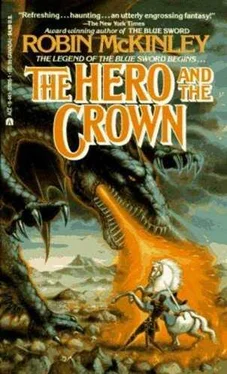

“I—er—I’ve gotten rid of the dragons already, if that’s what you mean,” said Aerin.

Gebeth dismounted, slowly, and slowly stooped down to __stare at her trophies. The jaws of one were open, and the sharp teeth showed. Gebeth was not a rapid nor an original thinker, and he remained squatting on his heels and staring at the grisly heads long after he needed only to verify the dragonness of them. As slowly as he had stooped he straightened up again and bowed, stiffly, to Aerin, saying, “Lady, I salute you.” His fingers flicked out in some ritual recognition or other, but Aerin couldn’t tell which salute he was offering her, and rather doubted he knew which one he wanted to give. “Thank you,” she said gravely.

Gebeth turned and caught the eye of one of his men, who dismounted and wrapped the heads up again; and then, as Gebeth gave no further hint, hesitated, and finally approached Talat to tie the bundle behind Aerin’s saddle.

“May we escort you home, lady?” Gebeth said, raising his eyes to stare at Talat’s pricked and bridleless ears, but carefully avoiding Aerin’s face.

“Thank you,” she said again, and Gebeth mounted his horse, and turned it back toward the City, and waited, that Aerin might lead; and Talat, who knew about the heads of columns, strode out without any hint from his rider.

The villagers, not entirely sure what they had witnessed, tried a faint cheer as Talat stepped off; and the boy who announced arrivals suddenly ran forward to pat Talat’s shoulder, and Talat dropped his nose in acknowledgment and permitted the familiarity. A girl only a few years older than the boy stepped up to catch Aerin’s eye, and said clearly, “We thank you.”

Aerin smiled and said, “The honor is mine.”

The girl grew to adulthood remembering the first sol’s smile, and her seat on her proud white horse.

IT WAS A SILENT journey back, and seemed to take forever. When they finally entered the City gates it was still daylight, although Aerin was sure it was the daylight of a week since hearing the villagers1 petition to her father for dragon-slaying. The City streets were thronged, and while the sight of seven of the king’s men in war gear and carrying dragon spears was not strange, the sight of the first sol riding among them and looking rather the worse for wear was, and their little company was the subject of many long curious looks. They can see me just fine coming home again, Aerin thought grimly. Whatever shadow it was that I rode away in, I wish I knew where it had gone.

Hornmar himself appeared at her elbow to take Talat off to the stables when they arrived in the royal courtyard. Her escort seemed to her to dismount awkwardly, with a great banging of stirrups and creak of girths. She pulled down the bundles from behind Talat’s saddle and squared her shoulders. She couldn’t help looking wistfully after the untroubled Talat, who readily followed Hornmar in the direction he was sure meant oats; but she jerked her attention back to herself and found Gebeth staring at her, frozen-faced, so she led the way into the castle.

Even Arlbeth looked startled when they all appeared before him. He was in one of the antechambers of the main receiving hall , and sat surrounded by papers, scrolls, sealing wax, and emissaries. He looked tired. Not a word had passed between Aerin and her unwilling escort since they had left the village, but Aerin felt that she was being herded and had not tried to .escape. Gebeth would have reported to the king immediately upon his return, and so she must; it was perhaps just as well that she had so many sheepdogs to her one self-conscious sheep, because she might have been tempted to put off the reckoning had she ridden back alone.

“Sir,” she said. Arlbeth looked at Aerin, then at Gebeth and Gebeth’s frozen face, then back at Aerin.

“Have you something to report?” he said, and the kindness in his voice was for both his daughter and his loyal, if scandalized, servant.

Gebeth remained bristling with silence, so Aerin said: “I rode out alone this morning, and went to the village of Ktha, to ... engage their dragon. Or—um—dragons.”

What was the proper form for a dragon-killing report? She might have paid a little more attention to such things if she’d thought a little further ahead. She’d never particularly considered the after of killing dragons; the fact that she’d done it was supposed to be enough. But now she felt like a child caught out in misbehavior. Which at least in Gebeth’s eyes she was. She unwrapped the bundle she carried under her arm, and laid the battered dragon heads on the floor before her father’s table. Arlbeth stood up and came round the edge of the table, and stood staring down at them with a look on his face not unlike Gebeth’s when he first recognized what was lying in the dust at his horse’s feet.

“We arrived at the village ... after,” said Gebeth, who chose not to look at Aerin’s ugly tokens of victory again, “and I offered our escort for Aerin-sol’s return.”

At “offered our escort” a flicker of a smile crossed Arlbeth’s face, but he said very seriously, “I would speak to Aerin-sol alone.” Everyone disappeared like mice into the walls, except they closed the doors behind them. Gebeth, his dignity still outraged, would say nothing, but no one else who had been in the room when Aerin told the king she had just slain two dragons could wait to start spreading the tale.

Arlbeth said, “Well?” in so colorless a tone that Aerin was afraid that, despite the smile, he must be terribly angry with her. She did not know where to begin her story, and as she looked back over the last years and reminded herself that he had set no barriers to her work with Talat, had trusted her judgment, she was ashamed of her secret; but the first words that came to her were: “I thought if I told you first, you would not let me go.”

Arlbeth was silent for a long time. “This is probably so,” he said at last. “And can you tell me why I should not have prevented you?”

Aerin exhaled a long breath. “Have you read Astythet’s History ?”

Arlbeth frowned a moment in recollection. “I ... believe I did, when I was a boy. I do not remember it well.” He fixed her with a king’s glare, which is much fiercer than an ordinary mortal’s. “I seem to remember that the author devotes a good deal of time and space to dragon lore, much of it more legendary than practical.”

“Yes,” said Aerin. “I read it, a while ago, when I was ... ill. There’s a recipe of sorts for an ointment called kenet, proof against dragonfire, in the back of it—”

Arlbeth’s frown returned and settled. “A bit of superstitious nonsense.”

“No,” Aerin said firmly. “It is not nonsense; it is merely unspecific.” She permitted herself a grimace at her choice of understatement. “I’ve spent much of the last three years experimenting with that half a recipe. A few months ago I finally found out ... what works.” Arlbeth’s frown had lightened, but it was still visible. “Look.” Aerin unslung the heavy cloth roll she’d hung over her shoulder and pulled out the soft pouch of her ointment. She smeared it on one hand, then the other, noticing as she did so that both hands were trembling. Quickly, that he might not stop her, she went to the fireplace and seized a burning branch from it, held it at arm’s length in one greasy yellow hand, and thrust her other hand directly into the flame that billowed out around it.

Arlbeth’s frown had disappeared. “You’ve made your point; now put the fire back into the hearth, for that is not a comfortable thing to watch.” He went back behind his table and sat down; the weary lines showed again in his face.

Читать дальше