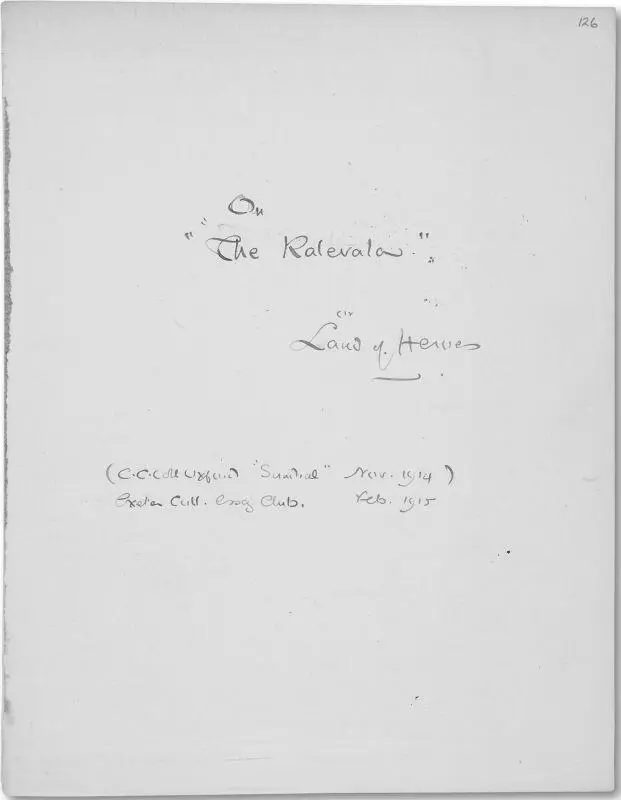

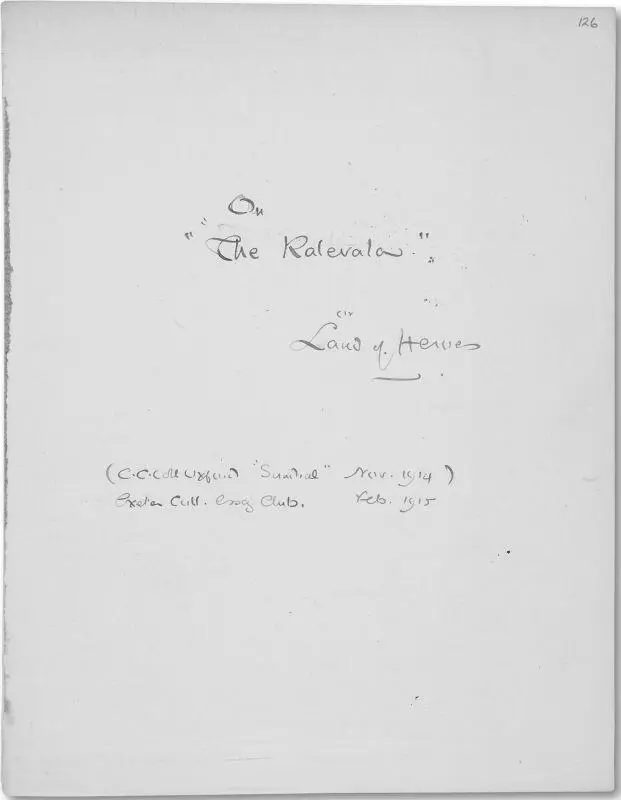

The hand-written title page to the manuscript (Plate 6) reads ‘On “The Kalevala” or Land of Heroes’, and also bears the notations ‘(C.C. Coll. [Corpus Christi College] Oxford ‘Sundial’ Nov. 1914)’ and ‘Exeter Coll. Essay Club. Feb. 1915’, the two dates on which Tolkien is known to have delivered the talk. The November 1914 presentation, given a bare month after his October letter to Edith, and the February one given a scant three months later, clearly belong to the same period as the story.

No firm date can be assigned for the somewhat revised typescript draft, which has no separate title page, but only the heading ‘The Kalevala’. A reference in the text to the ‘late war’ would place it after the World War I Armistice of 11 November 1918, and an allusion to the ‘League’ (presumably the League of Nations formed in 1919–20) would suggest 1919 as a terminus a quo . On the basis of comparison with material in Tolkien’s early poetry manuscripts and typescripts Douglas A. Anderson suggests 1919–21 (personal communication), while Christina Scull and Wayne Hammond propose a somewhat later, admittedly conjectural dating of ‘?1921–?1924’ ( Chronology , p. 115). Anderson’s date would place the revision at a time when Tolkien was still living in Oxford (he was on the staff of the New English Dictionary from November 1918 to the spring of 1920), while the Scull-Hammond three-year time frame would push it to the period when Tolkien was Reader in English Language at Leeds University. In either case, there is no available evidence that this revised version of the talk was ever given.

As with The Story of Kullervo , I have edited both essays’ transcriptions for smooth reading. Square brackets enclose words or parts of words missing from the text but supplied where necessary for clarity. False starts, cancelled words and lines have been omitted. Also as with the story, I have chosen not to interrupt the texts (and distract the reader) with note numbers, but a Notes and Commentary section follows each essay proper, explaining terms and usages, and citing references.

