“Agsded is a wizard—a master mage, a master of masters. The mark on him is so bright it could blind any simple folk who look upon it, though they knew not what they saw. Agsded I knew long ago—he was another of Goriolo’s pupils; he was the best of all of us, and he knew it; but even Goriolo did not see how deep his pride went.—. . Goriolo had another pupil of Agsded’s family: his sister. She feared her brother; she had always feared him; it was fear of what his pride might do that led her to Goriolo with him, but it was on her own merit that Goriolo took her.

“And I—I must send you into the dragon’s den again, having barely healed you, and that at great cost, from your encounter with the Black Dragon. Maur is to your little dragons what Agsded is to Maur. I teach you what I may because it is the only shield I may—can—give you. I cannot face Agsded myself—I cannot. By the gods and hells you have never heard of,” Luthe broke out, “do you think I like sending a child to a doom like this, one I know I cannot myself face? With nothing to guard her but half a year’s study of the apprentice bits of magery?

“I know by my own blood that I cannot defeat him; though by some of that blood I have held him off these many years longer, that the chosen hero, the hero of his blood, might grow up to face him; for only one of his blood may defeat him.” Luthe closed his eyes. “It is true your mother wanted a son; she believed that as only one of his blood might defeat him, so only one of his own sex might, for to such she ascribed her own failure. She felt that it was because she was a woman that she could not kill her own brother.”

“Brother?” whispered Aerin.

Luthe opened his eyes. “Had she tried, she might yet have failed,” he went on as though he had not heard her, “but she could not bear to try; until Agsded, who knew the prophecy even as she did, from long before there was apparent need to know it, sought to bring her under his will or to destroy her.

“He could not do the former; almost he did the latter, and in the end she died of the poison he gave her.” Luthe looked at her, and she remembered the hand that was not her own holding a goblet, and a voice that was not Luthe’s saying “Drink.”

“But she had meanwhile fled south, and found a man with kelar in his blood, and been got with child by him. She had only the strength left to bear that child before she died.”

Luthe fell silent, and Aerin could think of nothing to say. Agsded beat in her brain; a moment ago she had told Luthe she did not know the name, and yet now she was ready to swear that it had haunted all the shadows since before her birth; that her mother had whispered it to her in the womb; that the despair she had died of was the taste of it on her tongue. Agsded, who was to Maur what Maur had been to her first dragon; and the first dragon might have killed her—and Maur had killed her, for the time she lived now was not her own. Agsded, of her own blood; her mother’s brother.

She felt numb; even the new sensitivities that had awoken in her since her dive into the Lake of Dreams and Luthe’s teaching—all were numb, and she hung suspended in a great nothingness, imprisoned there by the name of Agsded.

After a pause Luthe said, as if talking to himself: “I did not think your kelar would so hide itself from you. Perhaps it was the hurt you did yourself and your Gift by eating the surka. Perhaps your mother was not able entirely to protect the child she carried from the death so close to her. I believed that you had to know at least something of the truth—I believed it until I saw you face Maur with little more than simple human courage and a foolhardy faith in the efficacy of a third-rate healer’s potion like kenet against the Black Dragon. And I knew then not only that I was wrong about you, but that I was too late to save you from the pain your simplicity would cause you; and I feared that without your kelar to draw upon, you would not survive that meeting. And I was terribly near right.

“I have been much occupied while you were growing up, and I do not mark the years as you do; and I have not watched over you as I should have. As I promised your mother I would. Again I am sorry. I have been often sorry, with you, and there is so little I can do about any of it.

“I believed that you would grow up knowing some destiny awaited you; I thought what ran in your veins could not help but tell you so much. I thought you would know the true dreams I sent you as such. I thought many things that were wrong.”

“The kelar may have tried to tell me,” Aerin said dully; “but the message did get a little confused somehow. Certainly I was left in no doubt that my destiny was different than Arlbeth’s daughter’s should have been, but that was a reading anyone could have done.”

Luthe looked at her, and saw her uncle’s name like a brand on her face. “If you wish,” he said lightly, “I shall go personally to your City and knock together the heads of Perlith and Galooney.”

Aerin tried to smile. “I shall remember that offer.”

“Please do. And remember also that I never leave my mountain any more, so believe how apologetic I must be feeling to make it in the first place.”

Aerin’s smile disappeared. “Am I truly just as my mother was?” she asked, as she had asked Teka long ago.

Luthe looked at her again, and again many things crowded into his mind that he might say. “You are very like her,” he said at last. “But you are to be preferred.”

AFTER THIS, suddenly the winter was too short, despite the nightmares of a man with eyes brighter than a dragon’s, who wore a red cloak. The snow melted too soon, and too soon the first tight buds knuckled out from the trees, and the first vivid purple shoots parted the last year’s dry grass. There was a heavy rich smell in the air, and Aerin kept seeing things in the shadows just beyond the edge of sight, and hearing far high laughter she could not be sure she did not imagine. Sometimes when she saw or heard such somethings she would whip around to look at Luthe, who, as often as not, would be staring into the middle distance with a vague silly smile on his face.

“You aren’t really alone up here at all, are you?” she said, and was surprised to feel something she suspected was jealousy.

Luthe refocused his eyes to look at her gravely. “No. But my ... friends ... are very shy. Worse than I am.”

“I’ll be leaving soon anyway,” Aerin said. “They’ll come back to you soon enough.’’

Luthe did not answer immediately. “Yes. Soon enough,”

She got out Talat’s saddle and gear and cleaned everything, and oiled the leather; and upon request Luthe provided her with some heavy canvas and narrow bits of leather, and she rigged a plain breastplate, for Talat had insufficient wither to carry a saddle reliably straight. She also made a little leather pouch to carry the red dragon stone, which had been living under a corner of her mattress, and hung it around her neck on a thong. Then she spent hours currying Talat while the winter hair rose in clouds around them and Talat made hideous faces of ecstasy and gratification.

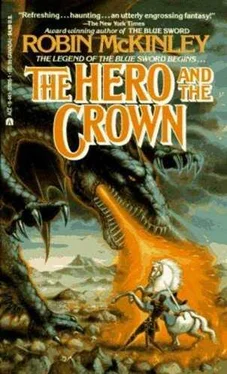

She came dripping into the grey hall at twilight one evening, having shed a great deal of white hair and dust in the bathhouse, and found Luthe pulling the wrappings off a sword. The cloth was black and brittle, as if with great age, but the scabbard gleamed silver-white and the great blue gem set in the hilt was bright as fire. “Oh,” breathed Aerin, coming up behind him.

He turned and smiled at her, and, holding the scabbard in a shred of ragged black cloth, offered her the hilt. She grasped it without hesitation, and the feel of it was as smooth as glass, and the grips seemed to mold to her hand. She pulled the blade free, and it flashed momentarily with a light that cut the farthest shadows of Luthe’s ever shadowed hall, and there seemed to be an echo of some great clap of sound that deafened both the red-haired woman and the tall blond man; yet neither heard anything. And then it was merely a sword, glinting faintly in the firelight, with a great blue gem set at the peak of the hilt.

Читать дальше