"Where are you?"

"Here—!"

"But I can't see you—!"

"You must look higher!"

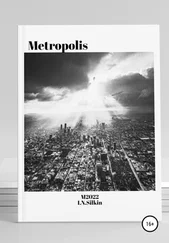

Freder's gaze flitted through the room. He saw his father standing on a platform, between the out-stretched arms of the crosses of Golgotha from the ends of which long, white, crackling sprigs of sparks blazed. In the hellish fires his father's face was as a mask of unmistakable coldness. His eyes were blue-gleaming steel. Amidst the great, raving machine-gods, he was a greater god, and lord of all.

Freder ran over to him, but he could not get up to him. He clung to the foot of the flaming cross. Wild impacts crashed through the New Tower of Babel.

"Father—!" shrieked Freder. "Your city is going to ruin—!"

Joh Fredersen did not answer. The sweeping sprigs of flame seemed to be breaking from his temples.

"Father—! Don't you understand—? Your city is going to ruin! — Your machines have come to life! — They are dashing the town to pieces — They are tearing Metropolis to tatters! — Do you hear—? Explosion after explosion—! I have seen a street in which the houses were dancing upon their shattered foundations — just like Little children dancing upon the stomach of a laughing giant… A lava-stream of glowing copper poured itself out from the split-open tower of your boiler-factory, and a naked man was running before it, a man whose hair was charred and who was roaring: 'The end of the world has come—!' But then he stumbled and the copper stream overtook him… Where the Jethro works stood, there is a hole in the earth which is filling up with water. Iron bridges are hanging in shreds between towers which have lost their entrails, cranes are dangling on gallows like men hanged. And the people, incapable of flight as of resistance, are wandering about among houses and streets, both of which seemed doomed… "

He clasped his hands about the stem of the cross and threw his head back into his neck, to see his father quite clearly, quite openly in the face.

"I cannot believe, father, that there is anything mightier than you! I have cursed your overwhelming might — your overwhelming might which has filled me with horror, from the bottom of my heart. Now I run to you and ask you on my knees: Why do you allow Death to lay hands on the city which is your's—?"

"Because Death has come upon the city by my will."

"By your will—?"

"Yes."

"The city is to perish—?"

"Don't you know why, Freder?"

There was no answer.

"The city is to go to ruin that you may build it up again… "

"— I—?"

"You."

"Then you are laying the murder of the city on my shoulders?"

"The murder of the city reposes on the shoulders of those alone who trampled Grot, the guard of the heart-machine, to death."

"Did that also take place by your will, father?"

"Yes!"

"Then you forced them to commit the crime—?"

"For your sake, Freder; that you could redeem them… "

"And what about those, father, who must die with your dying city, before I can redeem them!"

"Concern yourself about the living, Freder — not about the dead."

"And if the living come to kill you—?"

"That will not happen, Freder. That will not happen. The way to me, among the raving god-machines, as you called them, could only be found by one. And he found it. That was my son."

Freder dropped his head into his hands. He rocked it to and from as if in pain. He moaned softly. He was about to speak; but before he could speak a sound ripped the air, which sounded as though the earth were bursting to pieces. For a moment, everything in the white room seemed to hover in space, a foot above the ground — even Moloch and Baal and Huitzilopochtli and Durgha, even the hammer of Asa Thor and the Towers of Silence. The crosses of Golgotha, from the ends of the beams of which long, white crackling sprigs of sparks were blazing, fell together and then straightened up again. Then everything crashed back into its place with furious emphasis. Then all the lights went out. And from the depths and distance the city howled.

"Father—!" shouted Freder.

"Yes. — Here I am. — What do you want?"

"… I want you to put an end to this nightmare—!"

"Now? — now—!"

"But I don't want any more people to suffer—! You must help them — you must save them, father—!"

"You must save them. Now — Immediately!"

"Now? no!"

"Then," said Freder, pushing his fists out far before him, as if pushing something away from him, "then I must seek out the man who can help me — even if he is your enemy and mine."

"Do you mean Rotwang?"

No answer. Joh Fredersen continued:

"Rotwang cannot help you."

"Why not—"

"He is dead."

Silence. Then, tentatively, a strangled voice which asked:

"Dead…

"Yes."

"How did he come… so suddenly… to die?"

"He died, chiefly, Freder, because he dared to stretch out his hands toward the girl whom you love."

Trembling fingers fumbled up the stem of the cross.

"Maria, father — Maria…?"

"So he called her."

"Maria — was with him? — In his house—?"

"Yes, Freder."

"Ah—! see. — ! see—!.. And now—!"

"I do not know."

Silence.

"Freder?"

No answer came.

"Freder—?"

But a shadow ran past the windows of the white machine-cathedral. It ran, ducked down, hands thrown behind its neck, as if it feared that Durgha's arms could snatch at it, or that Asa Thor could hurl his hammer, which never failed, at it from behind, in order, at Joh Fredersen's command, to prevent its flight.

It did not penetrate into the consciousness of the fugitive that all the machines were standing still because the heart, the unguarded heart of Metropolis, under the fiery lash of the "12," had raced itself to Death.

MARIA FELT SOMETHING licking at her feet, like the tongue of a great, gentle dog. She bent down to fumble for the animal's head, and felt that it was water into which she was groping.

From where did the water come? It came silently. It did not splash. Neither did it throw up waves. It just rose-unhurriedly, yet persistently. It was not colder than the air round about. It lapped about Maria's ankles.

She snatched her feet back. She sat, crouched down, trembling, listening for the water which could not be heard. From where did it come?

It was said that a river wound its way deep under the city. Joh Fredersen had walled up its course when he built the subterranean city, the wonder of the world, for the workmen of Metropolis. It was also said that the stream fed a mighty water-basin and that there were pump-works there, which were powerful enough, inside of less than ten hours either completely to empty or to fill the water basin — in which there was room for a medium-sized city. One thing was certain — that, in the subterranean, workmen's city, the throbbing of these pumps was constantly to be heard, as a soft, incessant pulse-beat, if one laid one's head against a wall — and that, if this pulse-beat should ever become silent, no other interpretation would be conceivable than that the pumps had stopped, and that then the river was rising.

But they had never — never stopped.

And now—? From where was the silent water coming? — Was it still rising—?

She bent forward. She did not have to stretch her hand down very low to touch the cool brow of the water.

Now she felt, too, that it was flowing. It was making its way with great certainty of aim in one direction. It was making its way towards the subterranean city-Old books tell of saintly women, whose smile at the moment of preparing themselves to gain the martyr's crown, was of such sweetness that the torturers fell at their feet and hardened heathens praised the name of God.

Читать дальше