She gazed at him. “What will you do?”

“What do you think?” He smiled wearily. “I will die, Cerelinde. I will die with whatever honor is left to me.” He moved away, pointing toward the right-hand door with the tip of his sword. “Now go.”

“Tanaros.” She took a step toward him. “Please …”

“Go!” he shouted. “Before I change my mind!”

The Lady of the Ellylon bowed her head. “So be it.”

Ushahin watched her leave.

As much as he despised her, the Chamber was darker for her absence. It had been a place of power, once. For a thousand years, it had been no less. Now it was only a room, an empty room with a scorched hole in the floor and an echo of loss haunting its corners, a faint reek of coppery-sweet blood in the air.

“What now, cousin?” he asked Tanaros.

Tanaros gazed at his hands, still gripping his sword; strong and capable, stained with ichor. “It was his Lordship’s will,” he murmured. “He entrusted me with his honor.”

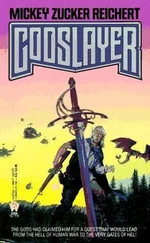

“So you say.” Ushahin thrust Godslayer into his belt and stooped to retrieve the case that held the sundered Helm of Shadows. “Of a surety, he entrusted me with the future, and I would fain see his will done.”

“Aye.” Tanaros gathered himself. “Haomane’s Allies are at the Gate?”

Ushahin nodded. “They are. I bid the Havenguard to hold it.”

“Good.” The General touched a pouch that hung from his swordbelt. His haunted gaze focused on Ushahin. “Dream-spinner. You can pass between places, hidden from the eyes of mortal Men. I know, I have ridden with you. Can you use such arts to yet escape from Haomane’s Allies?”

“Perhaps.” Ushahin hesitated. “It will not be easy. Not with the Host of the Rivenlost at our Gate, the Soumanië at work, and Malthus the Counselor among them.”

Tanaros smiled grimly. “I mean to provide them with a distraction.”

“It will have to be swift. If the Lady escapes to tell her tale, they will spare no effort to capture Godslayer.” Unaccountably, Ushahin’s throat ached. His words came unbidden, painful and accusatory. “Why did you do it, Tanaros? Why?”

The delicate traceries of marrow-fire lingering in the stone walls were growing dim. The hollows of Tanaros’ eyes were filled with shadows. “What would you have me answer? That I betrayed his Lordship in the end?”

“Perhaps.” Ushahin swallowed against the tightness in his throat. “For it seems to me you did love her, cousin.”

“Does it?” In the gloaming light, Tanaros laughed softly. “In some other life, it seems to me I might have. In this one, it was not to be. And yet, I could not kill her.” He shook his head. “Was it strength or weakness that stayed my hand? I do not know, any more than I know why his Lordship allowed her to take his life. In the end, I fear it will fall to you to answer.”

A silence followed his words. Ushahin felt them sink into his awareness and realized for the first time the enormity of the burden that had settled on his crooked shoulders. He thought of the weavers in the gulch, spinning their endless patterns; of Calanthrag in her swamp with the vastness of time behind her slitted eyes. He laid his hand upon Godslayer’s rough hilt, feeling the pulse of its power; the power of the Souma itself, capable of Shaping the world. The immensity of it humbled him, and his bitterness gave way to grief and a strange tenderness. “Ah, cousin! I will try to be worthy of it.”

“So you shall.” Tanaros regarded him affection and regret. “His Lordship bid me teach you to hold a blade. Even then, he must have suspected. I do not envy you the task, Dreamspinner. And yet, it is fitting. In some ways, you were always the strongest of the Three. You are the thing Haomane’s Allies feared the most, the shadow of things to come.” Switching his sword to his left hand, he extended his right. “We waste time we cannot afford. Will you not bid me farewell?”

Here at the end, they understood one another at last.

“I will miss you,” Ushahin said quietly, clasping Tanaros’ hand. “For all the days of my life, howsoever long it may be.”

Tanaros nodded. “May it be long, cousin.”

There was nothing more to be said. Ushahin turned away, his head averted. At the top of the winding stair, he paused and raised his hand in farewell; his right hand, strong and shapely.

And then he passed through the left-hand door.

Tanaros stood alone in the darkening Chamber, breathing slow and deep. He returned the black sword to his right hand, his fingers curving around its familiar hilt. It throbbed in his grip. His blood, his Lordship’s blood. The madlings had always revered it. Tempered in the marrow-fire, quenched in ichor. It was not finished, not yet.

Death is a coin to be spent wisely .

Vorax had been fond of saying that. How like the Staccian to measure death in terms of wealth! And yet there was truth in the words.

Tanaros meant to spend his wisely.

It would buy time for Ushahin to make his escape; precious time in which the attention of Haomane’s Allies was focused on battle. And it would buy vengeance for those who had fallen. He had spared Cerelinde’s life. He did not intend to do the same for those who took arms against him.

There were no innocents on the battlefield. They would pay for the deaths of those he had loved. Tanaros would exact full measure for his coin.

He touched the pouch that hung from his swordbelt, feeling the reassuring shape of Hyrgolf’s rhios within it.

The middle door was waiting.

It gave easily to his push. He strode through it and into the darkness beyond. These were his passageways, straight and true, leading to the forefront of Darkhaven. Tanaros did not need to see to know the way. “Vorax. Speros. Hyrgolf,” he murmured as he went, speaking their names like a litany.

The passageway was long and winding, and the marrow-fire that lit it grew dim, so dim that she had to feel her way by touch. But Tanaros had not lied; the passage was empty. Neither madlings nor Fjel traversed it. At the end, there was a single door.

Cerelinde fumbled for the handle and found it began to whisper a prayer to Haomane and found that the words would not come. The image of Satoris Banewreaker hung before her, stopping her tongue.

Still, the handle turned.

Golden lamplight spilled into the passage. The door opened onto palatial quarters filled with glittering treasure. Clearly, these were Vorax’s quarters, unlike any other portion of Darkhaven. Within, three mortal women leapt to their feet, staring. They were fair-haired northerners, young and comely after the fashion of Arahila’s Children.

“Vas leggis?” one asked, bewildered. And then, slowly, in the common tongue: “Who are you? What happens? Where is Lord Vorax?”

Tanaros had not lied.

It made her want to weep, but the Ellylon could not weep for their own sorrows. “Lord Vorax is no more,” Cerelinde said gently, entering the room. “And the reign of the Sunderer has ended in Urulat. I am Cerelinde of the House of Elterrion.”

“ Ellyl!” The youngest turned pale. She spoke to the others in Staccian, then turned to Cerelinde. “He is dead? It is ended?”

“Yes,” she said. “I am sorry.”

And strangely, the words were true. Even more strangely, the three women were weeping. She did not know for whom they wept, Satoris Banewreaker or Vorax the Glutton. She had not imagined anyone could weep for either.

The oldest of the three dried her eyes on the hem of her mantle. “What is to become of us?”

There was a throne in the center of the room, a massive ironwood seat carved in the shape of a roaring bear. Cerelinde sank wearily into it. “Haomane’s Allies will find us,” she said. “Be not afraid. They will show mercy. Whatever you have done here, Arahila the Fair will forgive it.”

Читать дальше