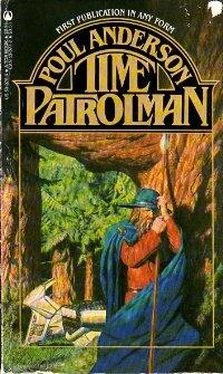

Poul Anderson - The Sorrow of Odin the Goth

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Poul Anderson - The Sorrow of Odin the Goth» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1983, ISBN: 1983, Издательство: Tor, Жанр: Альтернативная история, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Sorrow of Odin the Goth

- Автор:

- Издательство:Tor

- Жанр:

- Год:1983

- ISBN:0-812-53076-4

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Sorrow of Odin the Goth: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Sorrow of Odin the Goth»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Sorrow of Odin the Goth — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Sorrow of Odin the Goth», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

What I said about, say, the Romans merely added detail to information they already had from travelers; and those details would shortly be garbled down to the general noise level of their concepts of Rome. As for more exotic material, well, what was somebody like Cuchulainn but one more foredoomed hero, such as they’d heard scores of yarns about? What was the Han Empire but one more fabulous country beyond the horizon? My immediate listeners were impressed; but afterward they passed it on to others, who merged everything into their existing sagas.”

Everard nodded. “M-m-m-hm.” He smoked for a bit. Abruptly: “What about yourself? You’re not a clutch of words; you’re a concrete and enigmatic person who keeps appearing among them. You propose to do it for generations. Are you setting up in business as a god?”

That was the hard question, for which I’d spent considerable time preparing. I let another swallow of my drink glow down my throat and warm my stomach before I replied, slowly: “Yes, I’m afraid so. Not that I intended it or want it, but it does seem to have happened.”

Everard scarcely stirred. Lazily as a lion, he drawled, “And you maintain that doesn’t make a historical difference?”

“I do. Please listen. I’ve never claimed to be a god, or demanded divine prerogatives, or anything like that. Nor do I propose to. It’s just come about. In the nature of the case, I arrived alone, dressed like a wayfarer but not like a bum. I carried a spear because that’s the normal weapon for a man on foot. Being of the twentieth century, I’m taller than the average for the fourth, even among Nordic types. My hair and beard are gray. I told stories, described distant places, and, yes, I did fly through the air and strike terror into enemies—It couldn’t be helped. But I did not, repeat not establish a new god. I merely fitted an image they’d long worshipped, and in the course of time, a generation or so, they came to assume I must be him.”

“What’s his name?”

“Wodan, among the Goths. Cognate to western German Wotan, English Woden, Frisian Wons, et cetera. The late Scandinavian version is best known: Odin.”

I was surprised to see Everard surprised. Well, of course the reports I filed with the guardian branch of the Patrol were much less detailed than the notes I was compiling for Ganz. “Hm? Odin? But he was one-eyed, and the boss god, which I gather you are not.… Or are you?”

“No.” How soothing it was to get back into lecture gear. “You’re thinking of the Eddie, the Viking Odin. But he belongs to a different era, centuries later and hundreds of miles northwestward.

“For my Goths, the boss god, as you put it, is Tiwaz. He goes straight back to the old Indo-European pantheon, along with the other Anses, as opposed to aboriginal chthonic deities like the Wanes. The Romans identified Tiwaz with Mars, because he was the war god, but he was much else as well.

“The Romans thought Donar, whom the Scandinavians called Thor, must be the same as Jupiter, because he ruled over weather; but to the Goths, he was a son of Tiwaz. Likewise for Wodan, whom the Romans identified with Mercury.”

“So mythology evolved as time passed, eh?” Everard prompted.

“Right,” I said. “Tiwaz dwindled to the Tyr of Asgard. Little memory of him was left, except that it was he who’d lost a hand in binding the Wolf that shall destroy the world. However, ‘tyr’ as a common noun is a synonym in Old Norse for ‘god.’

