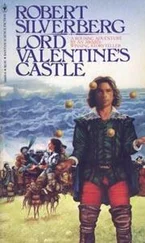

But also within him there resounded the music of the water-king Maazmoorn. He had been so close, this time, to the ultimate breakthrough, to the true contact with that inconceivably gigantic creature of the sea. Now—tonight—

Carabella remained awake for a while to talk. That ancient Ghayrog woman haunted her, too, and she dwelled almost obsessively on the power of Aximaan Threysz’s words, the eerie compelling force of her sightless eyes, the mysteries of her prophecy. Then finally she kissed Valentine lightly on the lips and burrowed down into the darkness of the enormous bed they shared.

He waited a few endless minutes. Then he took forth the tooth of the sea dragon.

— Maazmoorn?

He held the tooth so tightly its edges dug deep into the flesh of his hand. Urgently he centered all the power of his mind on the bridging of the gulf of thousands of miles between Prestimion Vale and the waters—where? At the Pole?—where the sea-king lay hidden.

— Maazmoorn?

— I hear you, land brother, Valentine-brother, king-brother.

At last!

— You know who I am?

— I know you. I knew your father. I knew many before you.

— You spoke with them?

— No. You are the first for that. But I knew them. They did not know me, but I knew them. I have lived many circlings of the ocean, Valentine-brother. And I have watched all that has occurred upon the land.

— You know what is occurring now?

— I know.

— We are being destroyed. And you are a party to our destruction.

—No.

— You guide the Piurivar rebels in their war against us. We know that. They worship you as gods, and you teach them how to ruin us.

—No, Valentine-brother.

— I know they worship you.

— Yes, that they do, for we are gods. But we do not support them in their rebellion. We give them only what we would give anyone who comes to us for nourishment, but it is not our purpose to see you driven from the world.

— Surely you must hate us!

— No, Valentine-brother.

— We hunt you. We kill you. We eat your flesh and drink your blood and use your bones for trinkets.

— Yes, that is true. But why should we hate you, Valentine-brother? Why?

Valentine did not for the moment reply. He lay cold and trembling with awe beside the sleeping Carabella, pondering all that he had heard, the calm admission by the water-king that the dragons were gods—what could that mean?—and the denial of complicity in the rebellion, and now this astounding insistence that the dragons bore the Majipoori folk no anger for all that had been committed against them. It was too much all at once, a turbulent inrush of knowledge where before there had been only the sound of bells and a sense of a distant looming presence.

— Are you incapable of anger, then, Maazmoorn?

— We understand anger.

— But do not feel it?

— Anger is beside the point, Valentine-brother. What your hunters do to us is a natural thing. It is a part of life; it is an aspect of That Which Is. As am I, as are you. We give praise to That Which Is in all its manifestations. You slay us as we pass the coast of what you call Zimroel, and you make your uses of us; sometimes we slay you in your ships, if it seems to be what must be done at that moment, and so we make our uses of you; and all that is That Which Is. Once the Piurivar folk slew some of us, in their stone city that is now dead, and they thought they were committing a monstrous crime, and to atone for that crime they destroyed their own city. But they did not understand. None of you land-children understand. All is merely That Which Is.

— And if we resist now, when the Piurivar folk hurl chaos at us? Are we wrong to resist? Must we calmly accept our doom, because that too is That Which Is?

— Your resistance is also That Which Is, Valentine-brother.

— Then your philosophy makes no sense to me, Maazmoorn.

— It does not have to, Valentine-brother. But that too is That Which Is.

Valentine was silent once again, for an even longer time than before, but he took care to maintain the contact.

Then he said:

— I want this time of destruction to end. I mean to preserve the thing that we of Majipoor have understood as That Which Is.

— Of course you do.

— I want you to help me.

“We have captured a Shapeshifter, my lord,” Alsimir said, “who claims he bears an urgent message for you, and you alone.”

Hissune frowned. “A spy, do you think?”

“Very likely, my lord.”

“Or even an assassin.”

“That possibility must never be overlooked, of course. But I think that is not why he is here. I know that he is a Shapeshifter, my lord, and our judgments are all risky ones, but nevertheless: I was among those who interrogated him. He seems sincere. Seems.”

“Shapeshifter sincerity!” said Hissune, laughing. “They sent a spy to travel in Lord Valentine’s entourage, did they not?”

“So have I been told. What shall I do with him, then?”

“Bring him to me, I suppose.”

“And if he plans some Shapeshifter trick?”

“Then we will have to move faster than he does, Alsimir. But bring him here.”

There were risks, Hissune knew. But one could not simply turn away someone who maintains he is a messenger from the enemy, or put him to death out of hand on mere suspicion of treachery. And to himself he confessed it would be an interesting diversion to lay eyes on a Metamorph at last, after so many weeks of tramping through this sodden jungle. In all this time they had not encountered one: not one.

His camp lay just at the edge, of a grove of giant dwikka-trees, somewhere along Piurifayne’s eastern border not far from the banks of the River Steiche. The dwikkas were impressive indeed—great astounding things with trunks as wide as a large house, and bark of a blazing bright red hue riven by immense deep cracks, and leaves so broad that one of them could keep twenty men dry in a soaking downpour, and colossal rough-skinned fruits as big around as a floater, with an intoxicating pulp within. But botanical wonders alone were small recompense for the dreariness of this interminable forced march in the Metamorph rain-forest. The rain was constant; mildew and rot afflicted everything, including, Hissune sometimes thought, one’s brain; and although the army now was deployed along a line more than a hundred miles in length, and the secondary Metamorph city of Avendroyne was supposedly close by the midpoint of that line, they had seen no cities, no signs of former cities, no traces of evacuation routes, and no Metamorphs at all. It was as if they were mythological beings, and this jungle were uninhabited.

Divvis, Hissune knew, was having the same difficulty over on the far side of Piurifayne. The Metamorphs were not numerous and their cities appeared to be portable. They must flit from place to place like the filmy-winged insects of the night. Or else they disguised themselves as trees and bushes and stood silently by, choking down their laughter, as the armies of the Coronal marched past them. These great dwikkas, for all I know, might be Metamorph scouts, thought Hissune. Let us speak with the spy, or messenger, or assassin, or whatever he may be: we may learn something from him, or at the very least we may be entertained by him.

Alsimir returned in moments with the prisoner, who was under heavy guard.

He was, like those few Piurivars whom Hissune had seen before, a strangely disturbing-looking figure, extremely tall, slender to the point of frailness, naked but for a strip of leather about his loins. His skin and the thin rubbery strands of his hair were an odd pale greenish color, and his face was almost devoid of features, the lips mere slits, the nose only a bump, the eyes slanted sharply and barely visible beneath the lids. He seemed uneasy, and not particularly dangerous. All the same, Hissune wished he had someone with the gift of seeing into minds about him now, a Deliamber or a Tisana or Valentine himself, to whom the secrets of others seemed often to be no secrets at all. This Metamorph might yet have some disagreeable surprise in mind.

Читать дальше