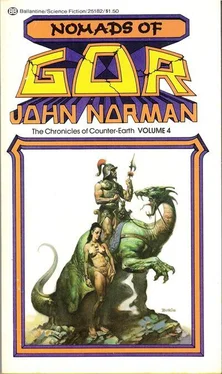

NOMADS OF GOR

(Volume four of the Chronicles of Counter-Earth)

by John Norman

Chapter 1

THE PLAINS OF TURIA

“Run!” cried the woman. “Flee for your life!”

I saw her eyes wild with fear for a moment above the rep-cloth veil and she had sped past me.

She was peasant, barefoot, her garment little more than coarse sacking. She had been carrying a wicker basket containing vulos, domesticated pigeons raised for eggs and meat.

Her man, carrying a mattock, was not far behind. Over his left shoulder hung a bulging sack filled with what must have been the paraphernalia of his hut.

He circled me, widely. “Beware,” he said, “I carry a Home Stone.”

I stood back and made no move to draw my weapon. Though I was of the caste of warriors and he of peasants, and I armed and he carrying naught but a crude tool, I would not dispute his passage. One does not lightly dispute the passage of one who carries his Home Stone.

Seeing that I meant him no harm, he paused and lifted an arm, like a stick in a torn sleeve, and pointed backward. “They’re coming,” he said. “Run, you fool! Run for the gates of Turia!”

Turia the high-walled, the nine-gated, was the Gorean city lying in the midst of the huge prairies claimed by the Wagon Peoples.

Never had it fallen.

Awkwardly, carrying his sack, the peasant turned and stumbled on, casting occasional terrified glances over his shoulder.

I watched him and his woman disappear over the brown wintry grass.

In the distance, to one side and the other, I could see other human beings, running, carrying burdens, driving animals with sticks, fleeing.

Even past me there thundered a lumbering herd of startled, short-trunked kailiauk, a stocky, awkward ruminant of the plains, tawny, wild, heavy, their haunches marked in red and brown bars, their wide heads bristling with a trident of horns; they had not stood and formed their circle, shes and young within the circle of tridents; they, too, had fled; farther to one side I saw a pair of prairie sleen, smaller than the forest sleen but quite as unpredictable and vicious, each about seven feet in length, furred, six-legged, mammalian, moving in their undulating gait with their viper’s heads moving from side to side, continually testing the wind; beyond them I saw one of the tumits, a large, flightless bird whose hooked beak, as long as my forearm, attested only too clearly to its gustatory habits; I lifted my shield and grasped the long spear, but it did not turn in my direction; it passed, unaware; beyond the bird, to my surprise, I saw even a black larl, a huge catlike predator more commonly found in mountainous regions; it was stalking away, retreating unhurried like a king; before what, I asked myself, would even the black larl flee; and I asked myself how far it had been driven; perhaps even from the mountains of Ta-Thassa, that loomed in this hemisphere, Gor’s southern, at the shore of Thassa, the sea, said to be in the myths without a farther shore.

The Wagon Peoples claimed the southern prairies of Gor, from the gleaming Thassa and the mountains of Ta-Thassa to the southern foothills of the Voltai Range itself, that reared in the crust of Gor like the backbone of a planet. On the north they claimed lands even to the rush-grown banks of the Cartius, a broad, swift flowing tributary feeding into the incomparable Vosk. The land between the Cartius and the Vosk had once been within the borders of the claimed empire of Ar, but not even Marlenus, Ubar of Ubars, when master of luxurious, glorious Ar, had flown his tarnsmen south of the Cartius.

In the past months I had made my way, afoot, overland, across the equator, living by hunting and occasional service in the caravans of merchants, from the northern to the southern hemisphere of Gor. I had left the vicinity of the Sardar Range in the month of Se`Var, which in the northern hemisphere is a winter month, and had journeyed south for months; and had now come to what some call the Plains of Turia, others the Land of the Wagon Peoples, in the autumn of this hemisphere; there is, due apparently to the balance of land and water mass on Gor, no particular moderation of seasonal variations either in the northern or southern hemisphere; nothing much, so to speak, to choose between them; on the other hand, Gor’s temperatures, on the whole, tend to be somewhat fiercer than those of Earth, perhaps largely due to the fact of the wind-swept expanses of her gigantic land masses; indeed, though Gor is smaller than Earth, with consequent gravitational reduction, her actual land areas may be, for all I know, more extensive than those of my native planet; the areas of Gor which are mapped are large, but only a small fraction of the surface of the planet; much of Gor remains to her inhabitants simply terra incognita. [1]

For some minutes I stood silently observing the animals and the men who pressed toward Turia, invisible over the brown horizon. I found it hard to understand their terror.

Even the autumn grass itself bent and shook in brown tides toward Turia, shimmering in the sun like a tawny surf beneath the fleeing clouds above; it was as though the unseen wind itself, frantic volumes and motions of simple air, too desired its sanctuary behind the high walls of the far city.

Overhead a wild Gorean kite, shrilling, beat its lonely way from this place, seemingly no different from a thousand other places on these broad grasslands of the south.

I looked into the distance, from which these fleeing multitudes, frightened men and stampeding animals, had come. There, some pasangs distant, I saw columns of smoke rising in the cold air, where fields were burning. Yet the prairie itself was not afire, only the fields of peasants, the fields of men who had cultivated the soil; the prairie grass, such that it might graze the ponderous bosk, had been spared.

Too in the distance I saw dust, rising like black, raging dawn, raised by the hoofs of innumerable animals, not those that fled, but undoubtedly by the bosk herds of the Wagon Peoples.

The Wagon Peoples grow no food, nor do they have manufacturing as we know it. They are herders and it is said, killers. They eat nothing that has touched the dirt. They live on the meat and milk of the bosk. They are among the proudest of the peoples of Gor, regarding the dwellers of the cities of Gor as vermin in holes, cowards who must fly behind walls, wretches who fear to live beneath the broad sky, who dare not dispute with them the open, windswept plains of their world.

The bosk, without which the Wagon Peoples could not live, is an ox like creature. It is a huge, shambling animal, with a thick, humped neck and long, shaggy hair. It has a wide head and tiny red eyes, a temper to match that of a sleen, and two long, wicked horns that reach out from its head and suddenly curve forward to terminate in fearful points. Some of these horns, on the larger animals, measured from tip to tip, exceed the length of two spears.

Not only does the flesh of the bosk and the milk of its cows furnish the Wagon Peoples with food and drink, but its hides cover the domelike wagons in which they dwell; its tanned and sewn skins cover their bodies; the leather of its hump is used for their shields; its sinews forms their thread; its bones and horns are split and tooled into implements of a hundred sorts, from awls, punches and spoons to drinking flagons and weapon tips; its hoofs are used for glues; its oils are used to grease their bodies against the cold. Even the dung of the bosk finds its uses on the treeless prairies, being dried and used for fuel. The bosk is said to be the Mother of the Wagon Peoples, and they reverence it as such. The man who kills one foolishly is strangled in thongs or suffocated in the hide of the animal he slew; if, for any reason, the man should kill a bosk cow with unborn young he is staked out, alive, in the path of the herd, and the march of the Wagon Peoples takes its way over him.

Читать дальше