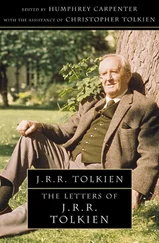

6. Manuscript title page of the essay, ‘On “The Kalevala”’, written in J.R.R. Tolkien’s hand [MS Tolkien B 61 folio 126 recto].

On ‘The Kalevala’

or

Land of Heroes

[Manuscript draft]

I am afraid this paper was not originally written for this society, which I hope it will pardon since I produce it mainly to form a stop-gap tonight, to entertain you as far as possible in spite of the sudden collapse of the intended reader.

I hope the society will also forgive besides its second-hand character its quality: which is hardly that of a paper — rather a disconnected soliloquy accompanied by a leisurely patting on the back of a pet volume. If I continually drop into talking as if no one in the room had read these poems before, it is because no one had, when I first read it; and you must also attribute it to the pet attitude. I am very fond of these poems: they are litterature[ sic ] so very unlike any of the things that are familiar to general readers, or even to those versed in the more curious by paths: they are so un-European and yet could only come from Europe.

Any one who has read this collection of ballads (more especially in the original which is vastly different to any translation) will I think agree to that. Most people are familiar from the age of their earliest books onward with the general mould and type of mythological stories, legends, Romances that come to us from many sources: from Hellas by many channels, from the Celtic peoples Irish and British, and from the Teutonic (I put these in order of increasing appeal to myself); and which achieve forums, with their crowning glory in Stead’s Books for the Bairns : that mine of ancient lore. They have a certain style or savour; a something akin to one another in spite of their vast cleavages that make you feel that whatever the difference of ultimate race of those speakers there is something kindred in the imagination of the speakers of Indo-European languages.

Trickles come in from a vague and alien East of course (it is even reflected in the above beloved pink covers) but alien influence, if felt, is more on the final litterary shapes than on the fundamental stories. Then perhaps you discover the Kalevala, (or to translate it roughly: it is so much easier to say) the Land of Heroes; and you are at once in a new world; and can revel in an amazing new excitement. You feel like Columbus on a new Continent or Thorfinn in Vinland the good. When you first step onto the new land you can if you like immediately begin comparing it with the one you have come from. Mountains, rivers, grass, and so on are probably common features to both. Some plants and animals may seem familiar especially the wild and ferocious human species; but it is more likely to be the often almost indefinable sense of newness and strangeness that will either perturb you or delight you. Trees will group differently on the horizon, the birds will make unfamiliar music; the inhabitants will talk a wild and at first unintelligible lingo. At the worst I hope, however, that after this the country and its manners have become more familiar, and you have got on speaking terms with the natives, you will find it rather jolly to live with this strange people and these new gods awhile, with this race of unhypocritical scandalous heroes and sadly unsentimental lovers: and at the last you may feel you do not want to go back home for a long while if at all.

This is how it was for me when I first read the Kalevala— that is, crossed the gulf between the Indo-European-speaking peoples of Europe into this smaller realm of those who cling in queer corners to the forgotten tongues and memories of an elder day. The newness worried me, sticking in awkward lumps through the clumsiness of a translationwhich had not at all overcome its peculiar difficulties; it irritated and yet attracted: and each time you read it the more you felt at home and enjoyed yourself. When H. Modsshould have been occupying all my forces I once made a wild assault on the stronghold of the original language and was repulsed at first with heavy losses: but it is easy almost to see the reason why the translations are not at all good; it is that we are dealing with a language separated by a quite immeasurable gulf in method and expression from English.

There is however a possible third case which I have not considered: you may be merely antagonistic and desire to catch the next boat back to your familiar country. In that case before you go, which had best be soon, I think it only fair to say that if you feel that heroes of the Kalevala do behave with a singular lack of conventional dignity and with a readiness for tears and dirty dealing, they are no more undignified and not nearly so difficult to get on with as a medieval lover who takes to his bed to weep for the cruelty of his lady, in that she will not have pity on him and condemns him to a melting death; but who is struck with the novelty of the idea when his kindly adviser points out that the poor lady is as yet uninformed in any way of his attachment. The lovers of the Kalevala are forward and take a deal of rebuffing. There is no Troilus to need a Pandarusto do his shy wooing for him: rather here it is the mothers-in-law who do some sound bargaining behind the scenes and give cynical advice to their daughters calculated to shatter the most stout illusions.

One repeatedly hears the ‘Land of Heroes’ described as the ‘national Finnish Epic’: as if a nation, besides if possible a national bank theatre and government, ought also automatically to possess a national epic. Finland does not. The K[alevala] is certainly not one. It is a mass of conceivably epic material: but, and I think this is the main point, it would lose nearly all that which is its greatest delight if it were ever to be epically handled. The main stories, the bare events, alone could remain; all that underworld, all that rich profusion and luxuriance which clothe them would be stripped away. The ‘L[and] of H[eroes]’ is in fact a collection of that delightful absorbing material which, on the appearance of an epic artist, because of its comparative lowness of emotional pitch, has elsewhere inevitably been cast aside and afterwards overshadowed (far too often) has vanished into disuse and utter oblivion.

Читать дальше