Kim Stanley Robinson

Antarctica

“The land looks like a fairytale.”

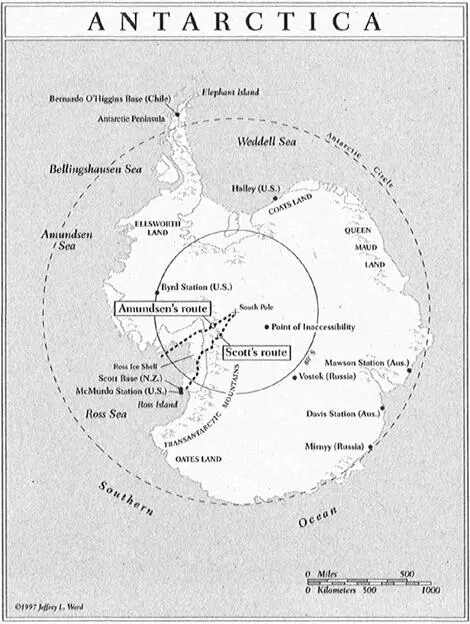

—ROALD AMUNDSEN

First you fall in love with Antarctica, and then it breaks your heart.

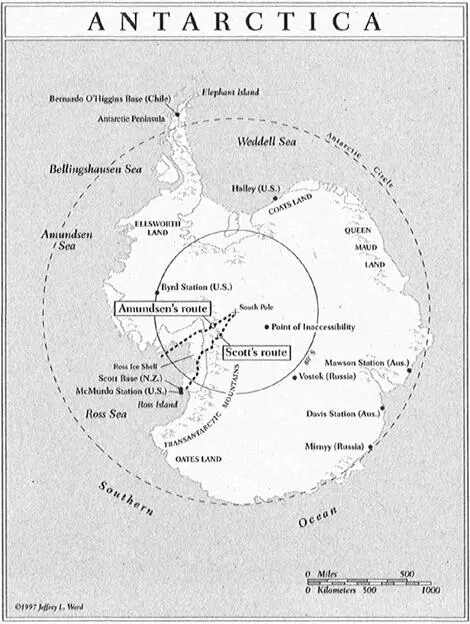

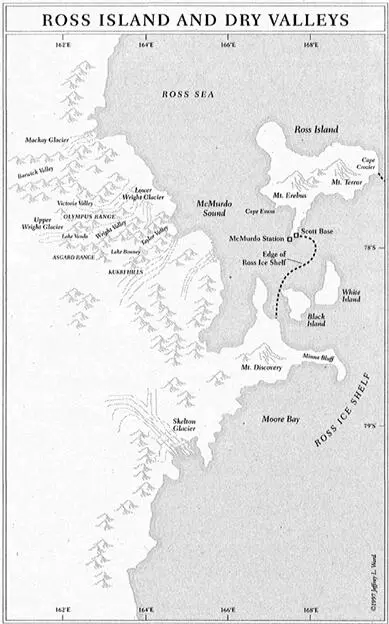

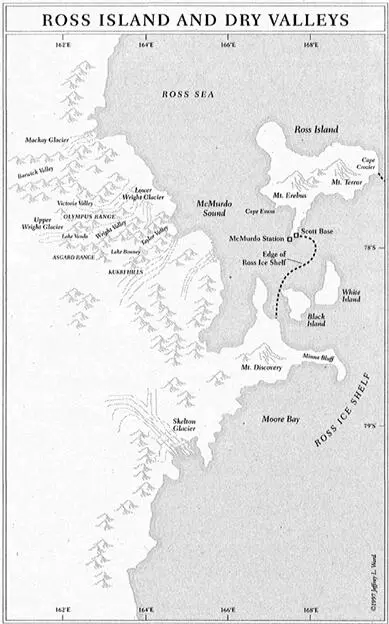

Breaks it first in all the usual sorry ways of the world, sure—as for instance when you go down to the ice to do something unusual and exciting and romantic, only to find that your job there is in fact more tedious than anything you have ever done, janitorial in its best moments but usually much less interesting than that. Or when you discover that McMurdo, the place to which you are confined by the strictest of company regulations, resembles an island of traveler services clustered around the offramp of a freeway long since abandoned. Or, worse yet, when you meet a woman, and start something with her, and go with her on vacation to New Zealand, and travel around South Island with her, the first woman you ever really loved; and then after a brief off-season you return to McMurdo and your reunion with her only to have her dump you on arrival as if your Kiwi idyll had never happened. Or when you see her around town soon after that, trolling with the best of them; or when you find out that some people are calling you “the sandwich,” in reference to the ice women’s old joke that bringing a boyfriend to Antarctica is like bringing a sandwich to a smorgasbord. Now that’s heartbreak for you.

