I looked at my self-guiding map and set out to visit the Art Museum, which had three stars. The day was cool and sunny. The town, built mostly of grey stone with red tile roofs, looked old, settled, prosperous. People went about their business paying no attention to me. The Uñiats seemed mostly to be heavy-set, white-skinned, and red-haired. All of them wore coats, long skirts, and thick boots.

I found the Art Museum in its little park and went in. The paintings were mostly of heavyset, white-skinned, red-haired women with no clothes on, though some wore boots. They were well painted, but they didn’t do much for me. I was on my way out when I got drawn into a discussion. Two people, both men I thought, though it was hard to say given the coats, skirts, and boots, stood arguing in front of a painting of a plump red-haired female wearing nothing but boots on a flowered couch.

As I passed, one of them turned to me and said, or so my trans-latomat rendered what he said, “If the figure’s a central design element in the counterplay of blocks and masses, you can’t reduce the painting to a study of indirect light on surfaces, can you?”

He, or she, asked the question so simply, directly, and urgently that I could not merely say, “Excuse me?” or shake my head and pretend to be uncomprehending. I looked again at the painting and after a moment said, “Well, not usefully, perhaps.”

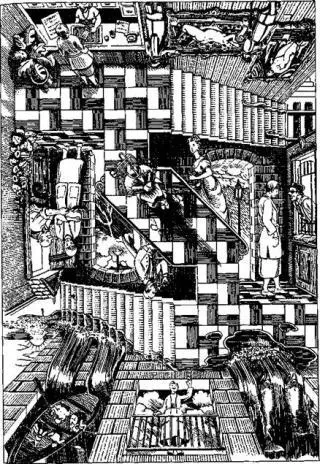

“But listen to the woodwinds,” said the other man, and I realised that the ambient music was an orchestral piece of some kind, dominated at the moment by plangent wind instruments, oboes perhaps, or bassoons in a high register. “The change of key is definitive,” the man said, a little too loudly. The person sitting behind us leaned forward and hissed, “Shh!” while a person in the row in front of us turned around and glared. Embarrassed, I sat very still throughout the rest of the piece, which was quite pretty, though the changes of key, or something of that kind—the only way I can recognise a change of key is when I cry without knowing why I am crying—gave it a certain incoherence. I was surprised when a tenor, or possibly a contralto, whom I had not previously noticed, stood up and began to sing the main theme in a powerful voice, ending on a long high note to wild applause from the audience in the big auditorium. They shouted and clapped and demanded an encore. But a gust of wind blowing in from the high hills to the west across the village square made all the trees shiver and bow, and looking up at the clouds streaming overhead I realised a storm was imminent. The clouds darkened from moment to moment, another great blast of wind struck, whirling up dust and leaves and litter, and I thought I’d better put on my raincoat. But I had checked it at the cloakroom in the Art Museum. My trans-latomat was clipped to my jacket lapel, but the self-guiding map had been in my raincoat pocket. I went to the desk in the tiny station building and asked when the next train left, and the one-eyed man behind the narrow iron grating said, “We do not have trains now.”

I turned to see the empty tracks stretching away under the vast arched roof of the station, track after track, each with its number and its gate. Here and there was a luggage cart, and a single distant passenger straying idly down a long platform, but no trains. “I need my raincoat,” I said, in a kind of panic.

“Try Lost and Found,” the one-eyed clerk said, and busied himself with forms and schedules. I walked across the great hollow space of the station towards the entrance. Beyond a restaurant and a coffee bar I found the Lost and Found. I went into it and said, “I checked my raincoat at the Art Museum, but I have lost the Art Museum.”

The statuesque red-haired woman at the counter said, “Wait a minute” in a bored voice, rummaged a bit, and shoved a map across the counter. “There,” she said, pointing at a square with a white, plump, red-nailed finger. “That’s the Art Museum.”

“But I don’t know where I am. Where this is. This village.”

“Here,” she said, pointing out another square on the map. It seemed to be ten or twelve streets from the Art Museum. “Better go while the conformation lasts. Stormy today.”

