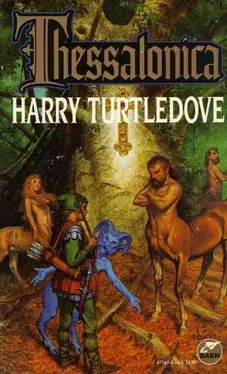

Harry Turtledove - Thessalonica

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Harry Turtledove - Thessalonica» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Thessalonica

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Thessalonica: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Thessalonica»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Thessalonica — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Thessalonica», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Eusebius’ eyes went hooded, unfathomable. George knew what that meant: the bishop was figuring out whether to He to him and, if so, what sort of he to tell. But, at last,

Eusebius answered, “Yes it is, as a matter of fact, though I’ll thank you for not spreading it broadcast through the city. I also remind you that evil is no less evil for being powerful, only more deadly.”

“I understand that,” George said--did Eusebius take him for a lackwit? Well, maybe Eusebius did.

“You did not hear of the vicious power of these demons from the Slavs you encountered today?” Eusebius asked He answered his own question: “No, of course you did not, for by your own statement you and they had no words in common.” His gaze sharpened. “Where, then, did you hear this about them?”

George abruptly wished he’d kept his mouth shut. He didn’t know whether lying to the bishop or telling him the truth was the worse choice. Eusebius had told him the truth, or at least he thought the bishop had. He decided to return the favor: “A satyr told me, the last time I was out hunting in the woods.”

Eusebius hadn’t been looking for that. His eyebrows climbed up toward his hairline, and he let out a hiss that made George wonder if he were part viper on his mother’s side. Then he crossed himself, as if the shoemaker were himself a relic of a creed outworn. When George failed either to vanish or to turn into some loathsome demon, the bishop regained control of himself. “That is a--bold admission to make,” he said, picking his words with obvious care.

“Why?” George asked stolidly. “Without the satyr, you wouldn’t have had this news, and I think it’s important, don’t you?”

“On that we do not disagree,” Eusebius said. “On a good many other matters, I suspect such a statement would be as false as any from Ananias’ lips.”

“Maybe,” George said, stolid still. “But I didn’t come here to tell you about anything else.”

Underneath that impassive shell, he was troubled. Once a bishop started worrying about--and worrying at--your theology, he generally didn’t let go till he’d made you sorry you ever crossed his path. And Eusebius, being more aggressively pious than a lot of his fellows, had a worse name for that than most.

The inspiration--if not divine, certainly convenient-- struck George. “Because you’re prefect now, Your Excellency, or pretty much prefect, anyway, I was sure you wouldn’t want any danger to come to Thessalonica.”

“Of course not,” Eusebius said at once. “Protecting the city is the most important thing I can do, the garrison being gone and the secular leaders away petitioning the Emperor Maurice.” Sure enough, George had managed to distract him, to make him think of Thessalonica rather than satyrs.

“How can we fight demons that defeat even holy priests?” the shoemaker asked, wanting to keep Eusebius’ mind away from him and on the bigger picture. That’s only proper, George thought, remembering the mosaics that made the basilica of St. Demetrius so splendid. If you look at one tessera, you don’t see anything in particular. But if you look at what all the tiles do when they’re working together. . .

He’d also chosen the right question to ask Eusebius. The bishop said, “We can--we shall--we must--do two things. First, we must reconsecrate ourselves and bring our lives into closer accord with God’s will, so that other powers will be less able to get a grip on us. And, second, we must make certain the walls of Thessalonica remain strong and the militia alert. For have you not seen how such sorceries seek to weaken not just the spiritual but also the material defenses set against them and those who make them?”

“Yes, I have seen that, Your Excellency,” George answered, surprised now in his turn: he hadn’t figured Eusebius would reckon material defenses as important is he obviously did.

The bishop said, “What else have you learned of the powers the Slavs, in their ignorance, prefer to the holy truth of God?”

He did not ask where George had learned whatever else he’d learned. The shoemaker took that as a tacit promise not to raise the issue of satyrs anymore. He didn’t mention his source again, either, replying, “I hear they have other powers nearly as strong as the wolves. I cannot really speak about that because of what I’ve seen with my own eyes, though when I was on sentry-go one night, I did see a bat, or maybe two bats, that weren’t like any natural bats I’ve spied before.”

“Are you certain of this?” Eusebius asked.

“No, Your Excellency,” George said at once. “Plenty of people must know more about bats than I do, but I can’t think of anyone who knows less. Who pays attention to bats?”

“Who, indeed?” the bishop said. “Well, God willing, perhaps we shall yet be able to keep Thessalonica from being interred in a blood-filled, barbarous sarcophagus. If this be so, you, George, shall have played no small part in the preservation of the city, thanks to this information you have brought me. I am grateful, and no doubt God is grateful as well.” He started fiddling with his pen, a sure sign he’d given George all the time he’d intended.

George rose and, after bowing to Eusebius, made his way out of the prelate’s office. As he strode up its central aisle, he paid more attention to the basilica of St. Demetrius than he was in the habit of doing. Just being inside the church dedicated to the martial saint made him feel stronger and braver than he did anywhere else in the city: more like a real soldier than a militiaman.

After walking past the ciborium and then out of the basilica, he turned back toward it and sketched a salute of the same sort as he might have given to Rufus. If St. Demetrius could extend his influence over all of Thessalonica, if he could make everyone feel stronger than without his intercession . . . that might help, if the two Slavs George had encountered outside the city were, as he feared, the harbingers of more.

But, as George walked north and mostly west back toward his shop, his home, his family, and away from the shrine, the feeling faded, until he was only himself again, and oddly diminished on account of that. He forced his shoulders to straighten and his stride to lengthen. Even without the saint s beneficent influence close by, he remained himself.

“Blood-filled, barbarous sarcophagus,” he muttered under his breath, which made a woman walking in the other direction give him a strange look and move a little farther away from him. He didn’t blame her; he would have moved away from anyone mumbling about a blood-filled sarcophagus, too.

It s Eusebius’ fault, he thought. The bishop pulled out funereal images at any excuse or none. George glanced toward the walls of Thessalonica. Surely, they would not be the walls of a stone coffin to enclose the corpse of the city.

He shook his head. “He’s got me doing it,” he said, which made someone else give him a sidelong glance.

Irene rounded on him when he walked in the door. “I thought you weren’t coming back,” she said indignantly. “I thought Eusebius wouldn’t let you come back. You told him about the satyr, didn’t you?” She didn’t wait for him to answer. “I knew you were going to tell him about the satyr. Why did you go and tell him about the satyr?”

“It was either that or tell him lies,” George answered. “Would you rather I told a holy man lies?”

“Of course I would,” Irene answered with the same certainty and lack of hesitation George used when imparting what was, with luck, wisdom to Theodore or, more rarely, Sophia. How could you be so foolish as to think otherwise? Her tone demanded.

George usually accepted such rebukes from her, because he knew he usually deserved them when he got them. Today, though, he balked. “I went to tell the bishop about the Slavs and about their demons,” he said. “It was only natural for him to ask how I knew what I knew. When he did ask me that, I didn’t see what choice I had but to tell him the truth, so he could know how seriously to take the news I was giving him.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Thessalonica»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Thessalonica» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Thessalonica» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.