“Can you see anything?” he called up to Lily.

“No, it’s all stupid stained glass. On the other hand, I guess no one will notice if I just break a little bit.”

“Are you sure you should—”

“Cripes, Sacha! Since when did you turn into an old lady? pass me your handkerchief.”

He passed it up to her. A moment later he heard a sharp crack! and the bright tinkle of falling glass.

“Darn!” Lily said. “All I can see is more rooftops. Unless the dybbuk’s chasing pigeons, we’re plumb out of luck.”

“Lily! I think I hear someone coming, Maybe we should go back down.”

“In a minute.” More crackling and tinkling. “I think I might just be able to—”

Before Sacha could protest, Lily had broken several more panes of stained glass and squeezed herself out the window to her waist.

“Wolf told us to stay in the library!”

“I am in the library,” Lily said. “Or at least most of me is.”

Then she gave a sudden gasp of surprise — and her legs and feet vanished as if she’d been pulled out the window by her armpits.

It took less than a second to climb the last few rungs of the ladder, but it felt like the longest second in Sacha’s life.

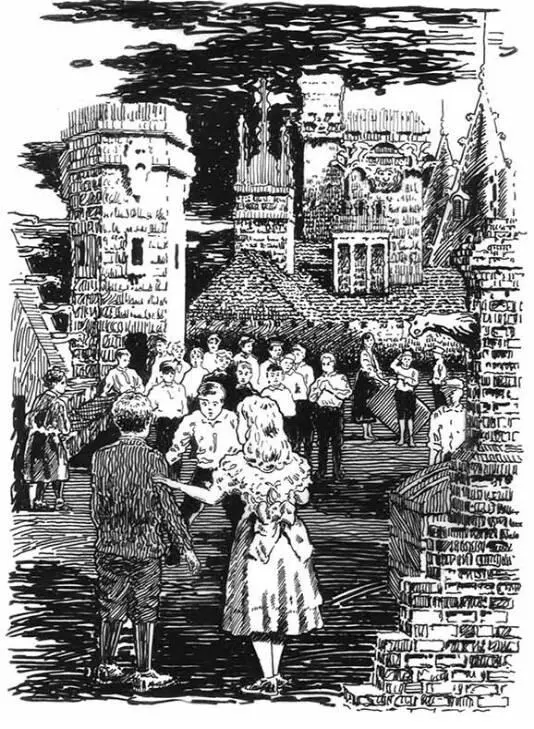

When he looked out, he saw nothing at first but open sky. The library’s soaring vaulted roof stuck out above the rest of Morgaunt’s mansion like the prow of a clipper ship. From up here you saw just how vast the place was. Acres of slate-tiled roof rolled away on all sides, folding into high tors and steep ridgelines. It was like one of those impassable mountain ranges that travelers in old stories were always getting waylaid in. And, like real mountains, the roof’s ridgelines enclosed hidden ravines so narrow that you could walk right past them without ever knowing they existed.

It was one of those ravines that drew Sacha’s attention now. Though he couldn’t see into it, he could hear Lily Astral’s voice coming out of it.

“Do you live up here?” she was asking. “I can’t tell you how jealous I am! I always dreamed of running away from home and joining a Gypsy band that camped out on the rooftops! You must have some ripping good times!”

Sacha squirmed through the broken window and picked his way down the slope of the roof until he caught sight of her. She looked completely in her element. She was balanced on the slope of the roof like a pirate ready to board an enemy ship. She even had a broken-off broomstick clutched in one hand like a sword.

“What’s with the stick?” Sacha asked as he reached her side.

“Oh, when they first pulled me out the window, I thought I might have to thrash ’em. But they’re just kids.” A wistful tone crept into her voice. “And anyway they’re already leaving.”

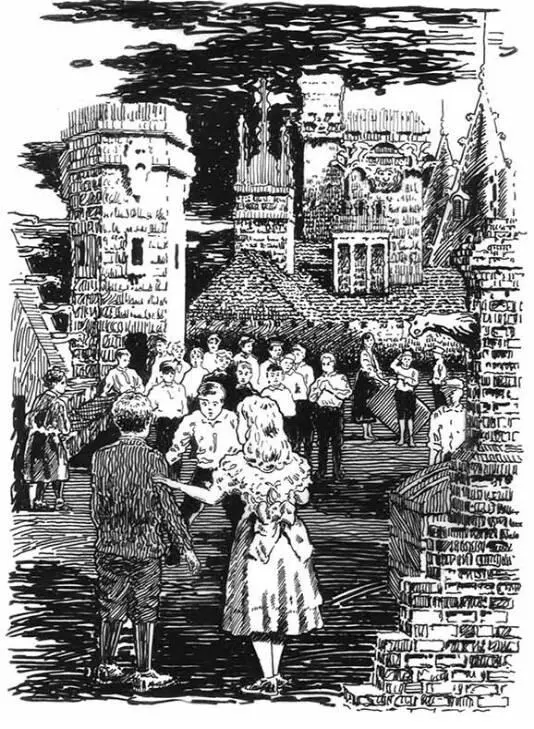

Only then did Sacha notice the little group of children standing at the bottom of the ravine looking up at them.