“Can I take the map?” I asked pitifully. She nodded.

I went out into the city streets, so mistrustful that I walked with short steps, as if the pavement might turn into an abyss before my feet, or a cliff face rise up before me, or the street crossing turn into the deck of a ship at sea. Nothing happened. The wide, level streets of the city crossed each other at regular intervals, treeless, quiet. The electric buses and taxis made little noise, and there were no private cars. I walked on. The map took me right back to the Art Museum, which I thought had had green-and-white marble steps instead of black slate ones, but other things about it were as I remembered. In general, I have a poor memory. I went in and asked at the cloakroom for my raincoat. While the black-haired, silver-eyed girl with thin black lips was looking for it, I wondered why I had asked, at the train station, when the next train left. Where had I thought I was going? All I had wanted was my coat at the Art Museum. If there had been a train, would I have taken it? Where would I have got off?

As soon as I had my coat, I hurried back through the steep, cobbled streets lined with charming balconied houses and crowded with the slender, almost skeletal, black-lipped people of Uñi, towards the Interplanary Hotel to demand an explanation. It was probably something in the air, I thought, as the fog thickened, hiding the mountains above the town and the peaked roofs of the houses on the hills. Maybe people on Uсi smoked something hallucinatory, or there was some pollen or something in the air or in the fog that affected the mind, confused the senses, or—a nasty thought—deleted stretches of memory, so that things seemed to happen without sequence and you couldn’t remember how you’d got where you were or what had happened in between. And having a poor memory, I might not be sure whether I had lost parts of it or not. It was like dreaming in some respects, but I was certainly not dreaming, only confused and increasingly alarmed, so that despite the damp cold I didn’t stop to put on my raincoat, but hurried shivering onward through the forest.

I smelled wood smoke, sweet and sharp in the wet air, and presently saw a gleam of light through the twilight mist that gathered almost palpable among the trees. A woodcutter’s hut stood just off the path, a shadowy bit of kitchen garden beside it, the red-gold glow of firelight in the low, small-paned window, smoke drifting up from the chimney, a lonesome, homely sight. I knocked. After a minute an old man opened the door. He was bald, and had an enormous wen or wart on his nose and a frying pan in his hand, in which sausages were sizzling cheerily. “You can have three wishes,” he said.

“I wish to find the Interplanary Hotel,” I said.

“That is the wish you cannot have,” the old man said. “Don’t you want to wish that the sausages were growing out of the end of my nose?”

After a brief pause for thought, I said, “No.”

“So, what do you wish for, besides the way to the Interplanary Hotel?”

I thought again. I said, “When I was twelve or thirteen, I used to plan what I’d wish for if they gave me three wishes. I thought I’d wish, ( wish that having lived well to the age of eighty-five and having written some very good books, I may die quietly, knowing that all the people I love are happy and in good health, I knew that this was a stupid, disgusting wish. Pragmatic. Selfish. A coward’s wish. I knew it wasn’t fair. They would never allow it to be one of my three wishes. Besides, having wished it, what would I do with the other two wishes? So then I’d think, with the other two I could wish that everybody in the world was happier, or that they’d stop fighting wars, or that they’d wake up tomorrow morning feeling really good and be kind to everybody else all day, no, all year, no, forever, but then I’d realise I didn’t really believe in any of these wishes as anything but wishes. So long as they were wishes they were fine, even useful, but they couldn’t go any further than being wishes. By nothing I do can I attain a goal beyond my reach, as King Yudhishthira said when he found heaven wasn’t all he’d hoped for. There are gates the bravest horse can’t jump. If wishes were horses, I’d have a whole herd of them, roan and buckskin, lovely wild horses, never bridled, never broken, galloping over the plains past red mesas and blue mountains. But cowards ride rocking horses made of wood with painted eyes, and back and forth they go, back and forth in one place on the playroom floor, back and forth, and all the plains and mesas and mountains are only in the rider’s eyes. So never mind about the wishes. Give me a sausage, please.”

Читать дальше