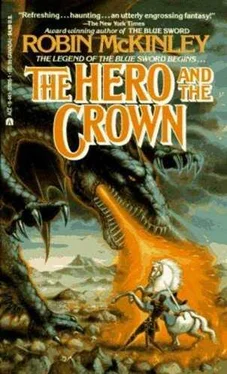

Luthe pulled a handful of leaves off the surka and began to weave them together. “It’s what your family calls the Gift. They haven’t much of it left to call anything. You’re stiff with it—be quiet. I’m not finished—for all you tried to choke me off by an overdose of surka.” He eyed her. “Probably you will always be a little sensitive to it, because of that; but I still believe you can learn to control it.”

“I was fifteen when I ate the surka and—”

“The stronger the Gift, the later it shows up, only your purblind family has forgotten all that, not having had a strong Gift to deal with in a very long time. Your mother’s was late. And your uncle’s,” He frowned at the wreath in his hands.

“My mother.”

“Most of your kelar is her legacy.”

“My mother was from the North,” Aerin said slowly. “Was she then a witch—a demon—as they say?”

“She was no demon,” Luthe said firmly. “A witch? Mmph. Your village elders, who sell poultices to take off warts, are witches.”

“Was she human?”

Luthe didn’t answer immediately. “That depends on what you mean by human.”

Aerin stared at him, all the tales of her childhood filling her eyes with shadows.

Luthe was wearing his inscrutable look again, although he bent it only on the surka wreath. “Time was, you know, there were a goodly number of folk not human who walked this earth. Time was—not so long ago. Those who were human, however, never liked the idea, and ignored those not human when they met them, and now they ...” The inscrutable look faded, and he looked up from his hands and into the trees, and Aerin remembered the creatures on the walls of her sleeping-hall.

“I’m not,” he said carefully, “the best one to ask questions about things like humanity. I’m not entirely human myself.” He glanced at her. “Time I fed you again.”

She shook her head, but her stomach roared at her; it had been almost ceaselessly hungry since she had swum in the silver lake. Luthe seemed to take a curious ironic pleasure in pouring food into her; he was an excellent cook, but it didn’t seem to have much to do with culinary pride. It was more as if a mage’s business did not often extend to the overseeing of convalescents, and the interest he took in his humble role of provider ought to be beneath his dignity, and he was a little sheepish to discover that it wasn’t.

“Aerin.” She looked up, but the shadows of her childhood were still in her eyes. He smiled as if it hurt him and said, “Never mind.” And threw the surka wreath over her head. It settled around her shoulders and then rippled into long silver folds that fell to her feet, and shivered like starlight when she moved.

“You look like a queen,” Luthe said,

“Don’t,” she said bitterly, trying to find a clasp to unfasten the bright cloak. “Please don’t.”

“I’m sorry,” said Luthe, and the cloak fell away, and she held only silver ashes in her hands. She let her hands fall to her sides, and she felt ashamed. “I’m sorry too. Forgive me.”

“It matters nothing,” Luthe said, but she reached out and hesitantly put a hand on his arm, and he covered it with one of his. “There may have been a better way than the Meeldtar’s to save your life,” he said. “But it was the only way I knew; and you left me no time. ... I was not trained as a healer.” He shut his eyes, but his hand stayed on hers. “No mages are, usually. It’s not glamorous enough, I suppose; and we’re a pretty vain lot.” He opened his eyes again and tried to smile.

“Meeldtar is the Water of Sight, and its spring runs into the lake here, the Lake of Dreams. We live—here—very near the Meeldtar stream, but the lake also touches other shores and drinks other springs—I do not know all their names. I told you I’m not a healer ... and . . , when you got here, finally, I could almost see the sunlight through you. If it weren’t for Talat, I might have thought you were a ghost. The Meeldtar suggested I give you a taste of the lake water—the Water of Sight itself would only have ripped your spirit from what was left of your body.

“But the lake—even I don’t understand everything that happens in that lake.” He fell silent, and dropped his hand from hers, but his breath stirred the hair that fell over her forehead. At last he said: “I’m afraid you are no longer quite .. .mortal.”

She stared up at him, and the shadows of her childhood ebbed away to be replaced by the shadows of many unknown futures.

“If it’s any comfort, I’m not quite mortal either. One does learn to cope; but within a fairly short span one finds oneself longing for an empty valley, or a mountain top. I’ve been here ...”

“Long enough to remember the Black Dragon.”

“Yes. Long enough to remember the Black Dragon.”

“Are you sure?” she whispered.

“One is never sure of anything,” he snapped; but she had learned that his anger was not directed at her, but at his own fears, and she waited. He closed his eyes again, thinking. She’s being patient with me. Gods, what has happened to me? I’ve been a master mage since old Goriolo put the mark on me, and he could almost remember when the moon was first hung in the sky. And this child with her red hair looks at me once with those smoky feverish eyes and I panic and dunk her in the lake. What is the matter with me?

He opened his eyes again and looked down at her. Her eyes were still smoky, green and hazel, still gleaming with the occasional amber flame, but they were no longer feverish, and their calm shook him now almost as badly as their dying glitter had done. “I followed you, you know, when you went under. I—I had to make a rather bad bargain to bring you back again. It was not a bargain I was expecting to have to make.” He paused. “I’m pretty sure.”

The eyes wavered and dropped. She looked at her one hand tucked over Luthe’s arm, and brought the other up to join it; and gently, as if she might like his comfort no better than she had liked his gift, he put his other arm around her; and she leaned slowly forward and rested her head against his shoulder. “I’m sorry,” he said.

She laughed the whisper of a laugh. “I was not ready to die yet; very well, I shall live longer than I wished.”

She stirred, and moved away from him, and her arms dropped; but when he took one of her hands she did not try to withdraw it. The wind rustled lightly in the leaves. “You promised me food,” she said lightly.

“I did. Come along, then.”

The way back to Luthe’s hall was narrow, and as they walked side by side, for Luthe would not relinquish her hand, they had to walk very near each other. Aerin was glad when she saw the grey stone of the hall rear up before her, and at the edge of the small courtyard she broke away from the man beside her, and ran up the low steps and into the huge high room; and by the time he rejoined her she was busily engaged in pretending to warm her hands at the hearth. But she had no need of the fire’s warmth, for her blood was strangely stirred, and the flush on her face was from more than the fire’s red light.

Over supper she said, “I have not heard anyone else call it kelar. Just the Gift, or the royal blood.”

He was grateful that she chose to break the silence and answered quickly: “Yes, that’s true enough, although your family made themselves royalty on the strength of it, not the other way round. It came from the North originally.” He smiled at her stricken look. “Yes, it did; you and the demon-kind share an ancestor, and you have both lived to bear kelar through many generations. You need that common ancestor; without the unphysical strength the kelar grants you, you could not fight the demonkind, and Damar would not exist.”

Читать дальше