He felt — and saw, too — how, from out the swathes of vapour, the long soft elephant's trunk of the god Ganesha loosened itself from the head, sunken on the chest, and gently, with unerring finger, felt for his, Freder's forehead. He felt the touch of this sucker, almost cool, not in the least painful, but horrible. Just in the centre, over the bridge of the nose, the ghostly trunk sucked itself fast; it was hardly a pain, yet it bored a fine, dead-sure gimlet, towards the centre of the brain. As though fastened to the clock of an infernal machine the heart began to thump. Pater-noster… Pater-noster… Pater-noster…

"I will not," said Freder, throwing back his head to break the cursed contact: "I will not… I will… I will not… "

He groped for he felt the sweat dropping from his temples like drops of blood in all pockets of the strange uniform which he wore. He felt a rag in one of them and drew it out. He mopped his forehead and, in doing so, felt the sharp edge of a stiff piece of paper, of which he had taken hold together with the cloth.

He pocketed the cloth and examined the paper.

It was no larger than a man's hand, bearing neither print nor script, being covered over and over with the tracing of a strange symbol and an apparently half-destroyed plan.

Freder tried hard to make something of it but he did not succeed. Of all the signs marked on the plan he did not know one. Ways seemed to be indicated, seeming to be false ways, but they all led to one destination; to a place which was filled with crosses.

A symbol of life? Sense in nonsense?

As Joh Fredersen's son, Freder was accustomed swiftly and correctly to grasp anything called a plan. He pocketed the plan though it remained before his eyes.

The sucker of the elephant's trunk of the god Ganesha glided down to the occupied unsubdued brain which reflected, analysed and sought. The head, not tamed, sank back into the chest. Obediently, eagerly, worked the little machine which drove the Pater-noster of the New Tower of Babel.

A little glimmering light played upon the more delicate joints almost on the top of the machine, like a small malicious eye.

The machine had plenty of time. Many hours would pass before the Master of Metropolis, before Joh Fredersen would tear the food which his machines were chewing up from the teeth of his mighty machines.

Quite softly, almost smilingly, the gleaming eye, the malicious eye, of the delicate machine looked down upon Joh Fredersen's son, who was standing before it…

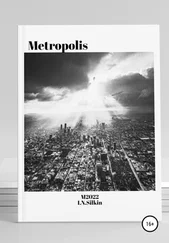

Georgi had left the New Tower of Babel unchallenged, through various doors and the city received him, the great Metropolis which swayed in the dance of light and which was a dancer.

He stood in the street, drinking in the drunken air. He felt white silk on his body. On his feet he felt shoes which were soft and supple. He breathed deeply and the fullness of his own breath filled him with the most high intoxicating intoxication.

He saw a city which he had never seen. He saw it as a man he had never been. He did not walk in a stream of others: a stream twelve flies deep… He wore no blue linen, no hard shoes, no cap. He was not going to work. Work was put away, another man was doing his work for him.

A man had come to him and had said: "We shall now exchange lives, Georgi; you take mine and I yours… "

"When you reach the street, take a car."

"You will find more than enough money in my pockets… "

"You will find more than enough money in my pockets… "

"You will find more than enough money in my pockets… "

Georgi looked at the city which he had never seen…

Ah! The intoxication of the lights. Ecstasy of Brightness! — Ah! Thousand-limbed city, built up of blocks of light. Towers of brilliance! Steep mountains of splendour! From the velvety sky above you showers golden rain, inexhaustibly, as into the open lap of the Danae.

Ah — Metropolis! Metropolis!

A drunken man, he took his first steps, saw a flame which hissed up into the heavens. A rocket wrote in drops of light on the velvety sky the word: Yoshiwara…

George ran across the street, reached the steps, and, taking three steps at a time, reached the roadway. Soft, flexible, a black willing beast, a car approached, stopped at his feet.

Georgi sprang into the car, fell back upon the cushions, the engine of the powerful automobile vibrating soundlessly. A recollection stiffened the man's body.

Was there not, somewhere in the world — and not so very far away, under the sole of the New Tower of Babel, a room which was run through by incessant trembling? Did not a delicate little machine stand in the middle of this room, shining with oil and having strong, gleaming limbs? Under the crouching body and the head, which was sunken on the chest, crooked legs rested, gnome — Like upon the platform. The trunk and legs were motionless. But the short arms pushed and pushed and pushed, alternately forwards, backwards, and forwards. The floor which was of stone and seamless, trembled under the pushing of the little machine which was smaller than a five-year-old child.

The voice of the driver asked: "Where to, sir?"

Straight on, motioned Georgi with his hand. Anywhere…

The man had said to him: Change the car after the third street.

But the rhythm of the motor-car embraced him too delightfully. Third street… sixth street… It was still very far to the ninetieth block.

He was filled with the wonder of being thus couched, the bewilderment of the lights, the shudder of entrancement at the motion.

The further that, with the soundless gliding of the wheels, he drew away from the New Tower of Babel, the further did he seem to draw away from the consciousnes of his own self.

Who was he—? Had he not just stood in a greasy patched, blue linen uniform, in a seething hell, his brain mangled by eternal watchfulness, with bones, the marrow of which was being sucked out by eternally making the same turn of the lever to eternally the same rhythm, with face scorched by unbearable heat, and in the skin of which the salty sweat tore its devouring furrows?

Did he not live in a town which lay deeper under the earth than the underground stations of Metropolis, with their thousand shafts — In a town the houses of which storied just as high above squares and streets as, above in the night, did the houses of Metropolis, which towered so high, one above the other?

Had he ever known anything else than the horrible sobriety of these houses, in which there lived not men, but numbers, recognisable only by the enormous placards by the house-doors?

Had his life ever had any purpose other than to go out from these doors, framed with numbers, out to work, when the sirens of Metropolis howled for him — and ten hours later, crushed and tired to death, to stumble into the house by the door of which his number stood?

Was he, himself, anything but a number — number 11811—crammed into his linen, his clothes, his cap? Had not the number also become imprinted into his soul, into his brain, into his blood, that he must even stop and think of his own name?

And now—?

And now—?

His body refreshed by pure cold water which had washed the sweat of labour from him, felt, with wonderful sweetness, the yielding relaxation of all his muscles. With a quiver which rendered all his muscles weak he felt the caressing touch of white silk on the bare skin of his body, and, while giving himself up to the gentle, even rhythm of the motion, the consciousness of the first and complete deliverance from all that which had put so agonising a pressure on his existence overcame him with so overpowering a force that he burst out into the laughter of a madman, his tears falling uncontrollably.

Violently, aye, with a glorious violence, the great city whirled towards him, like a sea which roars around mountains.

Читать дальше