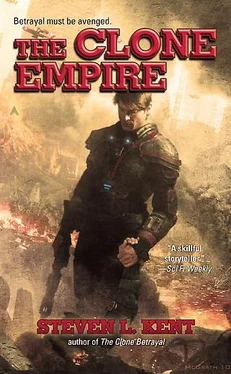

Steven Kent - The Clone Empire

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Steven Kent - The Clone Empire» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Боевая фантастика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Clone Empire

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Clone Empire: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Clone Empire»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Clone Empire — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Clone Empire», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

This time Warshaw acknowledged that his captains had carried out their orders. He then took his frustrations out on the officers who designed the ERP—the “Emergency Response Protocol,” stating that the response times could be cut in half again if the routes were better organized.

All of this came as old news to everyone else in the room; but I had never heard any of it. Until a few weeks ago, I had been safely tucked away on Terraneau worrying about the locals breaking into an underground parking lot. Now I had galactic security on my mind, and spy ships, and infiltrator clones.

When Warshaw’s staff simulated a surprise attack on Olympus Kri, twenty-six fighter carriers and sixty-three battleships arrived on the scene within seventeen minutes. Another fifty ships arrived by the half-hour mark.

As he spoke, I came to realize that Gary Warshaw had morphed into the Napoleon specking Bonaparte of his time. Maybe all clone brains weren’t created equal, I thought. But then again, maybe they were. Maybe the U.A. had accidentally packed two brains into Warshaw’s wide, bald pate.

Standing at the lectern, looking mildly deformed with his hairless head and endless stream of muscles, Warshaw smiled and announced the results of his most recent exercise. Twenty-eight ships had responded to a simulated attack on Gobi within six minutes. Within twenty minutes, fifty-two ships had arrived on the scene.

“You know what that tells me,” Warshaw said. “That tells me that the Enlisted Man’s Navy has the will to survive.”

Applause rose from the audience. Were they applauding themselves for their fast response or Warshaw for working miracles? I didn’t know, and neither did he. I doubt the admirals knew, but they clapped until Warshaw raised his hands, signaling for them to stop. Warshaw’s presentation included charts and holographic displays. It lasted four hours. By the time he finished, it was time for lunch.

I was next on the agenda, right after lunch. With a sinking feeling, I searched the dining hall for Cabot. He was nowhere to be seen.

Not feeling especially hungry, I went to my billet. I called Station Security to see if Cabot had returned. They checked their records and reported that he’d left Gobi Station shortly before the morning session began. He had not yet returned.

I left orders for them to rush Cabot to the summit the moment he passed through security. Even if it meant interrupting a closed session, they were to send him in.

Before rejoining Warshaw and his fleet commanders, I contacted the morgue. Sam had gone home for the day; but Myron, the senior coroner, was there. He gave me some very good news.

I returned to the summit slightly before 13:00, just in time for the meeting to begin. Warshaw stopped at my desk, and said, “I didn’t see you at lunch. I hope you don’t get all weird when you make presentations.”

“Just nailing down a few loose ends,” I said.

“So are you ready to present?” he asked.

I nodded, and he headed to the lectern. Introducing me only as “Harris,” he told the group that I would report about a “special intelligence operation” under my command. He then turned the next session of the meeting over to me.

Not feeling especially nervous, I walked up to the stand. I knew a few of the men, but not many. With the exception of Warshaw, not a one of them had done anything to earn my respect. Their idea of combat involved sitting on the bridge of a carrier while Marines and fighter pilots did the heavy lifting.

I began with a bombshell.

“The Unified Authority is tracking our movements,” I said. I turned to Warshaw, and added, “When you ran that last ERP, you revealed your fleet movements, emergency protocols, and readiness to the Pentagon.”

I doubted there was so much as a single officer in the room who believed me. I was a Marine speaking to Navy men. They trusted me to shoot guns and throw grenades, but they didn’t respect my intelligence-gathering ability any more than I respected their hand-to-hand combat experience.

Repeating the scraps of information I’d learned from Ray Freeman, I continued. “The Unified Authority has set up spy satellites to monitor our broadcast activity. Every time our ships broadcast in or out of an area, those satellites read the anomaly.”

The room went quiet. Men who had originally doubted now began wondering just how much I knew. Spy satellites reading distant anomalies, the technology was basic and nearly impossible to track. Reading anomalies was child’s play, and the data could be synchronized to track the entire empire’s movements.

“Why haven’t we spotted any of their satellites?” one admiral asked. He sounded cynical. I didn’t blame him.

“Have you looked for satellites?” I asked. “We’re talking satellites the size of golf balls floating in millions of miles of open space. What are the odds of finding them?”

That shut him up. There was no point sending ships out to look for the satellites. It would be like combing a ten-mile stretch of beach for one specific grain of sand.

“How are they deploying them?” another admiral asked.

Warshaw stood, and the room went quiet. He asked, “Is that what the cruisers were doing, dropping spy satellites?”

“If we chart the cruisers’ courses, maybe we can find their satellites,” another admiral suggested. The idea had not occurred to me. It touched off a discussion.

As the admirals discussed ways to search for satellites, the door opened, and in walked Admiral Cabot. He stared at me, waited until we had eye contact, gave me a nod, then went to the desk where I’d been seated. I breathed a sigh of relief. The pretentious little bastard would not have come without completing his mission.

An admiral sitting a few tables from Warshaw yelled, “If they really have those satellites, then they’ve analyzed our Emergency Response Protocol.” His voice rose above the din.

“We need to destroy the satellites,” somebody yelled. I did not see who.

“Don’t be in too big a hurry to destroy them,” I said, quieting down the room. I repeated this, and added, “It’s always a good idea to give your enemies a little misinformation before killing their spies.”

A general hush fell over the room as the admirals considered this.

“Misdirection, I like it,” Warshaw said. “Norma ships responding to Orion …Perseus ships covering Sagittarius. Do it right, and we could really speck with their intel.”

With the meeting dissolving into many conversations, I asked Warshaw if he would mind giving me a fifteen-minute break. I used the time to catch up with Cabot.

“We had to go all the way to Terraneau,” he complained.

“What did you find?”

“Their cruisers are built for spying, not combat. They have cloaking equipment, and they’re fast. They have a top speed of thirty-eight million miles per hour.”

Our ships topped out at thirty million.

“So you found one at Terraneau?” I asked.

“Three of ’em. I boarded one myself. It had three landing bays, all kinds of spy gear, and no weapons …just bays and bunks. And the landing bays were big, almost ten thousand square feet of parking space.”

I heard him, but it didn’t sound possible. “Ten thousand feet per bay?”

He nodded.

I considered the ramifications, and said, “Oh, shit.”

CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX

I started the meeting with another explosion.

“I caught the assassin who killed Admiral Franks,” I began. It was sort of true. Whoever killed Lilburn Franks, his DNA would be identical to Philip Sua’s DNA. His chromosomes would match as well.

Firing a gun into the ceiling would not have captured their attention as quickly. From the moment an aide had found Thorne’s and Franks’s bodies, these men had been living in fear. With the Unifieds killing top officers, every man in the room was a target.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Clone Empire»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Clone Empire» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Clone Empire» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.