Lily was right; they were just kids. Most of them were small for their age too, even by Hester Street standards. They were olive-skinned and dark-haired and brown-eyed, and they were dressed like Italians. But not like the prosperous Italians who ran the greengrocers on Prince Street, or even like the poor Italians of Ragpickers’ Row. These children were dressed in brightly embroidered peasant costumes like the newly arrived immigrants Sacha had seen coming off the boats from Ellis Island.

And they were definitely leaving. as Sacha and Lily watched, a harried-looking woman in a flowered head scarf popped around the corner, grabbed two of the kids, and dragged them away, scolding furiously.

“Is that Italian?” Lily asked doubtfully.

“I guess so. But it doesn’t sound like any Italian I ever heard.”

“Come on!” Lily called over her shoulder, already trotting off without waiting to see if Sacha was following. “Let’s see where they’re going!”

The ravine opened onto an undulating valley that stretched for acres in all directions. and Sacha could barely believe what he saw there: an entire shantytown, set up on the roof of Morgaunt’s mansion, where some several dozen women and children seemed to be going about the business of life as naturally and unconcernedly as if they were living at street level instead of hundreds of feet up in the air.

Or rather they had lived there. Now they were leaving — and in a hurry.

“Does anyone here speak English?” Lily called out.

A few of the women stared at them, but the rest just kept packing. Then a sturdy-looking boy a little younger than Sacha came forward. His eyes were red, and his face was streaked with tears. “I speak English,” he said. “What do you want with us?”

“Who are you?” Sacha asked. “What are you doing up here? And why are you leaving?”

“We’re the stonemasons’ families. And we live here. Or we used to. But now we have to leave because my father died, and the police are coming.”

Lily and Sacha stared at the boy, dumbfounded.

“I–I’m sorry,” Sacha said. “Was it the dybbuk?”

The boy shuddered. “If that’s what you call that thing.”

“Did you see it?” Lily asked.

“My mother did. She said it was a shadow in the shape of a person. She said it was made of smoke, and its eyes were blacker than Gesù Bambino .”

“She needs to talk to Inquisitor Wolf right now!”

“What are you, crazy? Why do you think we’re leaving? The last thing we want to do is talk to any cops!”

“But you have to!” Lily pleaded.

It wasn’t going to do any good. Sacha knew that even if Lily didn’t. There was no way these people were ever going to talk to the Inquisitors.

“What’s your name?” Lily demanded.

“Antonio.”

“Antonio what?”

“Why should I tell you? ”

“You can’t just run away!” Lily cried. “The Inquisitors are trying to catch the man who killed your father! Don’t you want him caught? Don’t you want him stopped? ”

“The police don’t care about my father any more than you do,” Antonio scoffed. “And as for stopping his killer, the police don’t need to worry. I’ll take care of that myself.”

Suddenly a woman ran up behind Antonio and began tugging him away from Sacha and Lily. She looked like Antonio, and she would have been very pretty if her hair hadn’t been so disheveled and her eyes so swollen from crying.

As she pulled Antonio away, she was whispering furiously into his ear. Finally he seemed to grasp what she was saying. His dark eyes flashed toward Sacha, and he tried to struggle free. But two more women had come to help his mother, and finally the three of them managed to drag him away.

As Antonio vanished behind a looming Gothic turret, he looked back one more time at Sacha.

In Sacha’s whole life up to that moment, no one had ever looked at him with such naked hatred.

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE. The Lone Gunman

WOLF WAS WAITING for them when they got back to the library, and he was furious.

Not that you could tell that easily. It turned out that Wolf got angry just like Sacha’s father did: no yelling, just a deafening silence that made you feel like getting boxed on the ear would be a welcome relief.

“Go back to the office,” he interrupted when they tried to tell him about Antonio and the stonemasons’ children. “Maybe a day of filing papers for Payton will remind you that this is a real job, not a game.”

Sacha caught the undercurrent of anger in Wolf’s voice immediately and knew they were on seriously thin ice. But Lily just forged right ahead.

Читать дальше