Hiccuping with sobs, he spoke in whispers with Trub. He had made it through the evening’s beating. It was a regular thing, but the victim varied. Every break brought with it the fear that today would be your turn to experience the iron fists of Crooks.

Ordinarily Jaspers would not have reacted. He would even have taken comfort in the fact that he wasn’t the one pounded. But this was an exceptional day, and in addition he felt sorry for the new man.

He stood on spread legs before Crooks and bellowed like a guard: “Older Worker Crooks! Attention! Make your report!”

Crooks started, some water spilling from the pot.

“You… I’ll, I’ll,” he boomed, glaring hatred at his next victim. Not taking his eyes off Jaspers, he put the pot aside. More water spilled.

“Watch who you’re talking to!” Jaspers roared, matching Crooks glare for glare. “Get off that bed now, you stupid sack of meat!”

The silence in the hall was deafening. In the three months since Jaspers arrived, no one had spoken to Crooks in such a tone. Even the guards treated him with a certain deference.

“I… I kill you,” Crooks finally rasped.

“Stand at attention! I am talking to you! From now on you address me as Mister Secretary Sir!” Jaspers continued to roar, aware that Crooks might get a no-food and twelve whacks but not before he beat Jaspers to a pulp. Jaspers waved his sleeve with the three sewn badges that indicated the Secretary function in front of the man’s nose.

“Wha…?” It began to sink in. “Secretary?” The energy drained from Crooks like the air from a punctured balloon. Clumsily he raised and straightened his bear’s body.

“Now you listen, shitface Crooks!” said Jaspers. This was the next command. He wanted to crush his opponent. “Where do you sleep? You sleep on the bottom bunk, by the night lamp… But the night lamp is for reading, for the mental work of the Secretary.”

Crooks didn’t interrupt. Silent, he blinked and looked at Jaspers from under his lashes. Again he was gathering himself.

“You will move to my bunk. You will take your own bedding. Exchange the mattresses too, because I’m not putting my ass in your spilled filthy water… And you had better lie there quietly. I want no straw trickling down on my book. For damaging a possession of the firm, you’ll get a no-food. Is that clear?”

Crooks lowered his head. The Secretary function was important: the Secretary recorded their day’s output, which meant he could write it down as lower, and severe punishment would follow.

“Now do it.”

“Yes, sir, Mister Secretary Sir.”

The hall was silent.

Crooks, out of breath and scrambling, moved his bedding to Jaspers’s bunk and took Jaspers’s bedding down.

“I’ll make the bed myself,” Jaspers told him. No point in tightening the wire more: Crooks might snap.

Jaspers prepared herbal tea, because while Crooks was making his bed, bits of straw fell and got in Jaspers’s nose.

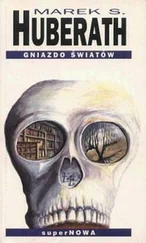

Then Jaspers tightened his sheet per regulations and slipped under the cold blanket. Sipping his tea, he looked at the book in the light of the small lamp. The cover had notches in imitation of a mosaic, and the title was made of little golden flecks: Nest of Worlds: Version 3. The paper was thin, pliable, cream-colored. He opened the book, not at the beginning but after some fifty pages.

* * *

The wind kicked up clouds of fine, gray-white dust. Through them it was hard to see the ribbon of asphalt road, which had not been repaired in years. The shortest route lay through a group of boulders that resembled a dead city or a labyrinth in a hostile waste. The way through the steppe was longer.

This part of Schhian was named Fnorrah, which meant “sounds,” “voices,” “places that played.” The dust of Fnorrah was feared by every living thing. The homes of old residents had been razed to the ground so that no one would stay here long. It even happened sometimes that drivers and passengers passing through died, but these were invariably people whose Significant Name ended either in Int or Myz.

Many travelers heard voices that seemed to come from inside their heads: a babble, an incoherent chorus of whispers, as if several hundred were speaking at once. Yet some people could make out words. They heard exhortations, or recitations, or voices remembered from childhood. At night and during dust storms, the voices of Fnorrah threatened; drivers lost their way, plowed into dunes.

Ozza drove a truck, her eyes watering from staring constantly at the road. Old eyes. Her vision, once sharp and precise, was now good only for distances. Even so, she saw better than Hobeth, who had been myopic her whole life and was now losing her distance vision as well. She dozed now, rocking on her bed in time to the bumps in the asphalt.

Their house truck had been adapted from an old hauler. Instead of a trailer they carried a kiosk converted into a one-room dwelling that included a shower stall and a kitchen recess. A large cylinder containing water had been affixed over the driver’s cabin.

They bought the vehicle together, so they could keep traveling despite their age. Every five years and 219 days a person moved to a different Land, but the governments did not look with favor upon itinerants and tried to limit their number. It was because of the “rootless” that houses stood empty, apartment owners went bankrupt, people didn’t invest in real estate, and buildings became ruins. Construction of new housing complexes had fallen almost to zero. Itinerants were considered poor workers, even when they stayed on the job for some time.

In Schhian, where the two women had arrived this spring, the itinerant lifestyle was barely tolerated. The stout, red-faced border guard inspected the interior of their room and their driver’s cabin.

“Nice babes in these pix!” he shouted to the guard hut, where his colleague was warming himself. “You’ll bring the brochures, Gerd? My heart beats too hard today.”

Ozza attempted to smile, though smiling embarrassed her, and even offered the guard some medicine drops. The other guard emerged reluctantly from the hut. His eyes were cold with contempt. He shoved the legal brochure into their hands and, after the detailed inspection of the vehicle was finished, read them the usual statement.

“In every town you must report immediately to the police,” he finished. On his way back to the hut, after performing this duty, he said to the other, “Blast you for that trick, Appe! Bothering me for two poor old rootless women, one dry as a broom, the other stooped and half blind.”

“The pix, man, the pix,” came the answer from the hut, with a hoarse laugh. Gerd lifted the border barrier for them. Had Ozza been younger, her cheeks would have burned with shame; now they only turned a little pink.

Maybe he had not given them all the leaflets, to be mean. Would the information in their crumpled little notebook be enough? Only a few days and already dog-eared. The brochure with the laws of Schhian had been stuck in a holder on one of the doors in the cabin. Ozza looked in its direction.

If Schhian is setting new restrictions, she thought, that must mean the itinerant life is spreading. More and more people have caught on to our idea.

During the constant traveling that separated a person’s life into equal segments, one kept parting with and meeting the same people, as if the same crew was moving as a group to one ship after another. The new laws indicated that those who preceded them in the constant journey were trying to cope with new conditions.

Читать дальше