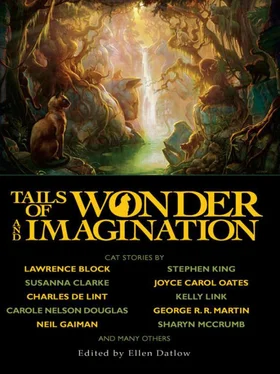

Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ellen Datlow - Tails of Wonder and Imagination» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2010, ISBN: 2010, Издательство: Night Shade Books, Жанр: Фэнтези, Фантастика и фэнтези, Ужасы и Мистика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Tails of Wonder and Imagination

- Автор:

- Издательство:Night Shade Books

- Жанр:

- Год:2010

- ISBN:978-1-59780-170-6

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Tails of Wonder and Imagination: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

collects the best of the last thirty years of science fiction and fantasy stories about cats from an all-star list of contributors.

Tails of Wonder and Imagination — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Tails of Wonder and Imagination», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Joyce says: “While I was still trying to get published as a writer I lived on the Greek islands for a while, and I spent six months in Chania on the west of Crete. It had been under Ottoman rule for some centuries, when the name of the town was Candia. While I was there someone led me to a strange nightclub behind the old spice warehouses on the seafront. The person who took me there left the island suddenly and I was never able to find the place again. At the place where I thought it should be an empty building was home to a number of feral cats, and that last detail was what triggered the story.”

Candia. It was surely in Candia, with its crumbling Venetian waterfront and its abandoned minarets, and its harbor sliding into the rose-coloured sea further by an inch every day. Just like Ben Wheeler when I first spotted him, with his bottle of raki at his permanent station outside the Black Orchid Café, a misted tumbler forever fixed at some point on the arc between tabletop and bottom lip.

I had just climbed down from the rusting, antiquated bus, the sole passenger to disembark in that dusty square, when I saw him, at a time when I never expected to see again anyone I’d ever known.

His glass of raki arrested itself on its mechanical ascent, and he peered across the rim of his tumbler directly into my eyes. He was sitting at a table on the concrete edge of the neglected wharf. Over his shoulder the sun was punctured on a derelict minaret, spilling lavender and molten gold across the motionless waters of the harbor. He took a sip from his glass, and turned away.

“Wheeler,” I called. “Hey, Wheeler!”

On hearing his name he spun round and looked at me again, this time with an expression of incredulity and horror. Then he looked around wildly, as if for egress. For a moment I thought he was actually going to make a break for it and run away from me. I crossed the square to the café and dragged a seat from under the table; but as he showed no sign that he would allow me to join him, I was made to hover.

“Don’t you remember me?” I asked.

Before I got an answer a singer struck up in the square. He had a cardboard shoe-box for donations and was singing in that curious, deep-throated and unaccompanied resitica of the dispossessed people from the mountains. The sound was of almost unendurable melancholy and sweetness, and the guttural voice resonated along the baked brickwork.

Wheeler put down his glass and hooked his thumbs in his waistband, regarding me with an unblinking gaze. I wasn’t fooled. He was clearly nervous. It was as if he had somewhere important to go, but in his astonishment at seeing me there, he couldn’t tear himself away.

“So what are you doing here?” I asked.

He eyed me steadily. “I might ask you the same question.”

He looked back at the square and stroked the white stubble of his beard. Again I got the impression I was detaining him from something important.

“I’ve come here to drink myself to death,” I joked. At least, it was a truth hidden inside a joke, but he nodded seriously, as if this was perfectly reasonable.

The arrival of a waiter brought a moment’s relief. Slow to spot him, Wheeler turned suddenly and fixed the waiter with his extraordinary gaze. The boy shuffled uncomfortably, tapping the steel disc of his tray against his thigh.

“Let me stand you a drink,” I suggested.

Wheeler put his hand to his mouth, removing something very small from the tip of his tongue. “Sure.” He let his eyes drop. “Sit down. I’ll have a beer. Yes, I’ll have a beer.”

I sat, but I was already beginning to regret this. Ben Wheeler looked terrible. I could see a ring of filth on the collar of his short-sleeved shirt. The hems of his oil-spotted chinos were rolled and his bare feet were thrust inside a pair of rotting, rope-soled espadrilles. When the beer arrived, he slurped it greedily. We sat in a stiff silence for a while, the swelling vocalizations of the resitica man the only other sound in the square in the parched heat of the afternoon.

Our paths had crossed briefly in the eighties, when we were both working for Aid-Direct, the notorious London-based charity, three or four years before public scandal closed the outfit down. Wheeler, Director of Fundraising at the time, was a flamboyant character in a double-breasted suit and sixties haircut that looked like it was woven out of brown twill. For some of the serious-minded charity workers he was too fond of champagne, parties and pretty girls, but he could bring in money the way a poacher can tickle trout from a stream. The eighties. New money wanted to log onto charitable causes, not out of any sense of philanthropy, but to clamber aboard the Queen’s Honours List. Wheeler obliged by organizing fatcat charity parties, in which city stockbrokers and dealers would be photographed sipping champers from a Page Three girl’s shoe, all before writing a cheque.

After one of these all-night jamborees at the Savoy or the Dorchester, a sack of rice or two would end up on a truck bound for Ethiopia or Somalia. At the time I didn’t care where the money came from, or how little of it found a way through so long as it assisted me in my plans to change the world. Or rather, I wasn’t so naïve as to believe one could change the world, but I did believe it was possible to change one person’s world, and that was good enough for me.

I’d only been working for Aid-Direct about six months before accountants were called in. No one was ever told why, but Wheeler was suddenly given an impressive golden handshake. After the farewell party, I got caught in the lift with him. He was smashed.

“Hey,” he said that day, “Something I wanna do, ’fore I leave here.”

“What,” I said, my finger hovering over the lift button.

He swayed dangerously. “Young tart who works in your office. Wassname. Cat-like. Yum yum. Feline.” I offered no help, and he supplied the name himself “Sarah.”

“What about her?” The lift started its descent.

“Afore I go. Ten minutes wiv Sarah the feline. In the store cupboard. Hey. Ten minutes.”

“Good luck.”

“No no,” he said, brushing imaginary lint from the front of my jacket. “I want you to ask her for me.”

“Get out of here!” The lift door opened.

His huge, manicured hand restrained me as I made to step out of the lift. Fumbling in his pocket, he produced a couple of banknotes and stuffed them in my breast pocket. “Ask her.”

“Piss off.”

More banknotes, stuffed in with the others. “Ask her for me.”

Still more. Big denomination. “Just ask her for me.” He patted my cheek with his be-ringed paw.

We got out of the lift and I went back to my office, where Sarah was audio-typing. With her lithe figure and her long, raven hair scraped back from her face and tied at the back, Sarah cut a figure like a ballerina. Who wouldn’t want ten minutes with Sarah? I did. I’d taken her out a few times. Despite some lavish wining and dining, she’d resisted all my best efforts. Any man who has tried and failed to seduce a particular woman nurses a tiny malice, and I confess to giving way to a disgraceful and sadistic instinct to collude with Wheeler’s drunken lust.

I gently lifted one of her earphones. “We need some more envelopes. Can you go get ’em?”

“Now?”

“Please.”

“What’s the rush?”

She looked at me quizzically as I turned my back. I heard her replacing her headset on the table. The door closed as she went out. Half an hour later she was back, flushed and looking like she’d learned some new wrestling holds.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

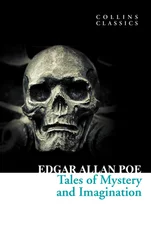

Похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Tails of Wonder and Imagination» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.