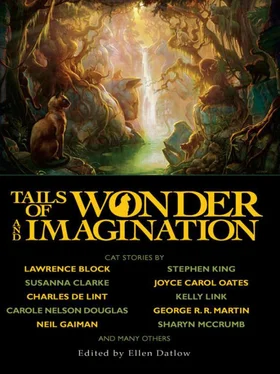

Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, ISBN: 2010, Издательство: Night Shade Books, Жанр: Фэнтези, Фантастика и фэнтези, Ужасы и Мистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Tails of Wonder and Imagination

- Автор:

- Издательство:Night Shade Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:978-1-59780-170-6

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Tails of Wonder and Imagination: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

collects the best of the last thirty years of science fiction and fantasy stories about cats from an all-star list of contributors.

Tails of Wonder and Imagination — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Tails of Wonder and Imagination», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Tuf pressed a series of lights on the console.

A dead thing was lying on a beach, rotting on indigo sands.

It was a still picture, this one, not a tape. Haviland Tuf and Guardian Kefira Qay had a long time to study the dead thing where it sprawled, rich and rotten. Around and about it was a litter of human corpses, lending it scale by their proximity. The dead thing was shaped like an inverted bowl, and it was as big as a house. Its leathery flesh, cracked and oozing pustulence now, was a mottled grey-green. Spread on the sand around it, like spokes from a central wheel, were the thing’s appendages—ten twisted green tentacles, puckered with pinkish-white mouths and, alternately, ten limbs that looked stiff and hard and black, and were obviously jointed.

“Legs,” said Kefira Qay bitterly. “It was a walker, Tuf, before they killed it. We have only found that one specimen, but it was enough. We know why our islands fall silent now. They come from out of the sea, Tuf. Things like that. Larger, smaller, walking on ten legs like spiders and grabbing and eating with the other ten, the tentacles. The carapace is thick and tough. A single explosive shell or laser burst won’t kill one of these the way it would a fire-balloon. So now you understand. First the sea, then the air, and now it has begun on the land as well. The land. They burst from the water in thousands, striding up onto the sand like some terrible tide. Two islands were overrun last week alone. They mean to wipe us from this planet. No doubt a few of us will survive on New Atlantis, in the high inland mountains, but it will be a cruel life and a short one. Until Namor throws something new at us, some new thing out of nightmare.” Her voice had a wild edge of hysteria.

Haviland Tuf turned off his console, and the telescreens all went black. “Calm yourself, Guardian,” he said, turning to face her. “Your fears are understandable but unnecessary. I appreciate your plight more fully now. A tragic one indeed, yet not hopeless.”

“You still think you can help?” she said. “Alone? You and this ship? Oh, I’m not discouraging you, by any means. We’ll grasp at any straw. But…”

“But you do not believe,” Tuf said. A small sigh escaped his lips. “Doubt,” he said to the grey kitten, hoisting him up in a huge white hand, “you are indeed well named.” He shifted his gaze back to Kefira Qay. “I am a forgiving man, and you have been through many cruel hardships, so I shall take no notice of the casual way you belittle me and my abilities. Now, if you might excuse me, I have work to do. Your people have sent up a great many more detailed reports on these creatures, and on Namorian ecology in general. It is vital that I peruse these, in order to understand and analyze the situation. Thank you for your briefing.”

Kefira Qay frowned, lifted Foolishness from her knee and set him on the ground, and stood up. “Very well,” she said. “How soon will you be ready?”

“I cannot ascertain that with any degree of accuracy,” Tuf replied, “until I have had a chance to run some simulations. Perhaps a day and we shall begin. Perhaps a month. Perhaps longer.”

“If you take too long, you’ll find it difficult to collect your two million,” she snapped. “We’ll all be dead.”

“Indeed,” said Tuf. “I shall strive to avoid that scenario. Now, if you would let me work. We shall converse again at dinner. I shall serve vegetable stew in the fashion of Anon, with plates of Thorite fire mushrooms to whet our appetites.”

