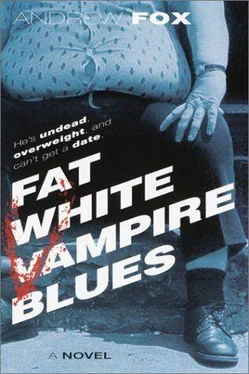

TheD word flashed through his brain.Diet. As much as he hated to think it, it wouldn’t go away. His damn knees kept reminding him. For the sake of his health, he had to lose some weight.

Jules cut off the radio on the forty-five-minute drive back to the city. He was in one foul, low-down mood. Why couldn’t pleasurable things just be pleasurable and that was that? Why did the world have to be so complicated and twisted, so that the things you loved best were the very things that were worst for you? Even from behind the closed sun visor, hidden from his sight, the newspaper clipping taunted him.NEW ORLEANS.FATTEST.CITY.IN.NATION. He wanted to crumple it up. He wanted to tear it into a hundred tiny pieces, toss them out the Caddy’s window, and watch them sink into Lake Pontchartrain. But he couldn’t make himself do it. The damn clipping would just stay in his head, anyway.

Back in the city, driving along Tulane Avenue on his way back to the French Quarter, Jules approached the imposing edifice of St. Joseph’s, the largest church in New Orleans. His mother had taken him there for Mass every Easter when he was a boy. Compared with their neighborhood parish church in the Ninth Ward, St. Joseph’s had been immense, easily the biggest building little Jules had ever set foot in. The stained-glass windows looked a thousand feet high, and he’d imagined that every Catholic in the state of Louisiana could fit inside, with room to spare for folks from Mississippi.

Tired and dejected, wanting to rest a minute, Jules pulled over to the curb in front of the church. The area had been gorgeous when he’d been young, a neighborhood of mansions to rival those on St. Charles Avenue. Now the church’s closest neighbors were a check-cashing joint, a cheap-jack furniture store, and a twenty-four-hour greasy spoon patronized mainly by housekeeping staff from the nearby LSU Medical Center. Jules hadn’t looked this long at a church in years. Back in the late 1960s, after Vatican II, Jules had satisfied his curiosity about the controversial changes by attending evening Mass at this very church. His mother had raised him right, after all; even half a century as a vampire hadn’t eradicated his upbringing, and he’d been nostalgic for his old churchgoing days. Sure enough, the switch from Latin Mass to English had made a difference for Jules. The priest’s intonations had merely caused him to be violently sick to his stomach, instead of making his skin smoke and his hair catch fire.

So why had he stopped in front of St. Joseph’s tonight? Jules listened to the hum of traffic from the nearby elevated highway as he tried to figure himself out. Was he feeling guilty about what he’d done? He rolled down his window and hocked a gob of phlegm into the street. That wasridiculous, too ridiculous a notion for him even to consider. “Everybody has to eat, don’t they?” he told himself. “Do steak lovers feel guilty about the cows? Do vegetarians get all weepy when they’re dicing carrots?Hell no! So why shouldI be different?”

Jules shifted the Caddy’s Hydramatic transmission back into drive. It had been a tiresome night; it was time to head home. He passed by Charity Hospital and the tall, modern hotels that lined both sides of Canal Street, choosing a route that would take him back through the Quarter. Almost as soon as he turned onto shadowy Decatur Street, however, he had reason to regret his choice. This hour of the night, the street was teeming with vampires. Notreal vampires, mind you. Just skinny kids with an attitude.

“Damn punk kids. Wanna-bes! The whole goddamn Quarter’s crawling with them!” he muttered darkly to himself as he steered slowly around an obstacle course of deep, jagged potholes, the ever-present legacy of the city’s having been built on swampland. Jules scowled at the black-clothed teenagers crowding the narrow, neon-lit sidewalks. Their sun-starved pallor was heightened by layers of pressed powder and liberal applications of dark eyeliner and tar-black hair dye. When local horror author Agatha Longrain had gotten hot and the vampire books and movies had begun pouring out of New Orleans, drawing hordes of vampire-crazed adolescents to the city, Jules had been able to laugh it all off. Not anymore. False vampires were everywhere-on the streets, on the television. There was even a New Orleans-based Goth-punk-Cajun band-led by popular singer Courane L’Enfant-whose vampire shtick revolved around such dubious spectacles as hovering above the concert stage suspended from a bat-wing harness and drinking the blood of a live rat.

He slowed to a crawl and watched a bone-thin boy, maybe all of seventeen, disappear into Kaldi’s, a coffee bar popular with the Goth-bohemian crowd. Jules had been able to affect that wraithlike look back in his prime.Yeah, Goth-boy, enjoy the look while you can. Spend a couple more years in the Big Easy and you ain’t gonna be wearing those size twenty-eight black jeans no more.

A loud banging noise from the front of his car startled Jules out of his musings. He immediately mashed his brakes, filling the air with asbestos dust and a loud screech even though he hadn’t been going any faster than eight miles an hour. A young, chalk-white couple were standing by the hood of his Caddy. The boy was bashing the hood with his fist.

“Hey lard-ass! Watch where you’re fuckin‘ driving! You almost fuckin’ hit us!”

Jules felt his face fill with purloined blood. He rolled down his window as fast as it would go. “The street’s for cars, asshole! Move over to the goddamn sidewalk!”

The boy kicked at the Caddy’s grille. Jules heard the sickening crunch of boot against plastic. “Fuck you!” the boy shouted. “What are you gonna do, huh? Get out of your boat and sit on me, lard-ass?”

Jules stabbed his horn with a fleshy fist. “Damn gutter punks! Goth puke-heads!” he screamed out his window. “Go home to your mamas in Baton Rouge!”

He gunned his engine and jammed his brakes simultaneously, making the Caddy jerk forward like a mechanical tyrannosaurus. The boy must’ve decided that discretion was the better part of valor, because he dragged his chalky girlfriend over to the far sidewalk, where they vanished into Kaldi’s, but not before shooting Jules a parting bird.

The car behind Jules honked annoyingly. Jules found himself without even enough strength to lean out the window and tell the offending driver to screw himself. He felt awful. His stomach had gone all acidy and his hands were shaking again. He felt as crummy as he had early in the evening, before he’d eaten anything at all. And his lousy knees were back to their throbbing.

Lard-ass.That was it. The final straw. He was going on a diet, no question about it.

Ahh… home at last.

Jules felt his stomach quiet as he turned onto good old Montegut Street. Even his knees stopped throbbing, or throbbed a little less. In his more than one hundred years on earth, this was the only neighborhood he’d ever lived in. He’d been born here, not more than half a block from the Mississippi River. The river was in his blood. Midwestern mud, fertilizer runoff, toxic discharges from chemical plants-yeah, he supposed they were in his blood, too.

Sure, the neighborhood had seen some changes. In the old days this stretch of Montegut Street between St. Claude Avenue and the river had been crowded with closely bunched houses, bustling family homes separated by alleys the width of a garbage can. Now Jules’s house was the only occupied structure left on his block. All the other homes had been abandoned, one by one, as the neighborhood had gone down over the last thirty years. Some had decayed into crack dens. Others, like the rambling three-story Victorian that once fronted the levee, had burned to the ground, victims of fires lit by vagrants on chill winter nights. None of this disturbed Jules overly much, especially since his mother hadn’t lived to see it. He liked his privacy. The old Victorian had blocked his view of the ships on the river. And besides, sometimes the crack houses furnished him with a passable meal.

Читать дальше