I am certain this terrible poverty dates from the age of the ruins. Their ancestors, with all the resources of science and all the best intentions, robbed them blind. Our world is full of diseases, enemies, waste, and danger, those ancestors said— hostile microbes and viruses infecting us, noxious weeds growing thick about us while we starve, useless animals that carry plagues and poisons and compete with us for air and food and water. This world is too hard for human beings to live in, too hard for our children, they said, but we know how to make it easy.

So they did. They eliminated everything that was not useful. They took a great complex pattern and simplified it to perfection. A nursery room safe for the children. A theme park where people have nothing to do but enjoy themselves.

But the Nna Mmoy outwitted their ancestors, at least in part. They’ve made the pattern back into something endlessly complicated, infinitely rich, and without any rational use. They do it with words.

They don’t have any representative arts. They decorate their pottery and whatever else they make only with their beautiful writing. The only way they imitate the world is by putting words together: that is, by letting words interrelate in a fertile, ever-changing complexity to form shapes and patterns that have never existed before, beautiful forms that exist briefly and create and give way to other forms. Their language is their own exuberant, endlessly proliferating ecology. All the jungle they have, all the wilderness, is their poetry.

As I said, the pictures in my magazine interested them, the pictures of animals. They gazed at them with what seemed to me an uncomprehending wistfulness. I told them the names, pointing out the word written as I spoke it. And they’d repeat: Pan dhedh. Kon dodh. Ma na tii.

Those were the only words of my language they ever listened to, recognising that they had meaning.

I suppose they understood as much from those words as I did from the syllables of their language that I learned: very little, and probably all wrong.

I wandered around the ancient ruins near the village sometimes. I found a wall that had been revealed when one of the villages used the place as a rock quarry. There was a carving, a bas-relief, worn away by the ages, but as I studied it I began to see what it was: a procession of people, and there were other creatures in the procession. It was hard to make out what they were. Animals, certainly. Some were four-legged. One had great horns or wings. They might have been real animals or imaginary, or figures of animal gods. I tried to ask the teacher about them, but she just said, “Nen, nen.”

From the unpublished Voyages to Qoq, Rehik, and Djg, by Thomas Atall, with the kind permission of the author

THE PLANE OF QOQ is unusual in having two rational, or more or less rational, species.

The Daqo are stocky, greenish-tan-colored humanoids. The Aq are taller and a little greener than the Daqo. The two species, though diverged from a common simioid ancestor, cannot interbreed.

Something over four thousand years ago the Daqo had what the Planar Encyclopedia refers to as an EEPT: a period of explosive expansion of population and technology.

Before it, the two species had seldom come in contact. The Aq inhabited the southern continent, the Daqo were in the northern hemisphere. The Daqo population escalated, spreading out over the three landmasses of the northern hemisphere and then to the south. As they conquered their world, they incidentally conquered the Aq.

The Daqo attempted to use the Aq as slaves for domestic or factory work but failed. It seems the Aq, though unaggres-sive, do not take orders. During the height of the EEPT the most expansive Daqo nations pursued a policy of slaughtering the “primitive” and “unteachable” Aq in the name of progress. Settlers of the equatorial zone pushed the remnant Aq populations farther south yet, into the deserts and the barely habitable canebrakes of the coast.

All species on Qoq, except a few pests and the insuperable and indifferent bacteria, suffered badly during and after the Daqo EEPT. In the final ecocatastrophe, the Daqo population dropped by four billion in four decades. The species has survived, living on a modest scale, vastly reduced in numbers and more interested in survival than dominion.

As for the Aq, probably very few, perhaps only hundreds, survived the rapid destruction and final ruin of the planet’s life web.

Descent from this limited genetic source may help explain the prevalence of certain traits among the Aq, but the cultural expression of these tendencies is inexplicable in its uniformity. We don’t know much about what they were like before the crash, but their reputed refusal to carry out the other species’ orders suggests that they were already working, as it were, under orders of their own.

There are now about two million Daqo, mostly on the coasts of the south and the northwest continents. They live in small cities, towns, and farms and carry on agriculture and commerce; their technology is efficient but modest, limited both by the exhaustion of their world’s resources and by strict religious sanctions.

There are probably fifteen or twenty thousand Aq, all on the southern continent. They live as gatherers and fishers, with some limited, casual agriculture. The only one of their domesticated animals to survive the die-offs is the boos, a clever creature descended from pack-hunting carnivores. The Aq hunted with boos when there were animals to hunt. Since the crash, they use boos to carry or haul light loads, as companions, and in hard times as food.

Aq villages are movable; from time immemorial their houses have been fabric domes stretched on a frame of light poles or canes, easy to set up, dismantle, and transport. The tall cane which grows in the swampy lakes of the desert and all along the coasts of the equatorial zone of the southern continent is their staple; they gather the young shoots for food, spin and weave the fiber into cloth, and make rope, baskets, and tools from the stems. When they have used up all the cane in a region, they pick up the village and move on. The cane plants regenerate from the root system in a few years.

The Aq have kept pretty much to the desert-and-canebrake habitat enforced upon them by the Daqo in earlier millennia. Some, however, camp around outside Daqo towns and engage in a little barter and filching. The Daqo trade with them for their fine canvas and baskets, and tolerate their thievery to a surprising degree.

Indeed the Daqo attitude to the Aq is hard to define. Wariness is part of it; a kind of unease that is not suspicion or distrust; a watchfulness that, surprisingly, stops short of animosity or contempt, and may even become conciliating.

It is even harder to say what the Aq think of the Daqo. The two populations communicate in a pidgin or jargon containing elements from both languages, but it appears that no individual ever learns the other species’ language. The two species seem to have settled on coexistence without relationship. They have nothing to do with each other except for these occasional, slightly abrasive contacts at the edges of southern Daqo settlements—and a limited, very strange collaboration having to do with what I can only call the specific obsession of the Aq.

I am not comfortable with the phrase “specific obsession,” but “cultural instinct” is worse.

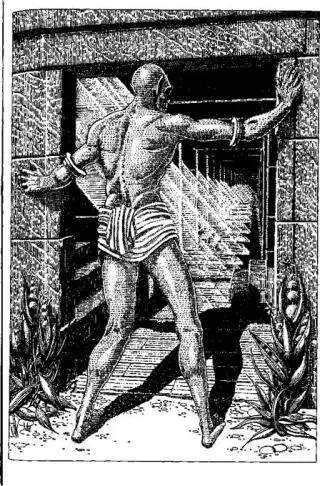

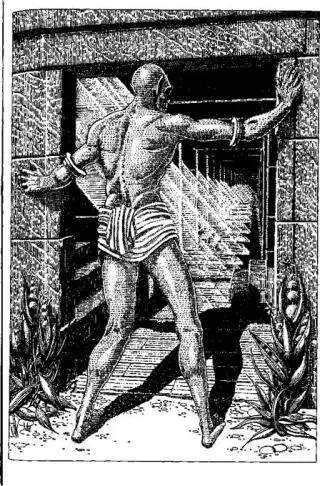

At about two and a half or three years old, Aq babies begin building. Whatever comes into their little greeny-bronze hands that can possibly serve as a block or brick they pile up into “houses.” The Aq use the same word for these miniature structures as for the fragile cane-and-canvas domes they live in, but there is no resemblance except that both are roofed enclosures with a door. The children’s “houses” are rectangular, flat-roofed, and always made of solid, heavy materials. They are not imitations of Daqo houses, or only at a very great remove, since most of these children have never been to a Daqo town, never seen a Daqo building.

Читать дальше