Qay sighed loudly. “Mushrooms again?” she complained. “We had stir-fried mushrooms and peppers for lunch, and crisped mushrooms in bitter cream for breakfast.”

“I am fond of mushrooms,” said Haviland Tuf.

“I am weary of mushrooms,” said Kefira Qay. Foolishness rubbed up against her leg, and she frowned down at him. “Might I suggest some meat? Or seafood?” She looked wistful. “It has been years since I’ve had a mud-pot. I dream of it sometimes. Crack it open and pour butter inside, and spoon out the soft meat, you can’t imagine how fine it was. Or sabrefin. Ah, I’d kill for a sabrefin on a bed of seagrass!”

Haviland Tuf looked stern. “We do not eat animals here,” he said. He set to work, ignoring her, and Kefira Qay took her leave. Foolishness went bounding after her. “Appropriate,” muttered Tuf, “indeed.”

Four days and many mushrooms later, Kefira Qay began to pressure Haviland Tuf for results. “What are you doing?” she demanded over dinner. “When are you going to act? Every day you seclude yourself and every day conditions on Namor worsen. I spoke to Lord Guardian Harvan an hour ago, while you were off with your computers. Little Aquarius and the Dancing Sisters have been lost while you and I are up here dithering, Tuf.”

“Dithering?” said Haviland Tuf. “Guardian, I do not dither. I have never dithered, nor do I intend to begin dithering now. I work. There is a great mass of information to digest.”

Kara Qay snorted. “A great mass of mushrooms to digest, you mean,” she said. She stood up, tipping Foolishness from her lap. The kitten and she had become boon companions of late. “Twelve thousand people lived on little Aquarius,” she said, “and almost as many on the Dancing Sisters. Think of that while you’re digesting, Tuf.” She spun and stalked out of the room.

“Indeed,” said Haviland Tuf. He returned his attention to his sweet-flower pie.

A week passed before they clashed again. “Well?” the Guardian demanded one day in the corridor, stepping in front of Tuf as he lumbered with great dignity down to his work room.

“Well,” he repeated. “Good day, Guardian Qay.”

“It is not a good day,” she said querulously. “Namor Control tells me the Sunrise Islands are gone. Overrun. And a dozen skimmers lost defending them, along with all the ships drawn up in those harbors. What do you say to that?”

“Most tragic,” replied Tuf. “Regrettable.”

“When are you going to be ready?”

He gave a great shrug. “I cannot say. This is no simple task you have set me. A most complex problem. Complex. Yes, indeed, that is the very word. Perhaps I might even say mystifying. I assure you that Namor’s sad plight has fully engaged my sympathies, however, and this problem has similarly engaged my intellect.”

“That’s all it is to you, Tuf, isn’t it? A problem?”

Haviland Tuf frowned slightly, and folded his hands before him, resting them atop his bulging stomach. “A problem indeed,” he said.

“No. It is not just a problem. This is no game we are playing. Real people are dying down there. Dying because the Guardians are not equal to their trust, and because you do nothing. Nothing.”

“Calm yourself. You have my assurance that I am laboring ceaselessly on your behalf. You must consider that my task is not so simple as yours. It is all very well and good to drop bombs on a dreadnaught, or fire shells into a fire-balloon and watch it burn. Yet these simple, quaint methods have availed you little, Guardian. Ecological engineering is a far more demanding business. I study the reports of your leaders, your marine biologists, your historians. I reflect and analyze. I devise various approaches, and run simulations on the Ark ’s great computers. Sooner or later I shall find your answer.”

“Sooner,” said Kefira Qay, in a hard voice. “Namor wants results, and I agree. The Council of Guardians is impatient. Sooner, Tuf. Not later. I warn you.” She stepped aside, and let him pass.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

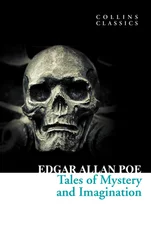

Похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.