“Good. If you had remained hidden, I would have sent Gebeth again—and think of the honor you would have lost.”

Aerin, who seemed to have lost her voice instead, nodded again.

“Another lesson for you, my dear. Royalty isn’t allowed to hide—at least not once it has declared itself.”

A little of her power of speech came back to her, and she croaked, “I have hidden all my life.”

Something like a smile glimmered in Arlbeth’s eyes. “Do I not know this? I have thought more and more often of what I must do if you did not stand forth of your own accord. But you have—if not quite in the manner I might have wished—and I shall take every advantage of it.”

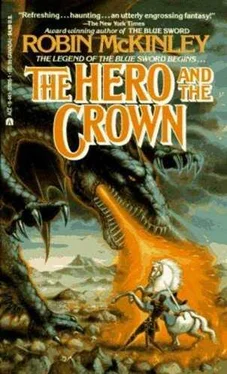

The second dragon-slaying went better than had the first. Perhaps it was her father’s spears, which flew truer to their marks than she thought her aim and arm deserved; perhaps it was Talat’s eagerness, and the quickness with which he caught on to what he was to do. There was also only one dragon.

This second village was farther from the City than the first had been, so she stayed the night. She washed dragon blood from her clothing and skin—it left little red rashy spots where it had touched her—in the communal bathhouse, from which everyone had been debarred that the sol might have her privacy, and sleeping in the headman’s house while he and his wife slept in the second headman’s house. She wondered if the second headman then slept in the third’s, and if this meant eventually that someone slept in the stable or in a back garden, but she thought that to ask would only embarrass them further. They had been embarrassed enough when she had protested driving the headman out of his own home. “We do you the honor fitting your father’s daughter and the slayer of our demon,” he said.

She did not like the use of the word demon; she remembered Tor saying that the increase of the North’s mischief would increase the incidence of small but nasty problems like dragons. She also wondered if the headman did not wish himself or his pregnant wife to spend a night under the same roof as the witchwoman’s daughter, or if they would get a priest in—the village was too small to have its own priest—to bless the house after she left. But she did not ask, and she slept atone in the headman’s house.

The fifth dragon was the first one that marked her. She was careless, and it was her own fault. It was the smallest dragon she had yet faced, and the quickest, and perhaps the brightest; for when she had pinned it to the ground with one of her good . spears and came up to it to chop off its head, it did not flame at her, as dragons usually did. It had flamed at her before, with depressingly little result, from the dragon’s point of view. When she approached it, it spun around despite the spear that held it, and buried its teeth in her arm.

Her sword fell from her hand, and she hissed her indrawn breath, for she discovered that she was too proud to scream. But not screaming took nearly ail her strength, and she looked, appalled, into the dragon’s small red eye as she knelt weakly beside it. Awkwardly she picked up her sword with her other hand, and awkwardly swung it; but the dragon was dying already, the small eye glazing over, its last fury spent in closing its jaws on her arm. It had no strength to avoid even a slow and clumsy blow, and as the sword edge struck its neck it gave a last gasp, and its jaws loosened, and it died, and the blood poured out of Aerin’s arm and mixed on the ground with the darker, thicker blood of the dragon.

Fortunately that village was large enough to have a healer, ‘and he bound her arm, and offered her a sleeping draught which she did not swallow, for she could smell a little real magic on him and was afraid of what he might mix in his draughts. At least the poultice on her arm did her good and no harm, even if she got no sleep that night for the sharp ache of the wound.

At home, pride of place and Arlbeth’s encouragement brought her to attend more of the courts and councils that administered the country that Arlbeth ruled. “Don’t let the title mislead you,” Arlbeth told her. “The king is simply the visible one. I’m so visible, in fact, that most of the important work has to be done by other people.”

“Nonsense,” said Tor.

Arlbeth chuckled. “Your loyalty does you honor, but you’re in the process of becoming too visible to be effective yourself, so what do you know about it?”

The most important thing that Aerin learned was that a king needed people he could trust, and who trusted him. And so she learned all over again that she lacked the most important aspect of her heritage, for she could not trust her father’s people, because they would not trust her. It was not a lesson she learned gratefully. But she had come out of hiding, and just as she could not scream when the dragon bit her, so she could not go back to her former life.

And the reports of dragons did increase, and thus she was oftener not at home, and so her excuse for eluding royal appearances was often the excellent one of absence, or of exhaustion upon too recent return. And she grew swifter and defter in dispatching the small dangerous vermin, and lost no more than a lock of hair that escaped her kenet-treated helmet to the viciousness of the creatures she faced. And the small villages came to love her, and they called her Aerin Fire-hair, and were kind to her, and not only respectful; and even she, wary as she was of all kindness, stopped believing that the headmen asked priests to drive out the aura of the witch-woman’s daughter after she left them.

But killing dragons did her no good with her father’s court; the soft-skinned ministers who worked in words and traveled by litter and could not hold a sword still mistrusted her, and privately felt that there was something rather shameful about a sol killing dragons at all, even a half-blood sol. Their increasing fear of the North only increased their mistrust of her, whose mother had come from the North; and her dragon-slaying, especially when the only wound she bore from a task that often killed horses and crippled men was a simple flesh wound, began to make them fear her; and the story of the first sola’s infatuation, which had begun to fade as nothing more came of it, was brought up again, and those who wished to said that the king’s daughter played a waiting game. They knew the story of the kenet, knew that anyone might learn the making of the stuff who wished to learn it; but why was it Aerin-sol who had found it out?

No one but Arlbeth and Tor asked her to teach them.

Perlith one night, after a great deal of wine had been drunk, amused the company by singing a new ballad that, he said, he had recently heard from a minstrel singing in one of the smaller dingier marketplaces in the City. She had been a rather small and dingy minstrel as well, he added, smiling, and she had been traveling through some of the smaller dingier villages of the Hills of late, which is where the ballad came from.

The ballad told of Aerin Fire-hair, whose hair blazed brighter than dragonfire, and thus she stew them without hurt to herself, for the dragons were ashamed when they saw her, and could not resist her. Perlith had a sweet light tenor voice, and the ballad was not so very badly composed, and the tune was an old and venerable one that many generations had enjoyed. But Perlith mocked her with it by the most delicate inflections, the gentlest ironies, and her knuckles were white around her wine goblet as she listened.

When Perlith finished, Galanna gave one of her bright little laughs. “How charming,” she said. “To think—we are living with a legend. Do you suppose that anyone will make up songs about any of the rest of us, at least while we are alive to enjoy them?”

“Let us hope that at least any songs made in our honor do not expose us so terribly,” Perlith said silkily, “as this one explains why our Aerin kills her dragons so easily.”

Читать дальше