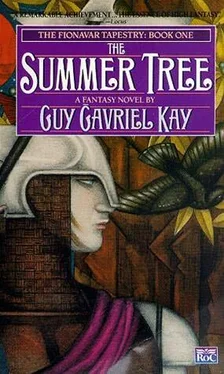

Guy Kay - The Summer Tree

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Guy Kay - The Summer Tree» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1984, Жанр: Фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Summer Tree

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:1984

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Summer Tree: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Summer Tree»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Summer Tree — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Summer Tree», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Holy Mother!” Dave exclaimed involuntarily.

It saved his life.

Of the nine tribes of the Dalrei, all but one had moved east and south that season, though the best grazing for the eltor was still in the northwest, as it always was in summer. The messages the auberei brought back from Celidon were clear, though: svart alfar and wolves in the edgings of Pendaran were enough for most Chieftains to take their people away. There had been rumors of urgach among the svarts as well. It was enough. South of Adein and Rienna they went, to the leaner, smaller herds, and the safety of the country around Cynmere and the Latham.

Ivor dan Banor, Chieftain of the third tribe, was, as often, the exception. Not that he did not care for the safety of his tribe, his children. No man who knew him could think that. It was just that there were other things to consider, Ivor thought, awake late at night in the Chieftain’s house.

For one, the Plain and the eltor herds belonged to the Dalrei, and not just symbolically. Colan had given them to Revor after the Bael Rangat, to hold, he and his people, for so long as the High Kingdom stood.

It had been earned, by the mad ride in terror through Pendaran and the Shadowland and a loop in the thread of time to explode singing into battle on a sunset field that else had been lost. Ivor stirred, just thinking on it: for the Horsemen, the Children of Peace, to have done this thing… There had been giants in the old days.

Giants who had earned the Plain. To have and to hold, Ivor thought. Not to scurry to sheltered pockets of land at the merest rumor of danger. It stuck in Ivor’s craw to run from svart alfar.

So the third tribe stayed. Not on the edge of Pendaran—that would have been foolhardy and unnecessary. There was a good camp five leagues from the forest, and they had the dense herds of the eltor to themselves. It was, the hunters agreed, a luxury. He noticed that they still made the sign against evil, though, when the chase took them within sight of the Great Wood. There were some, Ivor knew, who would rather have been elsewhere.

He had other reasons, though, for staying. It was bad in the south, the auberei reported from Celidon; Brennin was locked in a drought, and cryptic word had come from his friend Tulger of the eighth tribe that there was trouble in the High Kingdom. What, Ivor thought, did they need to go into that for? After a harsh winter, what the tribe needed was a mild, sweet summer in the north. They needed the cool breeze and the fat herds for feasting and warm coats against the coming of fall.

There was another reason, too. More than the usual number of boys would be coming up to their fasts this year. Spring and summer were the time for the totem fasts among the Dalrei, and the third tribe had always been luckiest in a certain copse of trees here in the northwest. It was a tradition. Here Ivor had seen his own hawk gazing with bright eyes back at him from the top of an elm on his second night. It was a good place, Faelinn Grove, and the young ones deserved to lie there if they could. Tabor, too. His younger son was fourteen. Past time. It might be this summer. Ivor had been twelve when he found his hawk; Levon, his older son—his heir, Chieftain after him—had seen his totem at thirteen.

It was whispered, among the girls who were always competing for him, that Levon had seen a King Horse on his fast. This, Ivor knew, was not true, but there was something of the stallion about Levon, in the brown eyes, the unbridled carriage, the open, guileless nature, even his long, thick yellow hair, which he wore unbound.

Tabor, though, Tabor was different. Although that was unfair, Ivor told himself—his intense younger son was only a boy yet, he hadn’t had his fasting. This summer, perhaps, and he wanted Tabor to have the lucky wood.

And above and beyond all of these, Ivor had another reason still. A vague presence at the back of his mind, as yet undefined. He left it there. Such things, he knew from experience, would be made clear to him in their time. He was a patient man.

So they stayed.

Even now there were two boys in Faelinn Grove. Gereint had spoken their names two days ago, and the shaman’s word began the passage from boy to man among the Dalrei.

There were two in the wood then, fasting; but though Faelinn was lucky, it was also close to Pendaran, and Ivor, father to all his tribe, had taken quiet steps to guard them. They would be shamed, and their fathers, if they knew, so it had been only with a look in his eye that he had alerted Tore to ride out with them unseen.

Tore was often away from the camps at night. It was his way. The younger ones joked that his animal had been a wolf. They laughed too hard at that, a little afraid. Tore: he did look like a wolf, with his lean body, his long, straight, black hair, and the dark, unrevealing eyes. He never wore a shirt, or moccasins; only his eltor skin leggings, dyed black to be unseen at night.

The Outcast. No fault of his own, Ivor knew, and resolved for the hundredth time to do something about that name. It hadn’t been any fault of Tore’s father, Sorcha, either. Just sheerest bad luck. But Sorcha had slain an eltor doe that was carrying young. An accident, the hunters agreed at the gathering: the buck he’d slashed had fallen freakishly into the path of the doe beside it. The doe had stumbled over him and broken her neck. When the hunters came up, they had seen that she was bearing.

An accident, which let Ivor make it exile and not death. He could not do more. No Chieftain could rise above the Laws and hold his people. Exile, then, for Sorcha; a lonely, dark fate, to be driven from the Plain. The next morning they had found Meisse, his wife, dead by her own hand. Tore, at eleven, only child, had been left doubly scarred by tragedy.

He had been named by Gereint that summer, the same summer as Levon. Barely twelve, he had found his animal and had remained ever after a loner on the fringes of the tribe. As good a hunter as any of Ivor’s people, as good even, honesty made Ivor concede, as Levon. Or perhaps not quite, not quite as good.

The Chieftan smiled to himself in the dark. That, he thought, was self-indulgent. Tore was his son as well, the whole tribe were his children. He liked the dark man, too, though Tore could be difficult; he also trusted him. Tore was discreet and competent with tasks like the one tonight.

Awake beside Leith, his people all about him in the camp, the horses shut in for the night, Ivor felt better knowing Tore was out there in the dark with the boys. He turned on his side to try to sleep.

After a moment, the Chieftain recognized a muffled sound, and realized that someone else was awake in the house. He could hear Tabor’s stifled sobbing from the room he shared with Levon. It was hard for the boy, he knew; fourteen was late not to be named, especially for the Chieftain’s son, for Levon’s brother.

He would have comforted his younger son, but knew it was wiser to leave the boy alone. It was not a bad thing to learn what hurt meant, and mastering it alone helped engender self-respect. Tabor would be all right.

In a little while the crying stopped. Eventually Ivor, too, fell asleep, though first he did something he’d not done for a long time.

He left the warmth of his bed, of Leith sound asleep beside him, and went to look in on his children. First the boys; fair, uncomplicated Levon, nut-brown, wiry Tabor; and then he walked into Liane’s room.

Cordeliane, his daughter. With a bemused pride he gazed at her dark brown hair, at the long lashes of her closed eyes, the upturned nose, laughing mouth… even in sleep she smiled.

How had he, stocky, square, plain Ivor, come to have such handsome sons, a daughter so fair?

All of the third tribe were his children, but these, these.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Summer Tree»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Summer Tree» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Summer Tree» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.