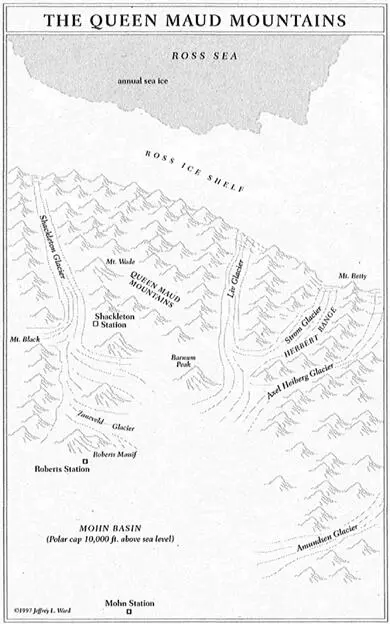

But then the place has its own specifically Antarctic heartbreaks as well, more impersonal than the worldly kinds, cleaner, purer, colder. As for instance when you are up on the polar plateau in late winter, having taken an offer to get out of town without a second thought, no matter the warnings about the boredom of the job, for how bad could it be compared to General Field Assistant? And so there you are riding in the enclosed cab of a giant transport vehicle, still thinking about that girlfriend, ten thousand feet above sea level, in the dark of the long night; and as you sit there looking out the cab windows, the sky gradually lightens to the day’s one hour of twilight, shifting in invisible stages from a star-cluttered black pool to a dome of glowing indigo lying close overhead; and in that pure transparent indigo floats the thinnest new moon imaginable, a mere sliver of a crescent, which nevertheless illuminates very clearly the great ocean of ice rolling to the horizon in all directions, the moonlight glittering on the snow, gleaming on the ice, and all of it tinted the same vivid indigo as the sky; everything still and motionless; the clarity of the light unlike anything you’ve ever seen, like nothing on Earth, and you all alone in it, the only witness, the sole inhabitant of the planet it seems; and the uncanny beauty of the scene rises in you and clamps your chest tight, and your heart breaks then simply because it is squeezed so hard, because the world is so spacious and pure and beautiful, and because moments like this one are so transient—impossible to imagine beforehand, impossible to remember afterward, and never to be returned to, never ever. That’s heartbreak as well, yes—happening at the very same moment you realize you’ve fallen in love with the place, despite all.

Or so it all happened to the young man looking out the windows of the lead vehicle of that spring’s South Pole Overland Traverse train—the Sandwich, as he had been called for the last few weeks, also the Earl of Sandwich, the Earl, the Duke of Earl (with appropriate vocal riff), and the Duke; and then, because these variations seemed to be running thin, and appeared also to touch something of a sore spot, he was once again referred to by the nicknames he had received in Antarctica the year before: Extra Large, which was the size announced prominently on the front of his tan Carhartt overalls; and then of course Extra; and then just plain X. “Hey X, they need you to shovel snow off the coms roof, get over there!”

After the sandwich variations he had been very happy to return to this earlier name, a name that anyway seemed to express his mood and situation—the alienated, anonymous, might-as-well-be-illiterate-and-signing-his-name-with-a-mark General Field Assistant, the Good For Anything, The Man With No Name. It was the name he used himself—“Hey Ron, this is X, I’m on the coms roof, the snow is gone. What next, over.”—thus naming himself in classic Erik Erikson style, to indicate his rebirth and seizure of his own life destiny. And so X returned to general usage, and became again his one and only name. Call me X. He was X.

* * *

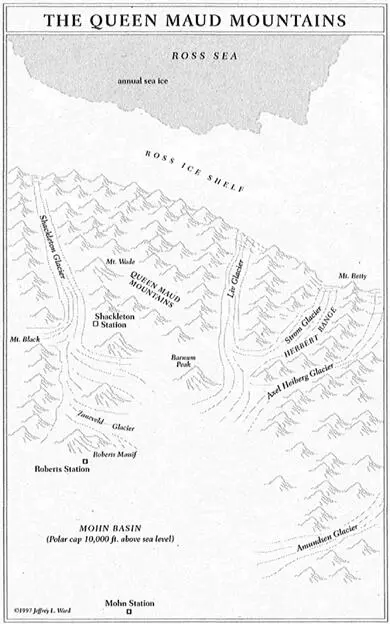

The SPOT train rolled majestically over the polar cap, ten vehicles in a row, moving at about twenty kilometers an hour—not bad, considering the terrain. X’s lead vehicle crunched smoothly along, running over the tracks of previous SPOT trains, tracks that were in places higher than the surrounding snow, as the wind etched the softer drifts away. The other tractors were partly visible out the little back window of the high cab, looking like the earthmovers that in fact had been their design ancestors. Other than that, nothing but the polar plateau itself. A circular plain of whiteness, the same in all directions, the various broad undulations obscure in the starlight, obvious in the track of reflected moonlight.

As the people who had warned him had said, there was nothing for him to do. The train of vehicles was on automatic pilot, navigating by GPS, and nothing was likely to malfunction. If something did, X was not to do anything about it; the other tractors would maneuver around any total breakdowns, and a crew of mechanics would be flown out later to take care of it. No—X was there, he had decided, because somebody up in the world had had the vague feeling that if there was a train of tractors rolling from McMurdo to the South Pole, then there ought to be a human being along. Nothing more rational than that. In effect he was a good-luck charm; he was the rabbit’s foot hanging from the rearview mirror. Which was silly. But in his two seasons on the ice X had performed a great number of silly tasks, and he had begun to understand that there was very little that was rational about anyone’s presence in Antarctica. The rational reasons were all just rationales for an underlying irrationality, which was the desire to be down here . And why that desire? This was the question, this was the mystery. X now supposed that it was a different mix of motives for every person down there—explore, expand, escape, evaporate—and then under those, perhaps something else, something basic and very much the same for all—like Mallory’s explanation for trying to climb Everest: because it’s there. Because it’s there! That’s reason enough!

And so here he was. Alone on the Antarctic polar plateau, driving across a frozen cake of ice two miles thick and a continent wide, a cake that held ninety-five percent of the world’s fresh water, etc. Of course it had sounded exciting when it was first mentioned to him, no matter the warnings. Now that he was here, he saw what people had meant when they said it was boring, but it was interesting too—boring in an interesting way, so to speak. Like operating a freight elevator that no one ever used, or being stuck in a movie theater showing a dim print of Scott of the Antarctic on a continuous loop. There was not even any weather; X traveled under the alien southern constellations with never a cloud to be seen. The twilight hour, which grew several minutes longer every day, only occasionally revealed winds, winds unfelt and unheard inside the cab, perceptible to X only as moving waves of snow seen flowing over the white ground.

Читать дальше