It fell to him, this hardest of tasks. Somehow it seemed he had always known it would. When all was said and done, in some ways his lot had always been the hardest. He had seen the pattern closing upon them. He had spoken with Calanthrag the Eldest. It was fitting. Kneeling on the flagstones, Ushahin leaned close, the ends of his moon-pale hair trailing in pools of black ichor.

“What is your will, my Lord?” he asked.

The Shaper’s lips parted. A terrible clarity was in his eyes, dark and sane, filled with knowledge and compassion. “Take it,” he breathed in reply, his words almost inaudible. “And make an end. The beginning falls to you, Dreamspinner. I give you my blessing.”

Ushahin’s shoulders shook. “Are you certain?”

The Shaper’s eyes closed. “Seek the Delta. You know the way.”

With a curse, Ushahin raised his right hand. It had been Shaped for this task. It was strong and steady. He placed it on the Shard’s crude knob of a hilt. Red light pulsed, shining between his fingers, illuminating his flesh.

It held the power to Shape the world anew, and he did not want it.

Even so, it was his.

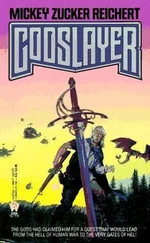

“Farewell, my Lord,” Ushahin whispered, and withdrew Godslayer.

Darkness seethed through the Chamber. The Shaper’s form dwindled, vanishing as its essence coalesced slowly into shadow, into smoke, into a drift of obsidian ash. There was no outcry, no trembling of the earth, only a stirring in the air like a long-held sigh released and a profound sense of passage, as though between the space of one heartbeat and the next, the very foundation of existence had shifted.

Quietly, uneventfully, the world was forever changed.

Ushahin climbed to his feet, holding Godslayer. “Your turn, cousin,” he said, hoarse and weary.

Cerelinde wept at the Shaper’s passing.

It did not matter, in the end, who drew forth the dagger. She had killed him. He had stood before her, unarmed, and reached out his hand. She had planted Godslayer in his breast. And Satoris Third-Born had known she would do it. He had allowed it.

She did not understand.

She would never understand.

She watched as Ushahin rose to his feet, uttering his weary words. She saw Tanaros swallow and touch the raised circle of his brand beneath his stained, padded undertunic. Hoisting his black sword, he walked slowly toward her. Standing beneath the shadow of his blade, she made no effort to flee, her tears forging a broad, shining swath down her fair cheeks.

Their eyes met, and his were as haunted as hers. He, too, had sunk a blade into unresisting flesh. He had shed the blood of those he loved, those who had betrayed him. He understood the cost of what she had done.

“I’m sorry,” he said to her. “I’m sorry, Cerelinde.”

“I know.” She gazed at him beneath the black blade’s shadow. “Ah, Tanaros! I did only what I believed was needful.”

“I know,” Tanaros said somberly. “As must I.”

“It won’t matter in the end.” She gave a despairing laugh. “There’s another, you know. His Lordship told me as much. Elterrion had a second daughter, gotten of an illicit union. So he said to me. ‘Somewhere among the Rivenlost, your line continues.’”

Tanaros paused. “And you believed?”

“No,” Cerelinde whispered. “Such things happen seldom, so seldom, among the Ellylon. And yet it was his Gift, when he had one, to know such things.” She shuddered, a shudder as delicate and profound as that of a mortexigus flower shedding its pollen. “I no longer know what to believe. He said that my mother prayed to him ere she died at my birth. Do you believe it was true, Tanaros?”

“Aye,” he said softly. “I do, Cerelinde.”

Ushahin’s voice came, harsh and impatient. “Have done with it, cousin!”

Tanaros shifted his grip on the black sword’s hilt. “The madling was right,” he murmured. “She told me you would break all of our hearts, Lady.” He spoke her name one last time, the word catching in his throat. “Cerelinde.”

She nodded once, then closed her eyes. Whatever else was true, here at the end, she knew that the world was not as it had seemed. Cerelinde lifted her chin, exposing her throat. “Make it swift,” she said, her voice breaking. “Please.”

Tanaros’ upraised arms trembled. His palms were slick with sweat, stinging from the myriad cuts and scrapes he had incurred in his climbing. He was tired, very tired, and it hurt to look at her.

Elsewhere in Darkhaven, there were sounds; shouting. His Lordship was dead and the enemy was at the gates.

A blue vein pulsed beneath the fair skin of Cerelinde’s outstretched throat.

He remembered the feel of his wife’s throat beneath his hands, and the bewildered expression on Roscus’ face when he ran him through. He remembered the light fading in the face of Ingolin the Wise, Lord of the Rivenlost. He remembered the Bearer trembling on the verge of the Source, his dark eyes so like those of Ngurra, the Yarru elder.

I can only give you the choice, Slayer.

None of them had done such a deed as hers. Because of her, Lord Satoris, Satoris Third-Born, who was once called the Sower, was no more. For that, surely, her death was not undeserved.

“Tanaros!” Ushahin’s voice rose sharply. “ Now.”

He remembered how he had knelt in the Throne Hall, his branded heart spilling over with a fury of devotion, of loyalty, and the words he had spoken. My Lord, I swear, I will never betray you!

Wherein did his duty lie?

Loyal Tanaros. It is to you I entrust my honor.

So his Lordship had said. And Ngurra, old Ngurra … Choose .

Breathing hard, Tanaros lowered his sword. He avoided looking at Cerelinde. He did not want to see her eyes opening, the sweep of her lashes rising as disbelief dawned on her beautiful face.

She whispered his name. “Tanaros!”

“Don’t.” His voice sounded as harsh as a raven’s call. “Lady, if you bear any kindness in your heart, do not thank me for this. Only go, and begone from this place.”

“But will you not—” she began, halting and bewildered.

“No.” Ushahin interrupted. “Ah, no!” He took a step forward, Godslayer still clenched in his fist, pulsing like a maddened heart. “This cannot be, Blacksword. If you will not kill her, I will.”

“No,” Tanaros said gently, raising his sword a fraction. “You will not.”

Ushahin inhaled sharply, his knuckles whitening as his grip tightened. “Will you stand against Godslayer itself?”

“Aye, I will.” Tanaros regarded him. “If you know how to invoke its might.”

For a long moment, neither moved. At last, Ushahin laughed, short and defeated. Lowering the dagger, he took a step backward. “Alas, not yet. But make no mistake, cousin. I know where the knowledge is to be found. And I will use it.”

Tanaros nodded. “As his Lordship intended. But you will not use it today, Dreamspinner.” He turned to Cerelinde. “Take the right-hand door. It leads in a direct path to the quarters of Vorax of Staccia, who died this day, as did so many others. No one will look for you there.” He paused, rubbing at his eyes with the heel of his left hand. “If you are fortunate,” he said roughly, “you may live.”

Her eyes were luminous and grey, glistening with tears. “Will you not come with me, Tanaros?”

“No.” If his heart had not been breaking at his Lordship’s death, at the death of all who had fallen this day, it might have broken at her beauty. “Lady, I cannot.”

“You can ! ” she breathed. “You can still—”

“Cerelinde.” Reaching out with his free hand, Tanaros touched her cheek. Her skin was cool and smooth beneath his fingertips, damp with tears. A Man could spend an eternity loving her, and it would not be long enough. But she had slain his Lordship. Arahila the Fair might forgive her for it, but Tanaros could not. “No.”

Читать дальше