“No.” She fought the urge to laugh in despair. “I killed him.”

For a moment, he merely gazed at her, uncomprehending. “The … Sunderer?”

“Yes,” she whispered. “The Shaper.”

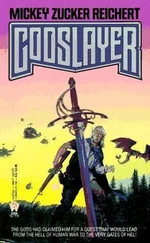

His Men did speak, then, relating what she had told them. Behind them, others emerged from the depths of Darkhaven, escorting Vorax’s handmaids and an unarmed horde of weeping, babbling madlings. Aracus listened gravely to his Borderguard. “Get torches. Find the lad and his uncle,” he said to them. “And Godslayer; Godslayer, above all. It lies in the possession of the Misbegotten, and he cannot have gotten far. Search every nook and cranny. He will be found.” He turned back to Cerelinde. “Ah, love!” he said, his voice breaking. “Your courage shames us all.”

Cerelinde shook her head and looked away, remembering the way Godslayer had sunk into Satoris’ unresisting flesh. “I did only what I believed was needful.”

Aracus took her hand in his gauntleted fingers. “We have paid a terrible price, all of us,” he said gently. “But we have won a great victory, my Lady.”

“Yes,” she said. “I know.”

She yearned to find comfort in his touch, in that quickening mortal ardor that burned so briefly and so bright. There was none. It had been the Gift of Satoris Third-Born, and she had slain him.

He had spoken the truth. And she had become the thing that she despised.

“Come,” Aracus said. “Let us seek Malthus’ counsel.”

He led her across the courtyard, filled with milling warriors and dying Fjeltroll. They died hard, it seemed. A few of them looked up from where they lay, weltering in their own gore, and met her eyes without fear. They had seemed so terrifying, once. It was no longer true.

Malthus was kneeling, his robes trailing in puddles of blood. He straightened at her approach. “Lady Cerelinde,” he said in his deep voice. “I mourn the losses of the Rivenlost this day.”

“I thank you, Wise Counselor.” The words caught in her throat, choking her. She had seen that which his keeling body had hidden. “Ah, Haomane!”

“Fear not, Lady.” It was a strange woman who spoke. In one hand, she held a mighty bow wrought of horn. Though her face was strained with grief, her voice was implacable. “Tanaros Kingslayer is no more.”

Cerelinde nodded, not trusting her voice.

Though half a dozen arrows bristled from his body, Tanaros looked peaceful in death. His unseeing eyes were open, fixed on nothing. A slight smile curved his lips. His limbs were loose, the taut sinews unstrung at last, the strong hands slack and empty. A smear of blood was across his brow, half-hidden by an errant lock of hair.

The scent of vulnus-blossom haunted her.

We hold within ourselves the Gifts of all the Seven Shapers and the ability to Shape a world of our choosing … .

Cerelinde shuddered.

She could not allow herself to weep for his death; not here. Perhaps not ever. Lifting her head, she gazed at Aracus. He was a choice she had made. He returned her gaze, his storm-blue eyes somber. There would be no gloating over this victory. His men had told her of the losses they had endured on the battlefield, of Blaise Caveros and Lord Ingolin the Wise, and many countless others.

She saw the future they would shape together stretching out before her. Although the shadow of loss and sorrow would lay over it, there would be times of joy, too. For the brief time that was alotted them together, they would find healing in one another, and in the challenge of bringing their races together in harmony.

There would be fear, for it was in her heart that neither Ushahin nor Godslayer would be found on the premises of Darkhaven. Haomane’s Prophecy had been fulfilled to the letter, and yet it was not. Without Godslayer, the Souma could not be made whole, and the world’s Sundering undone. The Six Shapers would remain on Torath, apart, and Ushahin would be an enemy to Haomane’s Allies; less terrible than Satoris Banewreaker, for even with a Shard of the Souma, he would not wield a Shaper’s power, capable of commanding the loyalty of an entire race. More terrible, for he did not have a Shaper’s pride and the twisted sense of honor that went with it.

There would be hope, for courage and will had triumphed over great odds on this day, and what was done once might be done again.

There would be love. Of that, she did not doubt. She was the Lady of the Ellylon, and she did not love lightly; nor did Aracus. They would be steadfast and true. They would rule over Urulat with wisdom and compassion.

And yet there would be doubt, born out of her long captivity in Darkhaven.

Shouting came from the far side of the courtyard. More Borderguardsmen were emerging from Darkhaven, carrying two limp figures. The Bearer and his uncle had been found and rescued. One stirred. Not the boy, who lay motionless.

“Aracus.” Malthus touched his arm. “Forgive me, for I know your weariness is great. Yet it may be that the Soumanië can aid him.”

“Aye.” With an effort, Aracus gathered himself. “Guide me, Counselor.”

In the midst of slaughter and carnage, Cerelinde watched them tend to the stricken Yarru, their heads bowed in concentration. The young Bearer was gaunt and frail, as though his travail had pared him down to the essence.

She tried to pray and could not, finding herself wondering, instead, if this victory was worth its cost. She longed to weep, but her eyes remained dry. She watched as the Bearer drew in a breath of air, sudden and gasping, his narrow chest heaving. She longed to feel joy, but felt only pity at the harshness with which Haomane used his chosen tools. She listened to the shouts of Men, carrying out the remainder of their futile search, and to the horns of the Rivenlost, declaring victory in bittersweet tones.

And she knew, with the absolute certainty with which she had once believed in Haomane’s unfailing wisdom and goodness, that no matter what else the future held, in a still, silent place in her heart that she would never share—not with Aracus, nor Malthus the Counselor, nor her own kinfolk—she would spend the remainder of her days seeing the outstretched hand of Satoris Third-Born before her, feeling the dagger sink into his breast, and hearing his anguished death-cry echoing in her ears.

Wondering why he had let her take his life; and why Tanaros had spared hers. Wondering if there was another scion of Elterrion’s line upon the face of Urulat. Wondering if her mother had prayed to Satoris on her deathbed.

Wondering why the Six Shapers did not dare leave Torath, and whether a world in which Satoris prevailed would truly have been worse than one over which Haomane ruled, an absent father to his Children.

Wondering where lies ended and truth began.

Wondering if she had chosen wisely at the crossroads she had faced.

Wondering, and never daring to know.

What might have been?

A shadow passed through the Defile, disturbing the shroud of webbing that hung from the Weavers’ Gulch in tattered veils. The little grey weavers chittered in dismay, scuttling furiously, setting about their endless work of rebuilding and repair.

No one else noticed.

Ushahin-who-walks-between-dusk-and-dawn rode the pathways between one thing and another; between waking and dreaming, between life and death, between the races of Lesser Shapers, between a dying Age and one being born.

He rode a blood-bay stallion, its coat the hue of drying gore, its mane and tail as black as the spaces between the stars. Lashed to his saddle was a leather case that contained a broken Helm, its empty eye-sockets gazing onto darkness.

And at his belt he bore a dagger wrought from a single Shard of the Souma, the Eye in the Brow of Uru-Alat. It was red, pulsing with its own inner light, and it would have betrayed his presence had he not wrapped it in shadow, in a cloak of the vague ambiguities that lay between victory and defeat, between pride and humility, between right and wrong.

Читать дальше