The Story of Kullervo

by

J.R.R. Tolkien

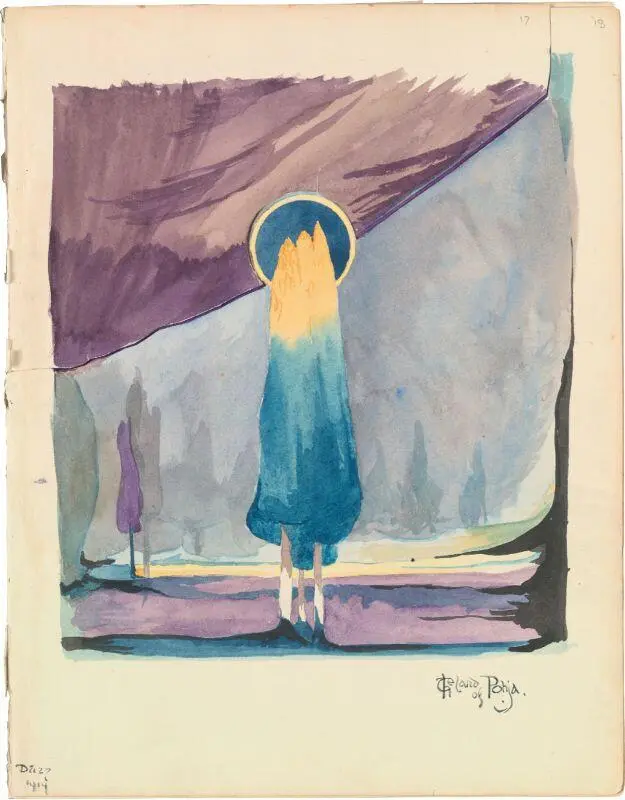

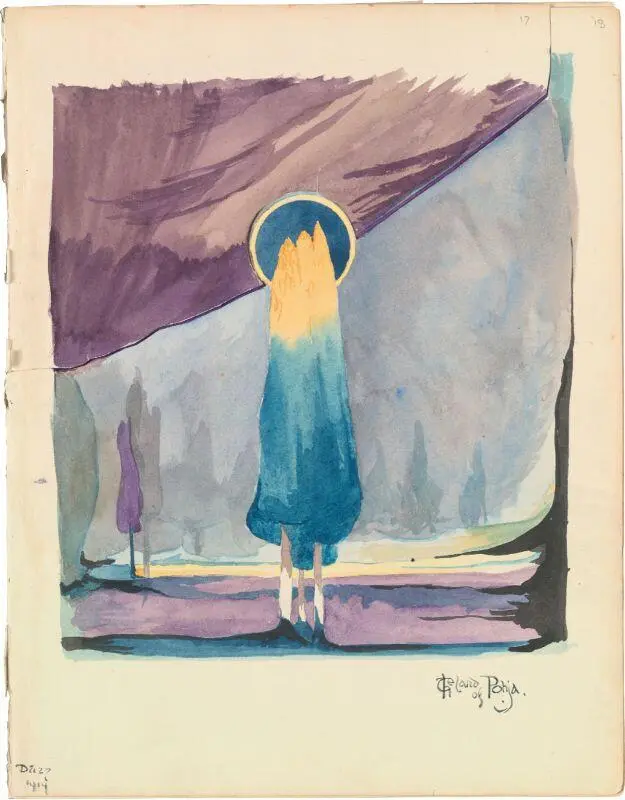

The Land of Pohja by J.R.R. Tolkien

1. Manuscript title page written in Christopher Tolkien’s hand.

2. First folio of the manuscript.

3. Draft list of character names.

4. Discontinuous notes and rough plot synopsis.

5. Further rough plot synopses.

6. Manuscript title page of the essay, ‘On “The Kalevala”’, written in J.R.R. Tolkien’s hand.

The Land of Pohja by J.R.R. Tolkien

Kullervo son of Kalervo is, perhaps, the least ingratiating of Tolkien’s heroes: uncouth, moody, bad-tempered and vengeful, as well as physically unattractive. Yet those traits add realism to his character, making him perversely appealing in spite of, or perhaps because of, them. I welcome the chance to introduce this complex character to a wider readership than heretofore. I am also grateful for the opportunity to refine my first transcription of the manuscript, restore inadvertent omissions, emend conjectural readings, and correct typos that found their way into print. The present text is, I hope, an improved representation of what Tolkien intended.

Since the story’s initial appearance, further work has been done on its role in the development of Tolkien’s early proto-language, Qenya. John Garth and Andrew Higgins have explored the names of both people and places in the surviving drafts and related them to his language invention, John in his article ‘The road from adaptation to invention’ ( Tolkien Studies Vol. XI, pp. 1–44), and Andrew in Chapter Two of his ground-breaking PhD dissertation on Tolkien’s early languages, ‘The Genesis of J.R.R. Tolkien’s Mythology’ (Cardiff Metropolitan University, 2015). Their work adds to our knowledge of Tolkien’s early efforts, and enriches our understanding of his legendarium as a whole.

