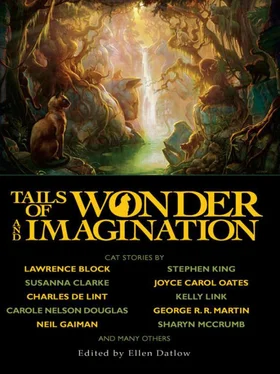

Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, ISBN: 2010, Издательство: Night Shade Books, Жанр: Фэнтези, Фантастика и фэнтези, Ужасы и Мистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Tails of Wonder and Imagination

- Автор:

- Издательство:Night Shade Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:978-1-59780-170-6

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Tails of Wonder and Imagination: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

collects the best of the last thirty years of science fiction and fantasy stories about cats from an all-star list of contributors.

Tails of Wonder and Imagination — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Tails of Wonder and Imagination», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Then he saw the Old Man curled into a ball on the hill, halfway down to the beach, a white blur among the grey of water falling; Old Foss ran to him.

Old Foss whispered in his ear, “Come, Old Man. Time to come in, the water is falling fast and your nightshirt is thin.”

“She came to me in my dreams,” the Old Man shouted suddenly, his eyes opening wide and wild, “she came to me in my dreams. They’ve come again in the sieve to take me to sea.”

“This would be the last time,” Old Foss said. “Wait a little while longer and we will find ways to pass the time—painting unfinished pictures by the shore, or you can pet me by the fire when it rains, or….”

He didn’t know what to say. Could he do this to the Old Man again, take him from his Jumbly Girl?

For the Jumblies were by the shore, and the Jumbly Girl was with them. As the rain lessened they came into sight. She was leaving them and wandering up the hill, a ghost in green, her voice on the wind:

“Come with us, come to stay, and we will sail under the sea, and we will never leave but we will never want to….”

Old Foss turned away from looking at her.

I suppose you should go, Old Foss thought, I suppose you could go and I should stay for I only wanted you for myself, an old debt I will never be able to repay. He didn’t say it because it hurt too much to say it.

But the Old Man did not turn his head to look at his Jumbly Girl.

She came closer, calling again, “Come, come, come to sea, to the sieve that sinks below the waves until we drown, to the lost worlds below the sun.”

But the Old Man did not turn his head.

The Jumbly Girl stopped. “Can’t you hear me, love?”

Old Foss dared not turn to look at her again. The Old Man did not hear. He could not see. Old Foss would not give away her presence.

The Jumbly Girl stood, her body heaving, crying Old Foss supposed, but the rain made that indeterminate. That at least was what he tried to tell himself.

The Old Man cried, too, and that he could see despite the rain, for the Old Man beat his breast and tore at his thinning hair, and pulled hard on his frumpy old beard until he pulled the hair out in uneven patches.

“I want to die,” the Old Man said, as the Jumbly Girl reached out for him with arms of green embrace, with love forever and ever for him, to death, yes certainly to death but perhaps beyond as well.

“I’m sorry I made a mistake, so long ago,” Old Foss said, “that time by the river of night, I should have let you drown. Or maybe you have with me.”

But the Old Man didn’t hear, or couldn’t listen.

Old Foss mewed piteously, wet through.

“Oh, Old Foss,” the Old Man said, “look at you, oh, you’re wet through.”

Old Foss shivered and looked to him like he had looked to him once long ago as a kitten lost in the rain.

“Come on, Old Foss, let’s go home,” the Old Man said, rising, pulling Old Foss against him, heading back up the hill. “They’re not coming after all.” He choked on the words. “They’re not here.”

The Old Man leaned over Old Foss, and Old Foss peered over the Old Man’s shoulder to see the Jumblies come in a heap to the Jumbly Girl crying on the hill. They covered her in their love, with their arms at all angles and their boots kicking out, and their eyes green compassion. They smiled a blue benediction.

“I’m sorry,” they said to the Jumbly Girl, and turning they all walked, or rolled, or shambled downhill. “I’m sorry,” they said together and held her in their arms until they vanished in rain.

“Home again soon,” the Old Man said, soothing, but tired like a drunk man sobered by sorrow on his way home again from a lost night on the town, or like a storm-tossed sailor thrown on the shore, wobbling inland to safety.

“It’s all right, it’s all right, it’s all right, Old Foss.”

“I’m sorry,” Old Foss said.

“There, there,” the Old Man said, though he couldn’t hear. “It’s all right. It’s all right.”

But it wasn’t.

A SAFE PLACE TO BE

Carol Emshwiller

Carol Emshwiller grew up in both Michigan and France and currently divides her time between New York and California. She is the winner of two Nebula Awards for her stories “Creature” and “I Live With You.” She has also won the World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement. She’s been the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts grant and two New York State grants. Her short fiction has been published in many literary and science fiction magazines and her most recent books are the novels Mister Boots and The Secret City , and the collection I Live With You and You Don’t Know It . A new collection is forthcoming from P.S. Publishing.

Emshwiller says: “I had no special cat in mind. I haven’t had a cat for a long time but I like to use animals in my stories in all sorts of ways. We used to have a marmalade cat like this one. Before he was altered, he used to get in a fight every night—came back with torn ears all the time. He went off to college with my daughter where he lived with a batch of students who had a pet rabbit. Then he came back, got fat, and lived a long, lazy life.”

It started with a funny feeling in the bottoms of my feet. Something is going to happen. Perhaps an earthquake. That’s what it feels like. But perhaps terrorists on the way. Whatever it is, something’s coming.

Why did I (of all people), an old lady, get this warning while everybody else is going on as usual? Have I a special talent nobody else has?

But the cat feels it, too. He’s been shaking his paws as if they feel exactly like my feet do. He looks at me as if to say: Why don’t you do something? I tell him, “I will.”

It’s coming closer. I’m getting out of here before everybody tries to leave at the same time.

Though could it be that I’m just feeling the future in general. Disaster will come to all of us and at my age it can’t be that far away. I’ll be as dead as most all of humanity already is. Mother… Dad… Dostoyevsky.

But can I take a chance that this tingly feeling is just because of the normal run of things?

If only I knew when. And also who to tell? I’d like company through all this. Not that a good cat isn’t company enough and I do talk things over with him, but a person would be nice, too. I can’t think of anybody to tell who would believe me or wouldn’t just get in my way as I try to leave in search of safety.

That tingly, rattley vibration is getting worse, rising from the ground, up through my feet and rattling my spine. This morning I could even feel it from my fifth floor apartment. I ran for the central hallway. I stood there for twenty minutes. Then I grabbed Natty, put his harness and leash on him, and ran outside and down the block and huddled under a tree. Again I waited. The cat was shaking as much as I was. A sure sign that I’m right. I ran farther but had to stop to catch my breath in a doorway near the park.

Here, in a place where pigeons are always wobbling along, there wasn’t a single one. Not one! That scared both of us even more.

I must have looked just how I felt because somebody asked me what was wrong. I said, “Just a dizzy spell is all.” I didn’t want anybody else to know. I wanted to get out and safely away before any of the others found out something was going to happen.

I check the feelings in my feet again. I feel a rumbling for sure, by now so strong I wonder why everybody doesn’t feel it. Well, all the better then, it gives me plenty of time to escape.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

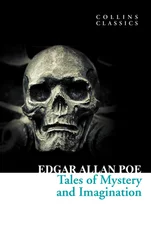

Похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.