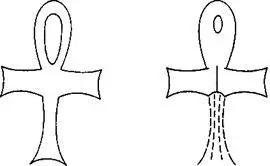

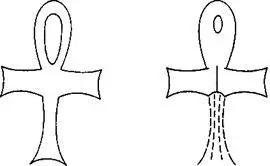

Then again, how could one take the man seriously? What of his rather more esoteric belief in visitors from outer space originating an Ancient Wisdom in pre-dynastic Egypt? Well, even in that area Arnott was not entirely alone in his thinking, though certainly his contemporaries were seen as charlatans and sensationalists. Sommers, for all that he must remain skeptical, could not help but remember an illustration Arnott had once drawn for Sir George. It was simply a picture of the ankh, the Egyptian symbol of generation; but alongside the conventional drawing Paul Arnott had drawn a second ankh, making it to look like something else entirely:

And what of the Egyptians themselves, the popular “Ancient” Egyptians as opposed to that earlier race of Arnott’s convictions? What were the real origins of their belief that the Pharaoh was a “son” of the sun god and his representative on earth? And why did they believe that his body had to be enshrined in a great tomb, a pyramid, in order that he might ascend to the sky to become one with his father ?

Why, if one’s imagination were sufficiently fertile, it might almost appear that Arnott’s—

“I’m accused of having been a wild one in my time,” his friend’s voice broke abruptly in on Sommers’s mental wanderings, “and perhaps I have been. But if I was then it sprang from my neverending sense of frustration. Doing the things I’ve done—the dangerous things, the risky things—was my way of escaping, of running from the mundane side of life. Perhaps my mother’s money spoiled me, I don’t know, but it let me do what I wanted to do when I wanted to do it. Then, when I found Julie ... she was the closest I’ve ever been to that dreamworld of mine, do you see? And yet it wasn’t really Julie at all. It was just the way she looked.”

“Like Sh’tarra, d’you mean?”

“Like Sh’tarra, yes. Like the face on that mask, that funerary mask from olden Kush. I have to see that mask, Wilf, hold it in my hands, feel it! The photograph brought things awake in me, raked over the embers, but I’m sure there are other memories that still lie dormant. I just have this feeling that the moment I lay my hands on that mask again—” And abruptly, he paused.

As the car drew to a halt at the curb outside the museum, the two men turned to stare at each other. They sat there like that, silently, for long moments. Then, with the slightest tremor in his voice, Sommers said what both of them were thinking:

“When you lay your hands on the mask ‘again,’ Paul?”

To which neither one of them had an answer….

The museum was a three-storied building standing central in an early Nineteenth Century street. Set back from the street proper, it stood close to the river, which could be seen from its higher windows. Its main entrance was through massive doors at the top of a flight of balustraded steps. Though one of these doors stood open, a sign clearly proclaimed the museum to be closed to the public for the afternoon. The last visitors had already left.

A museum of antiquities, the ground floor was filled with remnants of historic and prehistoric Britain; the first floor concerned itself with Ancient China, Mycenae, Peru, Crete and many other lands; but the second floor, where Sir George had his office and study, was the museum’s center of greatest interest. For that topmost floor was a small corner of Old Egypt, trapped and immobilized here in London, where all the magic of that ancient land was concentrated into an almost tangible essence within four walls of comparatively modern stone.

Climbing the stairs close behind his friend, Arnott said: “Will I get a chance to meet your mysterious Egyptian? I’d certainly like to talk to him.”

“That’s already been arranged,” Sommers answered. “He’s staying in London for the time being.”

“What’s his name?”

“He calls himself Omar Dassam.”

“And the Egyptian authorities simply let him bring the mask out of Egypt and into England? Why did he seek out Sir George ?”

Sommers coughed and answered, “He apparently smuggled the thing out! Being employed in the trade—as an agent for one of the big airlines— he had no difficulties. As to why he brought the mask to us—” he shrugged. “He says he ‘guessed’ we were the right ones to approach!”

Arnott frowned. “It all sounds too weird to be true. And what kind of a crazy trick was it to smuggle the thing out in the first place?”

Читать дальше