Jaspers reported for duty an hour early. The shift went without surprises. At first he was disconcerted by the squeak of his own boots and of the strap of the uniform, but he grew to like the sound. He didn’t need to raise his voice once. Koleh, on duty with Jaspers for the initiation, said that it went very well, that Jaspers was perhaps even too formal and correct. It was meant as a compliment, not criticism.

“Now, Jaspers, you are a different breed of man,” said Tyang, sitting at the table and sipping herbal tea for his ulcers. “You’ll move to Lauhl but remain a guard. Once a guard, always a guard. The workers mustn’t know that, otherwise everything would fall apart. Those who precede must build for those who follow…”

“How do you know this, Tyang?” asked Lasaille. He lay on his bunk, hands clasped behind his head. “We could get to Lauhl and find everything in ruins there, because people might think that if they’re moving on, there’s no reason to leave anything of value behind…”

“There is no ‘we’ and ‘they’ here,” Tyang returned. “Each person changes Land as an individual and finds the world as it is, and therefore nothing unravels. You serve your eight years and nine months and move on.”

“A generation of destroyers would be a catastrophe,” said Jaspers. “After them, no one would be able to rebuild. A man who wanted to build would know that where he was going he would find only destruction, that if he built, he would leave behind work that had only just begun, with no certainty that those who followed him would continue it… Once destroyed, the social mechanism cannot be re-created.”

“And yet someone created it,” said Dub.

They fell silent, struck not only by the truth of this statement but also by the fact that Dub had spoken.

“I always fear what I will find in the next place,” said Lasaille, breaking the silence.

“Always with the same fear?” asked Tyang.

“Yes.”

“I think that any overturning of a world’s system is impossible. The destroyer would have to be a superior individual, and all such individuals are pulled out to serve as guards. You have a recent example right here… but all of us are examples. No man will bring down a system in which he advances. It would make no sense.”

“I don’t like moving. I never know how much time I will lose in the journey,” muttered Lasaille.

“Sometimes it seems to me that the whole social contract hangs by a thread, and that it is only thanks to us that everything hasn’t gone to hell.”

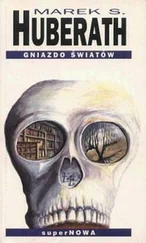

“The Nest of Worlds books depict Lands that are coming apart,” said Jaspers. “The more you read, the more things crumble… People leave their homes, wander like nomads… They don’t build, don’t renew. They have lost faith in what they do.”

“The stunted descendants of giants?” Tyang said, with a whistling s. He had had a tooth pulled recently, and a false one hadn’t been put in yet.

Lasaille shook his head. “No. There were never giants. It’s simply that each book begins with the situation given it. The created world changes according to its own laws. And it moves toward decay.”

“Always?” asked Jaspers.

Lasaille shrugged. “I don’t know. You’ve seen yourself how slowly the reading goes. Perhaps, ultimately, a kind of equilibrium is achieved, imposed by the conditions given, and the future stabilizes.”

“I think,” said Tyang, summing up, “that the Nest of Worlds books are telling us not to throw away what we have.”

Jaspers walked the hall with the regulation spring in his step that he had successfully made a habit. He smacked his black-gloved hand with his stick. He liked to accentuate his presence in this way. The rhythmic smacking could be heard over the roar of the machines, if one was listening for it. Jaspers noted that for a while now the workers, seeing him, appeared to exert less effort, as if slacking. There were half smiles. Or at least he received this impression.

One worker in particular, young and slender, had a sharp look that seemed to unmask Jaspers, to see through the mesh that covered his face and held the sewn microphone, and through the dummy polyurethane muscles as well. Jaspers didn’t like him. The man was sitting at the conveyor belt now with his back to Jaspers, screwing lids on jars as if his hands were two clubs of wood. Jaspers was certain the slacker—safe in the belief that there was no guard nearby—was ridiculing the discipline of the task, feeling not the least respect.

In an instant he was at his side. The others were unable, or didn’t dare, to warn the worker. In one well-trained motion Jaspers dealt the required blow to the small of the back. The man groaned and slid to the ground gasping. His mouth foamed, and he began to twitch convulsively. The other workers murmured, and some even stopped what they were doing.

Jaspers didn’t lose his composure. Calmly, speaking into the microphone of his mask, he summoned medical assistance for the damaged worker.

Because the murmuring continued, he spread his legs per regulations and took a deep breath.

“Attention!” he bellowed.

They all stood at attention. The situation was under control.

“Back to your seats! Back to work!” The commands sealed his victory.

“Have a seat, Mr. Jaspers.” Hullic was unexpectedly friendly and direct. “Do you smoke?”

Jaspers declined. The recent events flew through his head. What had happened was an accident, his striking the worker too hard in the hall, the man now permanently paralyzed. The first time he struck a worker, and it was too hard. He wouldn’t do that again. He would practice carefully to get the force of the blow right. Yes, this would be the only line to take against the chief’s anger.

“As you know, I’m moving to Lauhl,” Hullic began.

Too bad, thought Jaspers. For all his faults, he’s been a good chief.

“I must choose a successor,” Hullic went on. “Which puts me in some difficulty…”

True, thought Jaspers. Lasaille would be the best, but he’s moving too. It’s the old man’s problem, though, not mine… But he was flattered that the commandant was soliciting his advice.

“… and the candidates I might consider, they are also all leaving Taayh in the near future. It makes no sense to appoint someone for a few months.”

Jaspers swallowed.

“So I have decided that you are the best choice. Your excellent reports, your intelligence. And you will be in Taayh for another two and a half years. What do you think?”

“Well, first of all, I’m too young,” said Jaspers, managing to collect himself. He wasn’t eager to advance so quickly. It would antagonize his colleagues. “Secondly, you must be aware of that incident in the hall… I unintentionally crippled a worker. He’s in the hospital because of me.”

Hullic waved that away. “Cedar?” he said. “I inquired about him. He can move his arms now. He’ll be able to work in a sitting position. It was an accident. And your age is not important. Do you agree to take over my duties as commandant?”

“Yes, sir,” said Jaspers, hesitating no longer, but in his heart he wasn’t sure he had made the right decision.

Jaspers was extremely busy. The duties of commandant, it turned out, were difficult and exhausting. He sat at his desk until late. The operation of the food factory, responsible for feeding many thousands of people, was of the utmost importance to Taayh. This fact kept him going, was sufficient reward for his efforts. He recalled the time (though less often now) when he was a simple guard concerned only about rules and regulations. From his current perspective, all other posts seemed superficial.

Читать дальше