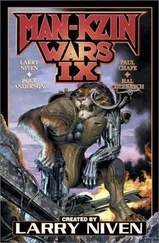

Larry Niven

The Man-Kzin Wars 09

Close to noon, the Father Sun baked pungencies out of turf and turned the forest that walled the northern horizon into a wind-whispery surf of leaves and shadow. Closer by, a field of hsakh stood golden. Kdatlyno slaves were hand-cultivating it in the ancient way, growing fiber that would be handwoven into cloaks for the mighty to wear at Midwinter Bloodfeast and then burn. Scattered elsewhere were the dwellings of the Heroes attendant upon this household. Though stately enough, they were dwarfed by the manor looming ahead of Ghrul-Captain.

These lands were a minor holding of Grand Lord Narr-Souwa's and the building was fairly new, in a modern style. Mosaic of red-and-black thunderbolt pattern decorated walls that sheered up to steep roofs of copper kept blindingly polished, whose beam ends gaped in the forms of carnivores. Tradition had made the lower windows mere gun slits, but those on upper floors were arrogantly broad. Saw-toothed spires at the four cardinal points flew ancestral banners.

As was fitting, Ghrul-Captain had come afoot, unaccompanied, from a landing field now out of sight. But he loped like a warrior to battle and passed the gate with head high. A display of fearlessness also behooved him, showing him not unworthy to enter the presence of the one who waited here.

His hopes heightened when he received due courtesy in return. A pair of armed Heroes met him, gave greeting, and escorted him down a granite corridor to an elevator, and thence to a flamewood door that recognized them and slid aside. There they left him. Ghrul-Captain stepped through. The door silently slid shut at his back.

The chamber was austere, paneled with various metals, its floor turf-like and sound-absorbent. Two open windows let in daylight and summer air. He glimpsed a hookbeak at hover outside. Furnishings were scant, mostly a minimum of communications equipment. He was alone with Narr-Souwa.

That Grand Lord half-reclined on a couch, like a slashtooth at its ease between hunts. He bore no weapons other than his teeth and claws. His only ornament was a scarf loosely draped across a frame whose black-striped orange fur was getting grizzled, but the scarf was of genuine silk, somehow brought from Earth itself. His eyes smoldered yellow, undimmed by the years.

Ghrul-Captain did not simply come to attention and salute, as he would before an ordinary superior. First he lowered his head and knees, tail between thighs. That galled him. It was meant to, he knew. He should think of it as a test. The sword blade, bent, will spring back to keen-edged straightness and ring as it does, if the steel be true.

“Ghrul-Captain of the Navy begs leave to present himself.” The request sounded flat in his ears.

Narr-Souwa peered at him for a while that grew long. “You may relax,” he answered at last. “This interview is at your plea. Justify yourself.”

Ghrul-Captain had rehearsed in his mind. “As my lord knows, I advanced my proposal ”—he laid a measured weight on that word—“through proper channels. I never looked for response at this exalted level, and still less the glory of a flesh-meeting.” Which might , he thought, be the prelude to a death sentence. If so, may I be turned loose in yonder forest for him and his hunters to chase down as they would any other brave, dangerous animal. Maybe I can take one or two to the Darkness with me .

“I want to get the actual scent of you and the sense of how your blood runs,” explained Narr-Souwa. “Yours is an unusual suggestion… especially from a member of your house.”

I have nothing to gain, much to lose, by self-abasement , Ghrul-Captain knew. “Noble One, my wish is to redeem the honor of that house.”

Narr-Souwa stroked his chin. “Honor has been satisfied. High Admiral Ress-Chiuu made a decision and issued orders that proved disastrous. It cost us a warship's whole complement. Worse, it let that ship fall into the hands of the humans. Their naval intelligence has surely been dissecting it ever since. When condemned, Ress-Chiuu went boldly into the Patriarchal Arena and acquitted himself well against the beasts. It was good sport.”

Ghrul-Captain drew breath. “So their spokesmales have graciously informed his kin. But, sire—my lord will understand that we want to make full redemption.”

Narr-Souwa's eyes narrowed a bit. “And thus regain his holdings, as well as the prestige,” he said shrewdly. “The database has told me that you would inherit his estate in the Hrungn Valley.”

For an instant the memory and the yearning stabbed Ghrul-Captain, lands broad beneath the Mooncatcher Mountains, castle raised in olden days when kzin fought kzin hand-to-hand, graves of his forebears, a wilderness to rove in freedom. He curbed himself. “My lord is wise. But I wish yet more to win back the trust, the favor, that raises to leadership.”

He had kept the title to his half-name, but been relieved of command over the Venomous Fang that had been his. Small she was, but swift, agile, deadly. Ah-hai, the beautiful guns and missiles, the standing among his peers and over his crew, the tautness of close maneuver, and space, space, the stars for a hunting ground! “More than life do I want to take a real part in the next war,” and gain repute, a whole name, the right to breed.

Narr-Souwa folded his ears a bit, unfolded them again and murmured, “So you expect a second war with the humans?”

“Doesn't everyone, sire?”

Contempt spat. “ They hope otherwise. Most of them.”

Ghrul-Captain deemed it best to wait.

The Grand Lord sighed. “We need time to make ready, time. The more so after that major setback at the ancient red sun. This later affair at the black hole was less catastrophic, but—it has doubtless changed the minds of still more monkeys about us. Certainly they now have important data on our Raptor-class ships.”

“With deepest respect, sire,” Ghrul-Captain ventured, “I submit that we should not let them gather information we do not even possess.”

“Hr-r-r, yes. That expedition they are planning, to the young sun and its doomed planet. Well, but what intelligence we have on it inclines me to believe it will be what they claim, purely scientific .” Perforce Narr-Souwa spoke that phrase in the closest rough, snarling approximation to English the kzin voice could manage, for nothing quite like it existed in any language of his race.

Here was a moment to show initiative and thoughtfulness. “Monkey curiosity, sire. I took this into account. They are—no, not so much flighty as… playful. The most playful breed in known space. The oldest of them are like kittens.”

“Kittens that never grow up to realism or dignity. Vermin of the universe… But how does this little new game of theirs concern us?”

“Sire, I tried to make that clear in my petition. They suppose they may learn something they do not yet know. What that might be, they do not know either. It may well prove of no practical value. Nevertheless, my lord, those monkeys have a way of turning anything into a weapon if they feel the need. Anything.”

And thus they beat back our invasion , Ghrul-Captain recalled, and were the first to acquire the hyperdrive, and stuffed what they snivel is peace down our throats . He nearly gagged.

“Granted.” Narr-Souwa's eyes seemed to kindle. His whiskers lifted, his voice dropped to a purr. “Do you imply the Supreme Councillors have not studied the enemy's history?”

“Of course not, Grand Lord,” Ghrul-Captain protested. “Never!” Boldness was advisable, within bounds. “Still, sire, they have much to think upon, many spoor to trace. I merely offer them an idea.”

Читать дальше