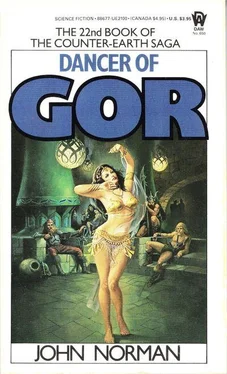

DANCER OF GOR

(Volume twenty-two in the Chronicles of Counter-Earth)

by John Norman

I knew that I did not conform to the cultural stereotypes prescribed to me. I had known this for a long time. The dark secrets which lay hidden within me. I had been forced to conceal for several years. I do not know from whence the secrets arose. They were directly contrary to everything that had been taught to me. Their origins, it seemed, were deep within me, and, I feared, as I lay awake at night afraid, sweating and distraught, native to my very nature. But such a nature, I wept, could not be, and if it were, so subtle, so insistent, so persistent, so unrelenting, so tenacious, it must never be admitted, never, never! Yes, I fought them, these secrets, these covert knowledges, these anticipations, these dreams. Yes, I struggled, in accord with the demands of my culture, my training and education, these things telling me how I must be, how I must be as I was told to be, to drive them from me. I repudiated them, again and again, but to no avail. They returned, ever again, mercilessly, horrifying me, taunting and mocking me, stripping me in the darkness of my bed of my pretenses and lies. I squirmed and thrashed in my bed, twisting and weeping, pounding it with my fists, crying out, "No! No!". Then I would put my head fearfully on my pillow, dampened with meaningless, rebellious tears. Could I be so weak and terrible? Could I be truly so different from others? Surely there could be no one in the world so degraded, so shameful and terrible as myself. Then one night I rose from bed and went to the vanity and lit the small candle there. I had bought this candle weeks before, probably because deep within me, within my deepest self, in my anguished mind, in my tortured breast and heart, I knew this night would come. I lit the small candle. I stood there in the flickering light, for some minutes, looking at myself. I wore a white nightgown, ankle length. I had dark hair and eyes. At that time my hair was cut at shoulder length. Then, not looking back to the mirror, I crept in the candlelight and shadows to the dresser and there, from beneath several layers of garments, where I had concealed it, I drew forth a small bit of scarlet cloth, tiny and silken, with shoulder straps, a garment I had myself sewn weeks ago, one in which, save for fittings, often done by feel, with my eyes closed, I never even dared to look upon myself. This, in a sense, was the third such garment I had attempted. The material for the first, not yet even touched by need and thread, or scissors, I had suddenly discarded in terror, months ago. I had actually begun work on the second garment, some two months ago, but, in touching it to my body, for it was the sort of garment which touches the body directly, with no intervening investiture, I had suddenly, comprehending its meaning and nature, begun to shake with terror and, scarcely knowing what I was doing, I feverishly cut and tore it to pieces, and threw it away! But even as I had destroyed it I knew, weeping and distraught, terrified, I would make another. I took the third garment from the drawer. Suddenly I thrust it back in the drawer, again under the other garments, thrusting shut the drawer. Then, after a moment, breathing heavily, trembling, I opened the drawer again, and removed it, once more, from its place. I went back to the vanity not looking in the mirror. I dropped the bit of scarlet silk near my feet on the rug. I was trembling. It seemed I could scarcely get my breath. I lifted my eyes then again to the figure in the mirror. She was not large, but I thought she might be pretty. But it is hard to be objective about such things. I supposed there could be criteria, of one sort or another, in some place or another, of a somewhat ascertainable, quantitative sort, perhaps what men might be willing to pay for you, but even then they would probably be paying for a spectrum of desirabilities, of which prettiness, per se, might be only one, and perhaps not even the most important. I did not know. I suppose even more important would be what a woman looked like to a given man and what he thought he could do with her, or, seeing her, knew he could do with her. I looked at the figure in the mirror. Her nightgown, ankle length, was of white cotton. It seemed rather demure, or timid, I supposed, but there was little doubt that there was a female, and perhaps a rather attractive one, though, to be sure, that would be a judgment for men to more properly make, within it. There were the stains of tears on the cheeks of the girl facing me in the mirror, I noted. She trembled. Her lips moved. Why was she afraid? At what she saw in the mirror? It was herself, surely. Why should she fear that? I saw she wore a nightgown. I liked that. I did not like pajamas. To be sure, she was perhaps too feminine for a woman in these times, but then there are such women, in spite of all. They are real, and their needs are real. I looked at her. Yes, I thought, she was objectively pretty. There was no doubt about it. To be sure, she might not seem so to a crocodile or a tree but she should seem such to a male of her species, and that was what counted. Yes, that was what counted, objectively. To be sure, he would doubtless wish to see if the rest of her matched her face. Men were like that. They were like traders of horses and breeders of dogs, interested in the whole female. I again regarded the girl in the mirror. Yes, I thought, she was too feminine, at least for these times. This was not the sort of woman wanted in our times. She was like something beautiful stranded on a foreign beach. Surely she belonged in another time or place. She seemed in her hormones and beauty, in her needs, like a stranger flung out of time. There she stood in a world alien to her deepest nature, not a man, and not wanting to be one, a victim of time and heredity, of her genetic depths, of biology and history. How lonely and unbefriended, how frustrated, unfulfilled and doleful she was. How tragic is she indeed, I thought, whom the lies of one" s time fail to nourish. I looked again at the girl in the mirror. Surely she might better have cooked meat in the light of a cave fire, the thongs on her left wrist perhaps marking whose woman she was, or with sistrum and hymns, under the orders of priests, welcomed the grand, redemptive, sluggish flows of the Nile; better she had run barefoot on a lonely Aegean beach, her himation gathered to her knees, a fillet of white wool in her hair, watching for oared ships; better she had spun wool in Crete or cast nets, her robes tied to her waist, off the coast of Asia Minor; better she had broken her dolls and put them in the temple of Vesta; better she had been a silken girl breathless behind the wooden screens of the seraglio or a ragged slut on her knees desperately licking and kissing for coins in the sunlit, dusty streets below; better she had been bartered for a thousand horses in Scythia or led to Jerusalem tied by the hair to a Crusader" s stirrup; better to have been a high-born Spanish lady forced to beg to be the bride of a pirate; better to have been an Irish prostitute, her face slashed by Puritans for following the troops of Charles; better to have been a delicate lady of the Regency carried into Turkish slavery; better to have been a Colonial dame spinning in Ohio, looking up to see her first red master. I put down my head, and shook it. Such thoughts must be put from my mind, I told myself. But the girl stood there, still stood there, in the mirror. She had not left, or fled. How bold she was, or how deep were her needs! I shuddered. How many times I had awakened from sleep, moving against the coarse, narrow cords which had held me down, above and below my breasts and crossed between them, leaving their cruel marks on my body! How many times had I awakened, seeming still to feel the tight bite of cruel shackles on my wrists and ankles.

Читать дальше