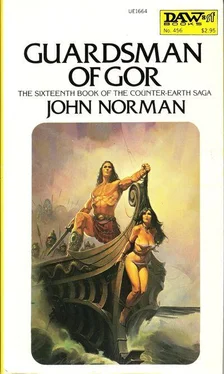

GUARDSMAN OF GOR

(Volume Sixteen of the Chronicles of Counter Earth)

by John Norman

Chapter 1 - SHIPS OF THE VOSKJARD

Most Gorean ships have a concave bow, which descends gracefully into the water. Such a construction facilitates the placing of the ram-mount and ram.

I watched, fearfully, almost mesmerized, as the first of the gray galleys, emerging from the fog, moving swiftly, like a living thing, looming now, struck the chain.

Battle horns sounded about me. I heard them echoed in the distance, the sounds first taken up by the Mira and Talender .

There was a great sound, the hitting of the huge chain by the galley, a sound as of the striking of the chain, and then the grating sound, scraping and heavy, of the chain literally being lifted out of the water. I saw it, fascinated, black, dripping water, glistening, slide up the bow, splintering wood and tearing away paint. Then the whole galley, by its momentum, stopped by the chain, swung abeam. I saw oars snapping.

“The chain holds!” cried Callimachus, elatedly.

Another galley then struck the chain, off the port bow.

“It holds!” cried Callimachus. “It holds!”

I was aware of something moving past me. It was swift. I almost did not register it.

“Light the pitch!” called Callimachus. “Set the catapults! Unbind the javelins! Bowmen to your stations!

I saw, amidships, opposite our galley, on the enemy vessel, two bowmen. They carried the short, stout ship’s bow. They were some forty yards away.

I looked upon them, fascinated.

They seemed unreal. But they were the enemy.

“Down!” called Callimachus. “Protect yourself!”

I crouched behind the bulwarks. I heard again, twice, the slippage of air, sliding and divided, marked by what I now recognized was the passage of slender, flighted wood. One arrow struck into the stem castle behind me and to my left. The sound was firm, authoritative. The other arrow with a flash of sparks struck the mooring cleat on the bulwark to my right and glanced away into the water.

I heard the snap of bow strings on my own vessel, returning the fire.

“Hold your fire!” called Callimachus.

Lifting my head I saw the enemy galley back-oaring on the starboard side, and then, straightened, back-oaring from the chain.

Some fifty yards away I heard another galley strike at the chain.

A cheer drifted across the water. Again, it seemed, the chain had held.

Across the chain I heard signal horns.

Callimachus was now on the height of the stem castle. “Extinguish the pitch!” he called.

I tried to see through the fog. No longer did there seem enemy ships at the chain.

Callimachus, twenty feet above me, his hands on the stern castle railing, peered out into the fog. “Steady!” he called to the two helmsmen, at the rudders. A sudden wind was pulling at the fog. I heard the rudders and rudder-mounts creak. The oar master set the oars outboard, into the water.

“Look!” cried Callimachus. He was pointing to starboard. The wind had torn open a wide rift in the vapors of the fog.

There was a cheer behind me. At the chain, settling back, its concave bow lifted fully from the water, its stern awash, was a pirate galley. Men were in the water. Beyond this ship, too, there was another pirate galley, crippled, listing.

“They will come again!” called Callimachus.

But this time I did not think they would attempt to so brazenly assault the chain.

This time, I speculated, they would attempt to cut it. In such a situation they must be prevented from doing so. They would have to be met at the chain.

“Rations for the men!” called Callimachus. “Eat a good breakfast, Lads,” he called, “for there is work to be done this day!”

I resheathed then the sword. The Voskjard had not been able to break the chain.

It seemed to me then that we might keep him west of the chain. I was hungry.

***

“They are coming, Lads!” called Callimachus from the stem castle.

I went to the bow, to look. The fog now, in the eighth Ahn, had muchly dissipated. Only wisps of it hung still about the water.

“Light the pitch!” called Callimachus. “Be ready with the catapults! Bowmen to your stations!”

In a moment I smelled the smell of burning pitch. It contrasted strongly with the vast, organic smell of the river.

I could see several galleys, some two to three hundred yards away, approaching the chain.

I heard the creak of a catapult, being reset. The bowmen took up their positions behind their wicker blinds.

Here and there, on the deck, there were buckets of sand, and here and there, on ropes, some of water.

I heard the unwrapping and spilling of a sheaf of arrows, to be loose at hand behind one of the blinds. There are fifty arrows in each such sheaf.

A whetstone, somewhere, was moving patiently, repetitively, on the head of an ax.

I saw Callimachus lift his hand. Behind him an officer would relay his signal. On the steps of the stern castle, below the helm deck, the oar master would be watching. The oars were already outboard.

I doubted that any of the enemy galleys would be so foolish as to draw abeam of the chain.

I could not believe my eyes. Was it because the flag of Victoria flew on our stem-castle lines?

I saw the hand of Callimachus fall, almost like a knife. In an instant, the signals relayed, the Tina leaped forward.

It took less than an Ehn to reach the chain. The iron-shod ram slid, grating, over the chain and struck the enemy vessel amidships. The strakes of her hull splintered inward. Men screamed. I had been thrown from my feet in the impact. I heard more wood breaking as we back-oared from the vessel, the ram moving in the wound. I heard water rushing into the other vessel, a rapid, heavy sound. She was stove in. A heavy stone, from some catapult, struck down through the deck near me, fired doubtless from some other galley. A javelin, tarred and flaming, snapped from some springal, thudded into the stem castle. Arrows were exchanged. Then we had backed away, some seventy-five feet from the chain. Some men were clinging to the chain. I heard a man moaning, somewhere behind me. I snapped loose the javelin from the stem castle and threw it, still flaming, overboard.

Here and there, along the chain, we could see other galleys drawing abeam of it, and men, in small boats, with tools, cutting at the great links.

Again, in moments, the hand of Callimachus lifted, and again fell.

Once more the ram struck deep into the strakes of an enemy vessel.

Once more we drew back.

A clay globe, shattering, of burning pitch struck across our deck. Another fell hissing into the water off our starboard side. Our own catapults returned fire, with pitch and stones. We extinguished the fire with sand.

“They will lie to now,” said Callimachus to the officer beside him. “We will be unable to reach them with the ram.”

I could see, even as he spoke, several of the pirate vessels drawing back, abeam of the chain, but far enough behind it to prevent our ram from reaching them. Off our port bow we saw one of the pirate vessels slip beneath the muddy waters of the Vosk, a kill of the Mira .

Small boats again approached the chain.

We edged forward again. A raking of arrows hailed upon our deck, many bristling then, too, in the stem castle.

“Bowmen!” called Callimachus.

We spent a shower of arrows at the nearest longboat. Two men fell from the boat into the water. Other men dove free into the river, swimming back about the bow of the nearest pirate vessel.

“Do not let them near the chain!” called Callimachus to the bowmen.

Читать дальше