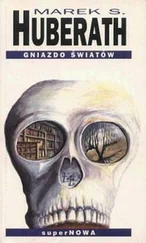

Marek S. Huberath

NEST OF WORLDS

Translated from the Polish by Michael Kandel

All things defined, distinct.

Black and white, zero and one.

Here is song and song alone.

The thuds of the stabilizers stopped; the plane came to rest on the runway. The roar of the engines changed in tone and finally died. But the thunder continued in Gavein’s head; its incessancy now turned into a migraine. Over the loudspeaker, the pilot gave them the time in Davabel.

The trip had taken thirty-six hours—in great discomfort, on a metal seat that locked the hips in a tight cage. Getting up to use the bathroom was possible only during certain announced periods. You could also take off your black metal glasses then. A line would form to the single toilet. Afterward you had to resume your seat and put the glasses on immediately; and again it became insufferably hot. Sweat ran down your back. Your skin itched. Through the glasses the darkness was a brownish purple.

During one of the rest periods, the man next to Gavein had said, “Know why we have to wear these glasses and sit in these ass boxes?”

“No,” Gavein muttered.

The man was seventy, heavy and fat. He overflowed his seat. He pressed against Gavein. “I know, because I’ve flown before. It’s for your protection, double protection…”

He likes to talk, Gavein thought. Retired, obviously. Of course he’s flown before.

“The glasses are so you won’t see how this crate bends and shudders in the wind,” the old man went on. “And the metal seat, that’s so you don’t jump out of the plane in panic in case your glasses fall off.”

Gavein grunted, as though appreciating the joke, but he didn’t start a conversation.

He was deep in his own thoughts. He kept seeing his wife, at the moment of parting. On Ra Mahleiné’s face there had been doubt, apprehension. When an angel loses its faith, it cannot conceal the loss. And her face was an angel’s: mild, sweet, with the innocent, bottomless blue eyes of a child. Gavein had drowned in that blue, and he wished to remain drowned in it for the rest of his life.

At their parting, her eyes were fixed, grave, severe, though bottomless as ever. Not seductive eyes now but hard, unyielding. It was the look of a woman who loves with all her heart and is afraid. Then the tears came. Too soon and too abundantly.

As he walked away down the corridor, her mask cracked.

“Gavein! Gavein!” The cry of a torn heart. Four years of solitude for her, against five of marriage. She struggled as a bird struggles, but two barriers separated them now, and a cordon of officials and soldiers. He could not take her in his arms one more time.

Life had treated them unequally: giving him three days of flight to Davabel, giving her four years on a ship. She chose this herself, to be able to stay with him, to fool time, to get around the marriage law.

They had learned about the law completely by accident. A piece of information, overheard, can change a person’s life. Ra Mahleiné chose the trip of maximum compensation herself; he would never have dreamt of asking her to do such a thing. He was surprised it came to her so easily—she simply told him what they would do.

Painful thoughts—he couldn’t shake them. Fragments of memory passed before him, images.

Their marriage, from the first, had been a breaking of the rules. The most basic rule. Whites were the upper crust in Lavath. Others were treated better in Lavath than in other Lands, but a mixed marriage was out of the question.

Ra Mahleiné was one of those who were given their social category unanimously. Her hair was golden yellow, her eyes azure—not gray, which often indicated a problem.

Gavein began tanning as soon as the spring sun grew strong. Men as a rule had a slightly darker complexion, but with this couple the difference was striking.

A joke: Ra Mahleiné believed that her breasts were too light. She told him this only later, when she was sure of him. Once, before they slept, nestled in his arms, she murmured in her soft, sweet voice that she always thought of them, her breasts, as poor Pale Things, the nipples hardly visible. He never would have believed that such a wonderfully put together white woman could have such a complex.

She told him of her slight physical imperfections before he could notice them himself—and even when he wouldn’t have noticed them. She played with him a little, teasing, obviously able to read his mind, not afraid, only curious for his reaction. Or perhaps she simply prattled like a child, because her thoughts were still innocent, like a child’s, or so he felt.

“You know, I have one shoulder higher than the other,” she once said.

“In Lavath, half the population has a problem with their spines, and anyone who does any sport has uneven shoulders.”

“I have uneven shoulders without a sport.”

“I don’t believe it.”

“You see”—this was at the beginning of their acquaintance—“my spine is crooked, and that’s why the shoulder blades won’t line up. When I’m old, I’ll be a hunchback.”

“It’s possible.”

All she could do then was give him one of those bright looks that fascinated him: defenseless, guiltless, crystal pure. But the mirror of the soul did not reflect everything, for those child’s eyes of hers hid her ability to make decisions and the strength to stick to them.

Lavath law did not forbid marriage between people of different ages. But the precisely tuned system of rewards, discounts, and entitlements kept the difference to a minimum. Couples were supposed to marry upon graduation, not sooner, not later, and of course marry within their social category. The pressure was great, but the two got their way: Ra Mahleiné pretended she was pregnant. That caused a tempest in her family but brought about the desired result. The couple told the truth only after the wedding, when the matter was settled. And then, during the battle with the Office of Segregation, they had all their relatives on their side.

At first they planned the trip in the usual way, without compensation: for both of them, four years of separation. By chance, a worker at the Office of Segregation, a colleague of Ra Mahleiné, told her about the compulsory marriage law.

A change of Land by one spouse automatically annulled the union. Both Ra Mahleiné, staying in Lavath, and Gavein, arriving in Davabel, would have to marry within a period of six months, and in the absence of their own choice they would have to marry persons selected from among arrivals by the local segregation office.

But if they traveled with compensation, they would never have to part again.

Toward the end of the flight, the passengers were finally permitted to remove the metal glasses, though they still had to sit in the frames that gripped their hips. Sometimes the pilot turned on a weak lightbulb to consult his map; the light showed the faces of the passengers. The seats were in pairs, by the windows. The whole interior of the plane: sewn canvas, and the duralumin ribs of the hull, and the frets connecting them, painted dark gray. Here and there the paint was flaking.

“This one is wired together properly,” said Gavein’s neighbor. “Nothing rattles. But I flew once on a metal strato: a national airline, at the altitude of minutes—you understand? On its wings it had only two engines. Awful, as if we were being hammered… The worst was when it fell into an air pocket. Then the wings flapped, like a bird… This one is a different story: solid plates, strong wires. Although the canvas doesn’t keep out the cold…”

Читать дальше