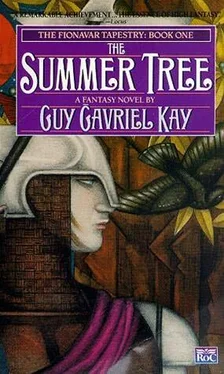

Guy Kay - The Summer Tree

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Guy Kay - The Summer Tree» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1984, Жанр: Фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Summer Tree

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:1984

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Summer Tree: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Summer Tree»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Summer Tree — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Summer Tree», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“You know why,” he heard himself say again. It had begun.

“Well, I did some thinking.”

“One should always do some thinking.”

“Paul, don’t be like—”

“What do you want from me?” he snapped. “What is this, Rach?”

So, so, so. “Mark asked me to marry him.”

Mark? Mark Rogers was her accompanist. Last-year piano student, good-looking, mild, a little effeminate. It didn’t fit. He couldn’t make it fit.

“All right,” he said. “That happens. It happens when you’ve got a common goal for a while. Theatre romance. He fell in love. Rachel, you’re easy to fall in love with. But why are you telling me this way?”

“Because I’m going to say yes.”

No warning at all. Point-blank. Nothing had ever prepared him for this kick. Summer night, but God, he was so cold. So cold, suddenly.

“Just like that?” Reflex.

“No! Not just like that. Don’t be so cold, Paul.”

He heard himself make a sound. A gasp, a laugh: halfway. He was actually shivering. Don’t be so cold, Paul .

“That’s just the sort of thing,” she said, twisting her hands together. “You’re always so controlled, thinking, figuring out. Like figuring out I needed to be alone a month, or why Mark fell in love with me. So much logic: Mark’s not so strong. He needs me. I can see the ways he needs me. He cries, Paul.”

Cries? Nothing held together anymore. What did crying have to do with it?

“I didn’t know you liked a Niobe number.” It was important to stop shivering.

“I don’t . Please don’t be nasty, I can’t handle it… Paul, it’s that you never truly let go, you never made me feel I was indispensable. I guess I’m not. But Mark… puts his head on my chest sometimes, after.”

“Oh, Jesus, Rachel, don’t!”

“It’s true!” It was raining harder. Trouble breathing now.

“So he plays harp, too? Versatile, I must say.” God, such a kick; he was so cold.

She was crying. “I didn’t want it to be…”

She didn’t want it to be like this. How had she wanted it to be? Oh, lady, lady, lady.

“It’s okay,” he found himself saying, incredibly.

Where had that come from? Trouble breathing still. Rain on the roof, on the windshield. “It’ll be all right.”

“No,” Rachel said, weeping still, rain drumming. “Sometimes it can’t be all right.”

Smart, smart girl. Once he would have reached to touch her. Once? Ten minutes ago. Only that, before the cold.

Love, love, the deepest discontinuity.

Or not quite the deepest.

Because this, precisely, was when the Mazda in front blew a tire. The road was wet. It skidded sideways and hit the Ford in the next lane, then rebounded and three-sixtied as the Ford caromed off the guard rail.

There was no room to brake. He was going to plough them both. Except there was a foot, twelve inches’ clearance if he went by on the left. He knew there’d been a foot, had seen the movie in slow motion in his head so many times. Twelve inches. Not impossible; very bad in rain, but.

He went for it, sliced the whirling Mazda, banged the rail, spun, and rolled across the road and into the sliding Ford.

He was belted; she wasn’t.

That was all there was to it, except for the truth.

The truth was that there had indeed been twelve inches, perhaps ten, as likely, fourteen. Enough. Enough if he had gone for it as soon as he saw the hole. But he hadn’t, had he? By the time he’d moved, there were three inches clear, four, not enough at night, in rain, at forty miles an hour. Not nearly.

Question: how did one measure time there, at the end? Answer: by how much room there was. Over and over he’d watched the film in his mind; over and over he’d seen them roll. Off the rail, into the Ford. Over.

Because he hadn’t moved fast enough.

And why— Do pay attention, Mr. Schafer— why hadn’t he moved fast enough?

Well, class, modern techniques now allow us to examine the thought patterns of that driver in the scintilla—lovely word, that—of time between the seeing and the moving. Between the desire and the spasm, as Mr. Eliot so happily put it once.

And where, on close examination, was the desire?

Not that we can be sure, class, this is most hazardous terrain (it was raining, after all), but careful scrutiny of the data does seem to elicit a curious lacuna in the driver’s responses.

He moved, oh, yes indeed, he did. And in fairness—do let’s be fair—faster than most drivers would have done. But was it—and there’s the rub—was it as fast as he could move?

Is it possible, just a hypothesis now, but is it possible that he delayed that scintilla of time—only that, no more; but still—because he wasn’t entirely sure he wanted to move? The desire and the spasm. Mr. Schafer, your thoughts? Was there perhaps a slight, shall we say, lag in the desire?

Dead on. St. Michael’s Emergency Ward.

The deepest discontinuity.

“It should have been me,” he’d said to Kevin. You had to pay the price, one way or another. You certainly weren’t allowed to weep. Too much hypocrisy, that would be. Part of the price, then: no tears, no release. What had crying to do with it? he had asked her. Or no, he had thought that. Niobe, he had said. A Niobe number. Witty, witty, defenses up so fast. Seatbelt buckled. So cold, though, he’d been, so very cold. Crying, it seemed, had a lot to do with it, after all.

But there was more. One played the tape. Over and over, like the inner film, like the rolling car: over and over, the tape of her recital. And one listened, always, in the second movement, for the lie. His, she had said. That part because she loved him. So it had to be a lie. One should be able to hear that, despite Walter Langside and everyone else. Surely one could hear the lie?

Not so. Her love for him in that sound, that perfect sound. Incandescent. And this was beyond him; how it could be done. And so each time there came a point where he couldn’t listen anymore and not cry. And he wasn’t permitted to cry, so.

So she had left him and he had killed her, and you weren’t allowed to weep when you have done that. You pay the price, so.

So he had come to Fionavar.

To the Summer Tree.

Class dismissed. Time to die.

This time it was the silence. Complete and utter stillness in the wood. The thunder had stopped. He was cinder, husk: what is left, at the end.

At the end one came back because, it seemed, this much was granted: that one would go in one’s own self, from this place, knowing. It was an unexpected dispensation. Drained, a shell, he could still feel gratitude for dignity allowed.

It was unnaturally silent in the darkness. Even the pulsing of the Tree itself had stopped. There was no wind, no sound. The fireflies had gone. Nothing moved. It was as if the earth itself had stopped moving.

Then it came. He saw that, inexplicably, a mist was rising from the floor of the forest. But no, not inexplicably: a mist was rising because it was meant to rise. What could be explained in this place?

With difficulty he turned his head, first one way, then the other. There were two birds on the branches, ravens, both of them. I know these, he thought, no longer capable of surprise. They are named Thought and Memory. I learned this long ago.

It was true. They were named so in all the worlds, and this was their nesting place. They were the God’s.

Even the birds were still, though, each bright yellow eye steady, motionless. Waiting, as the trees were waiting. Only the mist was moving; it was higher now. There was no sound. The whole of the Godwood seemed to have gathered itself, as if time were somehow opening, making a place—and only then, finally, did Paul realize that it was not the God they were waiting for, it was something else, not truly part of the ritual, something outside… and he remembered an image then (thought, memory) of something far back, another life it seemed, another person almost who had had a dream… no, a vision, a searching, yes, that was it… of mist, yes, and a wood, and waiting, yes, waiting for the moon to rise, when something, something…

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Summer Tree»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Summer Tree» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Summer Tree» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.