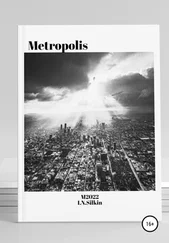

Those who stared at him when he arrived at the New Tower of Babel seemed to be seeing, not him, but a spirit…

He was about to enter the Pater-noster, which was pumping its way, a scoop-wheel for human beings, through the New Tower of Babel. But a sudden shudder pushed him away from it. Did there not crouch below, deep, deep, down, under the sole of the New Tower of Babel, a little, gleaming machine, which was like Ganesha, the god with the elephant's head? Under the crouching body, and the head, which was sunken on the chest, crooked legs rested, gnome — Like, upon the platform. The trunk and legs were motionless. But the short arms-pushed and pushed and pushed, alternately, forwards, backwards, forwards.

Who was standing before the machine now, cursing the Lord's Prayer — the Lord's Prayer of the Pater-noster machine?

Shivering with horror, he ran up the stairs.

Stairs and stairs and stairs… They would never come to an end… The brow of the New Tower of Babel lifted itself very near to the sky. The tower roared like the sea. It howled as deep as the storm. The hurtling of a water-fall boomed in its veins.

"Where is my father?" Freder asked the servants.

They indicated a door. They wanted to announce him. He shook his head. He wondered: Why were these people looking so strangely at him?

He opened a door. The room was empty. On the other side, a second door, ajar. Voices behind it. The voice of his father and that of another…

Freder suddenly stood still. His feet seemed to be nailed to the floor. The upper part of his body was bent stiffly forwards. His fists dangled on helpless arms, seeming no longer capable of freeing themselves from their own clench. He listened; the eyes in his white face were filled with blood, the lips were open as though forming a cry.

Then he tore his deadened feet from the floor, stumbled to the door and pushed it open…

In the middle of the room, which was filled with a cutting brightness, stood Joh Fredersen, holding a woman in his arms. And the woman was Maria. She was not struggling. Leaning far back in the man's arms, she was offering him her mouth, he alluring mouth, that deadly laugh…

"You…!" shouted Freder.

He dashed to the girl. He did not see his father. He saw only the girl — no, neither did he see the girl, only her mouth and her sweet, wicked laugh.

Joh Fredersen turned around, broad and menacing. He let the girl go. He covered her with the might of his shoulders, with the great cranium, flamed with blood, and in which the strong teeth and the invincible eyes were very visible.

But Freder did not see his father. He only saw an obstacle between him and the girl.

He rushed at the obstacle. It pushed him back. Scarlet hatred for the obstacle choked him. His eyes flew around. They sought an implement — an implement which could be used as a battering ram. He found none. Then he threw himself toward as a battering ram. His fingers clutched into stuff. He bit into the stuff. He heard his own breath like a whistle, very high and shrill. Yet within him there was only one sound, only one cry: "Maria—!" Groaningly, beseechingly: "Maria—!!"

A man dreaming of hell shrieks out no more, in his torment, than did he.

And still, between him and the girl, the man, the lump of rock, the living wall…

He threw his hands forward. Ah… look!..there was a throat! He seized the throat. His fingers snapped fast like iron fangs.

"Why don't you defend yourself?" he yelled, staring at the man.

"I'll kill you—! I'll take your life—! I'll murder you—!"

But the man before him held his ground while he throttled him. Thrown this way and that by Freder's fury, the body bent, now to the right, now to the left. And as often as this happened Freder saw, as through a transparent mist, the smiling countenance of Maria, who, leaning against the table, was looking on with her sea water eyes at the fight between father and son.

His father's voice said: "Freder… "

He looked the man in the face. He saw his father. He saw the hands which were clawing around his father's throat They were his, were the hands of his son.

His hands fell loose, as though cut off… he stared at his hands, stammering something which sounded half like an oath, half like the weeping of a child that believes itself to be alone in the world.

The voice of his father said: "Freder… "

He fell on his knees. He stretched out his arms. His head fell forward into his father's hands. He burst into tears, into despairing sobs…

A door slid to.

He flung his head around. He sprang to his feet. His eyes swept the room.

"Where is she?" he asked.

"Who?"

"She-… "

"Who—?"

"She… who was here… "

"Nobody was here, Freder… "

The boy's eyes glazed.

"What did you say—?" he stammered.

"There has not been a soul here, Freder, but you and I."

Freder twisted his head around stiffly. He tugged the shirt from his throat. He looked into his father's eyes as though looking into well-shafts.

"You say there was not a soul here… I did not see you… when you were holding Maria in your arms… I have been dreaming… I am mad, aren't I?… "

"I give you my word," said Joh Fredersen, "when you came to me there was neither a woman nor any other living soul here… "

Freder remained silent. His bewildered eyes were still searching along the walls.

"You are ill, Freder," said his father's voice.

Freder smiled. Then he began to laugh. He threw himself into a chair and laughed and laughed. He bent down, resting both elbows upon his knees, burrowing his head between his hands and arms. He rocked himself to and fro, shrieking with laughter.

Joh Fredersen's eyes were upon him.

THE AEROPLANE WHICH had carried Josaphat away from Metropolis swam in the golden air of the setting sun, rushing towards it at a tearing speed, as though fastened to the westward sinking ball by metal cords.

Josaphat sat behind the pilot. From the moment when the aerodrome had sunk below them and the stone mosaic of the great Metropolis had paled away into the inscrutable depths, he had not given the least token that he was a human being with the faculty for breathing and moving. The pilot seemed to be taking a pale grey stone, which had the form of a man, with him as freight and, when he once turned around, he looked full into the wide open eyes of this petrified being without meeting a glance or the least sign of consciousness.

Nevertheless Josaphat had intercepted the movement of the pilot's head with his brain. Not immediately. Not soon. Yet the vision of this cautious, yet certain and vigilant movement remained in his memory until he at last comprehended it.

Then the petrified image seemed to become a human being again, whose breast rose in a long neglected breath, who raised his eyes upwards, looking into the empty greenish blue sky and down again to the earth which formed a flat, round carpet, deep down in infinity — and at the sun which was rolling westwards like a glowing ball.

Last of all, however, at the head of the pilot who sat before him, at the airman's cap which turned, neckless, into shoulders filled with a bull — Like strength and a forceful calm.

The powerful engine of the aeroplane worked in perfect silence. But the air through which the aeroplane tore was filled with a mysterious thunder, as though the dome of heaven were catching up the roaring in the globe and throwing it angrily back again.

The aeroplane hovered homelessly above a strange earth, like a bird not able to find its nest.

Suddenly, amid the thunder of the air, the pilot heard a voice at his left ear saying, almost softly: "Turn back… "

The head in the airman's cap was about to bend backwards. But at the first attempt to do so it came in contact with an object of resistance, which rested exactly on the top of his skull. This object of resistance was small, apparently angular and extraordinarily hard.

Читать дальше