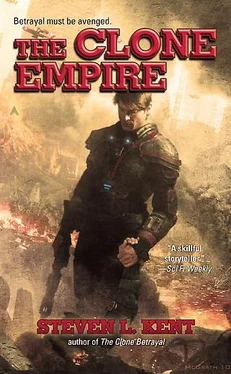

Steven Kent - The Clone Empire

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Steven Kent - The Clone Empire» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Боевая фантастика, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Clone Empire

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Clone Empire: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Clone Empire»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Clone Empire — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Clone Empire», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I asked her if she would be willing to present this information to the admirals during the afternoon session, and she said that would be fine. With the pieces of the puzzle she had given me, I finally understood the infiltrators. What the coroners found was good. What she uncovered was gold.

“They built his brain with a slight abnormality,” Dr. Morman told me. She sat on her rolling stool, I stood. We were still in the lab, close enough for Sua to overhear our conversation.

“You said that Myron and Sam told you about the slowed activity level in the dead clone’s frontal lobe.”

I nodded.

“It’s a symptom of BPD, Borderline Personality Disorder. It’s not uncommon …well, not among clones, it’s not. Mr. Sua is something of an extreme case.”

I got as far as, “I don’t understand. What is Borderline Personality—” but she interrupted me.

“Borderline Personality Disorder. It’s a neurophysiological condition that interferes with the patient’s ability to regulate emotion. It affects the way they interpret social questions. If someone told you or me that we had lint on our clothing or a smudge on our face, we’d go clean up and not give it a second thought. It’s a normal interaction, something you fix and forget.

“Someone like Mr. Sua would take it as a personal affront.”

“So he’s crazy,” I said.

“Not crazy.”

“And you think the Unified Authority purposely made him this way?” I asked.

“The tissue from the clone in the morgue suggests he had the same disorder.” Dr. Morman took a long look at Sua, then turned back to me, and said, “Judging by the NAA samples, he was an extreme case as well.”

“Why in the world would the Unified Authority want an army of pathologically insecure clones?” I asked.

Dr. Morman took a deep breath, then spoke in a whisper. “People with BPD have a nearly debilitating fear of abandonment. If his superiors threatened him, maybe told him to kill you or they would give him a dishonorable discharge, Sua would see you as the cause of all his fears. He’d rather die than have his superiors abandon him.”

“Okay, that explains Lewis’s behavior,” I said. When Dr. Morman gave me a funny look, I said, “The one in the morgue.

“But Sua didn’t put up a fight at all. I came unarmed, and he surrendered.”

“I asked him about that. He said you caught him off guard when you came in unarmed and alone,” said Dr. Morman. “BPD creates a fascinating dichotomy. Patients have a false sense of confidence. In extreme cases, like Sua’s, the patient thinks of himself as undefeatable. He had unreasonable overconfidence; but once you challenged that confidence, he was crushed. He said you disarmed him the first time he attacked you.”

“The only time he attacked me,” I said.

“Right. The second time you found him, you came in alone and unarmed, and that made him believe that you had no fear of him. When you treated him like a helpless child, he decided he did not stand a chance against you and gave up.”

“So he’s useless,” I said.

“So he’s dangerous,” Dr. Morman corrected me. “This man hates you. He has personalized his fight with you. If he were to get free, he would dedicate his life to destroying you, and he would find a way to do it.

“And something else, he feels that way about the entire Enlisted Man’s Empire. He believes you and the other clones left him behind on Earth to die.”

“That’s ridiculous,” I said.

“General, it’s not ridiculous to him. That is how he interprets information. He’s not just an enemy soldier, not just some kind of spy; because of his built-in insecurities, this man takes every offense as if it were personal. He is strong, he is intelligent, and he is willing to dedicate his life to your destruction.

“If you’re not worried by an enemy like that …” She shook her head. “You are a Liberator. Everyone knows what you are capable of doing; but I would hate to have someone like him hunting me, General Harris.”

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE

During breakfast, I gave Admiral Cabot an assignment. We sat alone at a small table in a corner of the mess. I was tired from my early-morning meeting with the forensic psychologist. He looked well rested.

“I need you to do something,” I said as I downed my third cup of coffee. “I need you to get me some information about cruisers.”

Cabot put down his coffee and pulled out his notepad. “What are you looking for?” he asked.

“I need to know about landing bays on cruisers.”

“Okay, what about the landing bay?” he asked. He sounded confident, like he already had the answers.

“The measurements. I need to know the number of bays and the square footage.”

“One bay, it holds four transports. I’d put it at three thousand square feet, not including the tunnel.”

He leaned forward, put up a hand as if blocking outsiders from overhearing what he had to say next, and added, “I spent three years on a cruiser.”

“Not our cruisers,” I said. “Theirs. I need to know about the new ones, the cruisers the Unifieds have been using to spy on us.”

“Oh.” Cabot sounded disappointed. He knew I wanted the information right away, and that meant missing part of the summit. I was getting in the way of his ass-kissing and politicking; and from his expression, I could tell that he resented it.

“You can start by going to Navy Intel; you might get lucky,” I said.

“What if they don’t have the information?” he asked.

“Then fly out to the ad-Din and have Villanueva take you to Terraneau. There’s all kinds of wreckage floating around out there; you’re bound to find a cruiser.”

“You want me to measure a wreck? How am I supposed to do that?”

“I don’t care if you use your dick, just get me the specking dimensions. You got that?”

It was crude talk, but I needed to get through to him. As we spoke, Cabot sat there watching the other admirals enter the briefing room. I could read his thoughts. He wanted to pawn the assignment off on an underling. He wanted to be in the summit rubbing shoulders with the two-stars.

“By the way, don’t use your dick,” I said. “You’re going to need something longer.” And something that doesn’t change size every time a superior officer walks past, I thought.

“Aye, aye, sir,” he said, barely trying to disguise the snarl in his voice.

I had my reasons for wanting Cabot to handle this himself. Like him or hate him, J. Winston Cabot got things done. When I gave him orders, he executed them as if his next promotion depended on it. The information he brought me would check out; and since he would not be able to enter the summit until he got those dimensions, he’d be fast.

“You better get going, Admiral,” I said. “I’m presenting this afternoon. I need that information before I start my presentation.”

“Yes, sir,” he said. He took one last fawning look at the door to the summit, then put down his coffee and headed off.

The morning’s meetings went quickly. We discussed fleet readiness. Warshaw had run a series of drills to test how quickly he could shift forces to meet an invasion. When he simulated an attack on the Golan Dry Docks in his first exercise, only six fleets responded. While the first ships arrived in thirteen minutes, the bulk took between forty minutes and an hour. The final three ships to arrive on the scene did not broadcast in for three hours.

Heads rolled. High-ranking officers were offered early retirements. Rumor had it that one man shot himself rather than face Warshaw’s wrath.

The next fire drill went better. It took less than ten minutes for the first few carriers to arrive. The entire armada broadcasted in within fifty minutes. Some of those ships went through four broadcast transfers, traveling as many as eighty-three thousand light-years to arrive on the scene.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Clone Empire»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Clone Empire» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Clone Empire» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.