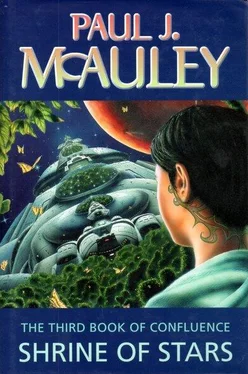

Paul J McAuley

Shrine of Stars

(Confluence-3)

Think on why you were created;

Not to exist like animals indeed,

But to seek virtue and knowledge.

Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy

For my mother

The two ill-matched men were working in a small clearing in the trees that grew along the edge of the shallow reach of water. The larger of the two was chopping steadily at the base of a young blue pine. He wore only ragged trousers belted with a length of frayed rope and was quite hairless, with flabby, pinkish-gray skin and an ugly, vacant face as round as a cheese. The head of his axe had been blackened by fire; its handle was a length of stout pine branch shucked of its bark and held in the socket of the axe head with a ring of carefully whittled wedges. His companion was unhandily trimming branches from a pine bole, using an ivory-handled poniard. He was slender and sleek-headed, like a shipwrecked dandy in scuffed and muddy boots, black trousers and a ragged white shirt with an embroidered collar. A ceramic coin hung from his long supple neck by a doubled leather thong, and a circlet woven from coypu hair and studded with tiny black seed pearls was loose on his upper arm. Now and again he would stop his work and stare anxiously at the blue sky beyond the tree-clad shore.

The two men had already built a raft, which lay near the edge of the water. It was no more than a pentad of blue pine logs lashed together by a few pegged crosspieces and strips of marsh antelope hide, and topped by bundles of reeds. Now they were constructing a pyre, which stood half-completed in the center of the clearing. Each layer of cut and trimmed pine and sweetgum logs was set crosswise to the layer below, and dry reeds and caches of resinous pine cones were stuffed in every chink. The body of a third man lay nearby. It was covered with fresh pine boughs, and had attracted the attention of a great number of black and bronze flies. A fire of small branches and wood chips burned beyond, sending up white, aromatic smoke; strings of meat cut in long strips dangled in the smoke, curling as they dried.

All around was devastation. Swamp cedars, sweetgum trees and blue pines all leaned in the same direction. A few of the biggest trees had fallen and their upturned roots had pulled up wedges of the clayey soil. Nothing remained of the blue pines which had cloaked the ridge above but ash and smoldering stumps. Some way beyond the clearing where the two men worked was a wide, shallow basin of vitrified mud filled with ash-covered steaming water.

Except for the ringing of the axe, the land was silent, as if still shocked by the violence recently done there. On one side, beyond the island’s central ridge and a marshy creek, were the low black cliffs of the old river shore and a narrow plain of dry scrub that ran along the edge of the world; in the other, beyond the reach of shallow, still water, a marsh of yellow reeds stretched toward the edge of the Great River. It was noon, and very hot.

The slender man cut the last branch from the pine bole and straightened and looked up at the sky again. “I don’t see the need to trim logs which are only for burning,” he said. “Do you love work so much, Tibor, that you must always make more?”

“The pyre must go together neatly, little master,” Tibor said, fitting his words to the rhythmic blows of his axe. “It must not fall apart when it burns, and so the logs must be trimmed.”

“We should leave it and go,” the slender man said. “The flier might return at any moment. And call me Pandaras. I’m not anyone’s master.”

“Phalerus deserves a proper funeral. He was a good man. He always bought me cigarette makings wherever the Weazel put into port.”

“Tamora was a good friend,” Pandaras said sharply, “and I buried her burnt bones and the hilt of her sword under a stone. There’s no time for niceties. The flier might come back, and the sooner we start to search for my master, the better.”

“He might be dead too,” Tibor said, and stood back and gave the pine a hard kick above the gash he had cut around its trunk. The little tree leaned and Tibor kicked it again and it fell with a threshing of boughs and a crackling as the last measure of wood in the cut broke free.

“He’s alive,” Pandaras said, and touched the circlet on his arm. “He left the fetish behind so that I would know. He was led into an ambush by Eliphas, but he is alive. I think he entrusted me with his coin and his copy of the Puranas because he suspected that Eliphas might betray him, as Tamora so often said that he would. I swore when I found the fetish and I swear now that I will find him, even if I must follow him to the end of the river.”

Tibor took papers cut from corn husks and a few strands of coarse tobacco from a plastic pouch tucked into the waist of his trousers, and began to roll a cigarette. He said, “We should not have climbed down to the shrine, little master. I know about shrines, and that one had been warped to evil ends.”

“Eliphas lured my master there, if that’s what you mean. If we had not followed them, we would not have learned what happened. Fortunately, I was able to read the clues as any other man might read a story in a book. There was a fight in the shrine, and someone was hurt and ran away. Perhaps Eliphas tried to surprise Tamora from behind, and she managed to defend herself. She wounded him and chased him outside, and that was when she was killed, most likely by someone from the flier. Eliphas didn’t have an energy pistol, or he would have used it much earlier—there would have been no need to lead my master away from the ship into an ambush. But it was an energy pistol that killed poor Tamora, and melted the keelrock of the stair, and no doubt the same energy pistol was used to subdue Yama.”

While Pandaras talked, Tibor crossed to the fire and lit his cigarette with the burning end of a branch. He dropped the branch back into the fire and drew on his cigarette and exhaled a plume of smoke. “We will find the Weazel ,” he said, “and the Captain will help us find your master.”

“They are all dead, Tibor. You have to understand that.”

“We found no bodies except poor Phalerus’s,” Tibor said stubbornly. “And nothing at all of the ship, except the axe head.”

“A fire fierce enough to transmute mud to something like glass would have vaporized the ship like a grain of rice in a furnace. Phalerus was hunting in the marsh near the island, and he was caught in steam flash-heated by the blast of the flier’s light cannon. The others died at once and their bodies were burned up with the ship.”

Pandaras and Tibor had found Phalerus’s scalded body lying near an antelope he had shot. It was clear that the old sailor had not died immediately; he had put the shaft of an arbalest bolt between his teeth and nearly bitten it through in his agony. Pandaras remembered a story that one of his uncles had told him about an accident in a foundry. A man had slipped and fallen waist-deep in a vat of molten iron. The man’s workmates had been paralyzed by his terrible screams, but his father had grabbed a long-handled ladle and had pushed his son’s head beneath the glowing surface. Phalerus had died almost as badly, and he had died alone, with no one to ease his passing.

Tibor started to trim the larger branches from the pine he had felled. After a little while, he stopped and said, “The Captain is clever. She’s escaped pirates before, and that’s what happened here. The flier’s light cannon missed the Weazel , and she made a run for it. Maybe Phalerus was left behind, but the rest will be with the ship. The Captain won’t know your master has been taken, and maybe she’ll come back for him.” He ran a hand over the parallel scars that seamed his broad chest. He said, “I belong with the ship, little master.”

Читать дальше