The materials here published, J.R.R. Tolkien’s unfinished early work The Story of Kullervo and the two drafts of his Oxford University talk on its source ‘On “The Kalevala”’, first appeared in Tolkien Studies Volume VII in 2010, and I am grateful for the permission of the Tolkien Estate to reprint them here. My Notes and Comments are reprinted with the permission of West Virginia University Press. My essay, ‘Tolkien, Kalevala , and “The Story of Kullervo”’, is reprinted with the permission of Kent State University Press.

Thanks for the present volume go to several people, without whom it would never have come to be. First of all to Cathleen Blackburn, to whom I first proposed that The Story of Kullervo needed to reach a larger audience than that of a scholarly journal. I am grateful to Cathleen for ushering the project through the permissions process of the Tolkien Estate and its publisher, HarperCollins. I am grateful to both the Estate and HarperCollins for agreeing with me that re-publication as a stand-alone was what Tolkien’s Kullervo merited. Thanks also to Chris Smith, Editorial Director at HarperCollins in charge of matters Tolkienian, for his help, advice, and encouragement in bringing Tolkien’s The Story of Kullervo to the wider audience it deserves.

The Story of Kullervo needs to be looked at from several angles if we are to appreciate fully its place in J.R.R. Tolkien’s body of work. It is not only Tolkien’s earliest short story, but also his earliest attempt to write tragedy, as well as his earliest prose venture into myth-making, and is thus a general precursor to his entire fictional canon. In a narrower focus it is a seminal source for what has come to be called his ‘mythology for England’, the ‘Silmarillion’. His retelling of the saga of hapless Kullervo is the raw material from which he developed one of his most powerful stories, that of the Children of Húrin. More specifically still, the character of Kullervo was the germ of Tolkien’s mythology’s most — some would say its only — tragic hero, Túrin Turambar.

It has long been known from Tolkien’s letters that his discovery as a schoolboy of Kalevala or ‘Land of Heroes’, a then recently-published collection of the songs or runos of unlettered peasants in Finland’s rural countryside, had a powerful impact on his imagination and was one of the earliest influences on his invented legendarium. In his 1951 letter describing his mythology to the publisher Milton Waldman Tolkien voiced the concern he had always had for the mythological ‘poverty’ of his own country. It was lacking in his eyes, ‘stories of its own’ comparable to the myths of other countries. There was, he wrote, ‘Greek, and Celtic, and Romance, Germanic, Scandinavian’, and (singled out for special mention) ‘Finnish,’ which he said, ‘greatly affected’ him ( The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien , p. 144, hereafter Letters ). Affect him it most certainly did, his engagement with it nearly ruining his Honour Moderations examinations of 1913, as he confessed to his son Christopher in 1944 ( Letters ,p. 87), and ‘set[ting] the rocket off in story’, as he wrote to W.H. Auden in 1955 ( Letters , pp. 214–15).

At the time Tolkien was working on his story its source, the Finnish Kalevala , was a latecomer to the existing corpus of world mythologies. Unlike the myths of longer literary provenance such as the Greek and Roman, or the Celtic or Germanic, the songs of Kalevala were gathered and published only in the mid-19th century by a professional physician and amateur folklorist, Elias Lönnrot. So different in tone were these songs from the rest of the European myth corpus that they brought about a re-evaluation of the meaning of such terms as epic and myth . {1} 1 They also raised questions about the role of the collector in selecting, editing, and presenting what is collected, leading to the accusation, specific to Kalevala , of ‘folklore or fakelore’; but that is a subject for a different discussion. When Tolkien was first reading Kalevala he and others took it at face value.

Difference and re-evaluation notwithstanding, the publication of Kalevala had a profound effect on the Finns, who had lived under foreign rule for centuries — as part of Sweden from the 13th century to 1809, and from then to 1917 as a sub-set of Russia to which large parts of Finnish territory were ceded by Sweden. The discovery of an indigenous Finnish mythology, coming as it did at a time when myth was becoming associated with nationalism, gave the Finns a sense of cultural independence and a national identity, and made Lönnrot a national hero. Kalevala energized a burgeoning Finnish nationalism and was influential in Finland’s declaration of independence from Russia in 1917. It seems more than possible that Kalevala ’s impact on the Finns as ‘a mythology for Finland’ might have made as deep an impression on Tolkien as the songs themselves, and played a major part in his expressed desire to create his so-called ‘mythology for England’, though what he actually described was a mythology that he could ‘dedicate’ to England ( Letters, p. 144). The fact that he would go on to absorb his Kullervo into the character of his own mythology’s Túrin Turambar is evidence of Kalevala ’s continuing influence on his creativity.

Читать дальше