“Meanwhile Wodan, or Odin, gained importance, till he became the father of the rest. I think—though this is something we have to investigate someday—I think that was because the Scandinavians grew extremely warlike. A psycho-pomp, who’d also acquired shamanistic traits through Finnish influence, was a natural for a cult among aristocratic warriors; he brought them to Valhalla. At that, Odin was most popular in Denmark and maybe Sweden. In Norway and its Icelandic colony, Thor loomed larger.”

“Fascinating.” Everard gusted a sigh. “So much more to know than any of us will ever live to learn… Well, but tell me about your Wodan figure in fourth-century eastern Europe.”

“He still has two eyes,” I explained, “but he already has the hat, the cloak, and the spear, which is really a staff. You see, he’s the Wanderer. That’s why the Romans thought he must be Mercury under a different name, same as they thought the Greek god Hermes must be. It all goes back to the earliest Indo-European traditions. You can find hints of it in India, Persia, the Celtic and Slavic myths—but those last are even more poorly chronicled. Eventually, my service will—

“Anyhow. Wodan-Mercury-Hermes is the Wanderer because he’s the god of the wind. This leads to his becoming the patron of travelers and traders. Faring as widely as he does, he must have learned a great deal, so he likewise becomes associated with wisdom, poetry… and magic. Those attributes join with the idea of the dead riding on the night wind—they join to make him the Psycho-pomp, the conductor of the dead down to the Afterworld.”

Everard blew a smoke ring. His gaze followed it, as if some symbol were in its twistings. “You’ve gotten latched onto a pretty strong figure, seems,” he said low.

“Yes,” I agreed. “Repeat, it was none of my intention. If anything, it complicates my mission without end. And I’ll certainly be careful. But… it is a myth which already existed. There were countless stories about Wodan’s appearances among men. That most were fable, while a few reflected events that really happened—what difference does it make?”

Everard drew hard on his pipe. “I dunno. In spite of my study of this episode, as far as it’s gone, I don’t know. Maybe nothing, no difference. And yet I’ve learned to be wary of archetypes. They have more power than any science in history has measured. That’s why I’ve been quizzing you like this, about stuff that should be obvious to me. It isn’t, down underneath.”

He did not so much shrug as shake his shoulders. “Well,” he growled, “never mind the metaphysics. Let’s settle a couple of practical matters, and then get hold of your wife and my date and go have fun.”

337

Throughout that day, battle had raged. Again and again had the Huns dashed themselves over the Gothic ranks, like storm-waves that break on a cliff. Their arrows darkened the sky ere lances lowered, banners streamed, earth shook to the thunder of hoofs, and the horsemen charged. Fighters on foot, the Goths stood fast in their arrays. Pikes slanted forward, swords and axes and bills gleamed at the ready, bows twanged and slingstones flew, horns brayed. When the shock came, deep-throated shouts made answer to the yelping Hunnish war-cries.

Thereafter it was hew, stab, pant, sweat, kill, die. When men fell, feet as well as hoofs crushed rib cages and trampled flesh to red ruin. Iron dinned on helmets, rattled on ringmail, banged the wood of shields and the hardened leather of breastplates. Horses wallowed and shrieked, throats pierced or hocks hamstrung. Wounded men snarled and sought to thrust or grapple. Seldom was anybody sure whom he had struck or who had smitten him. Madness filled him, took him unto itself, whirled black through his world.

Once had the Huns broken an enemy line. They yelled their glee as they reined mounts around to butcher from behind. But as if out of nowhere, a fresh Gothic troop rolled upon them, and now it was they who were trapped. Few escaped. Otherwise, Hunnish captains who saw a charge fail would sound the retreat. Those riders were well drilled; they pulled out of bowshot, and for a while the hosts breathed hard, slaked thirst, cared for their hurt, glared across the ground between.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Sorrow of Odin the Goth»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Sorrow of Odin the Goth» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Sorrow of Odin the Goth» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.