Brezan’s stomach knotted up even more. Next time I get a personal call , Brezan thought, I’m going to take some anti-anxiety medications first .

“I assume you’ve heard,” Miuzan said carefully, “but in case you haven’t, there are reports of difficulties with mothdrives. So far they correlate rather disturbingly with regions of calendrical rot. I can send you the databurst if you want it. Call it the general’s gift to you, for your contemplation. But this is all to say that we need to stabilize the hexarchate sooner rather than later, before all our defenses and intersystem trade shut down.”

How had he missed this? Unless it had been buried in the piles of reports and dispatches that he struggled to make it through every day. Considering he hadn’t been doing the job for long, he was already impressively behind.

“Let me guess,” Brezan said. While he was no engineer, he knew about the fundamentals of mothdrive technology. “The harnesses aren’t working properly anymore.”

Obvious once she brought it up, really. Voidmoths were biological in origin, hatched at mothyards and then fitted with technological implants to make them suitable conveyances or weapons of war. Calendrical rot had always threatened the efficacy of the harnesses that controlled the mothdrives. Voidmoths were additionally fitted with invariant maneuver drives for a reason.

Miuzan’s mouth twisted. “Surprised you didn’t see this coming, little brother.”

“It’s been a busy few weeks,” Brezan said. He swallowed his pride and added, “You’re right, though. It’s inexcusable to lose sight of a detail this important.”

“Well,” Miuzan said, “that’s settled.”

Wait, how had she—“Excuse me,” Brezan said, tamping down on a flare of anger. “I haven’t agreed to anything. Tell General Inesser I appreciate her warning.” He did, sincerely. “But I can’t support her.”

For once Miuzan was at a loss for words. Her nostrils flared, and she slitted her eyes at him for several long moments.

“It’s simple,” Brezan said despite the stabbing in his heart. “If the general is bothering with me at all, it’s because she thinks I’m a threat. Maybe not much of a threat, but that means I have a chance. And I have to do this—not for myself, but for all the people who can be saved from the Vidona.”

“You—” Miuzan breathed in, expelled it in an angry huff. “You’re putting your ego and a bunch of heretics before the safety of a lot of innocent people.”

“Once upon a time, some of those heretics were ‘innocent people’ themselves,” Brezan shot back. “How many times have we seen it, Miuzan? Some group of people who’d been going about their lives for decades, longer even, and then overnight they’re the new heretics because the Vidona have come up with some new fiddly regulation just for the purpose of scaring up new victims? I don’t want to be a part of that anymore.”

“All right.” Miuzan’s voice had gone dead soft, never a good sign. “I wasn’t going to say this to you, but you’re not leaving me much choice.”

There’s always a choice , Brezan thought. Still, he might as well let her have her say. She wouldn’t leave him alone until she got everything out.

“You are setting the lives of a handful of people over those of everyone in the whole hexarchate . So maybe the old government had spots of corruption. That doesn’t mean the solution is to burn everything down.”

“That’s already done and over with,” Brezan said, because he couldn’t help himself.

Miuzan continued speaking over him so that he had to strain to hear her. Which was the intended effect, no doubt. “The hexarchate’s worlds are already bleeding because of you. By the time you’re done with this, this—” She searched for a word; found one. “—temper tantrum of yours, they’re going to be drenched. I hope that makes you happy.”

Brezan’s temper, always precarious, got the better of him. “Thank you for thinking so well of me,” he said in a cold, flat voice. “Because I don’t see that what your precious general is trying to do is so different, except she doesn’t care about anything but restoring the old order. Tell me, when the two of you stopped to observe the Day of Shallow Knives recently and watched the cuts being made, and all the blood, did you even wonder about the name of the poor fucker who was tortured to death for you?”

“It was a heretic ,” Miuzan snapped back. “I see this entire call has been a waste of time. I shouldn’t have suggested it to the general in the first place. I would never have guessed that you’d pick some crazed personal ambition over honor and loyalty and family, but it seems you’re capable of surprising me after all.”

“Fuck off,” Brezan said.

Miuzan’s face shuttered. Then she severed the connection.

It was the last communication Brezan was to have with anyone in his family for the next nine years.

CHAPTER SIX

SAYING FAREWELL TO Rhombus and Sieve only took Hemiola a few minutes. “Keep out of trouble,” Rhombus said, as if Hemiola hadn’t yet experienced its first neural flowering. That was all.

Sieve, on the other hand, presented Hemiola with a touching and entirely impractical sculpture of bent wires and other scraps. “In case the real hexarch wants some extra decorations once you find him,” it said.

“If we catch up to him, I’ll put it where he can see it,” Hemiola said tactfully.

Hemiola had already presented Jedao with the archive, copied to a data solid the size of his hand. It approved of how carefully Jedao handled it. Just because it was a copy didn’t mean it wasn’t valuable.

It accompanied Jedao outside of Tefos Base with trepidation. The staircase had scarcely changed in all that time. Jedao had added his footsteps to the multiple sets in the layer of dust upon the stairs. Tefos had little in the way of atmosphere. Down here, sheltered from the slow patter of micrometeorites, the footsteps would endure for a long time. Some of them dated back to when the hexarch had first brought the three servitors with him.

When they emerged from the crevasse, two of the system’s other moons rode high in a sky sprinkled with stars and the glow-swirl of the local nebulae. Tefos’s surface, ordinarily a dull bluish gray, was desaturated further in the low light. Jedao switched on his headlamp. Hemiola brightened its lights as well, in case he needed the extra help seeing his way.

They passed the rock garden on the way. After eighty years, the carefully raked sand had eroded just a little. Guiltily, Hemiola found it liked the effect. But Sieve would want to fix it up so it looked just as it had eighty years ago. By the time Hemiola returned, the garden would no doubt be restored to its original state.

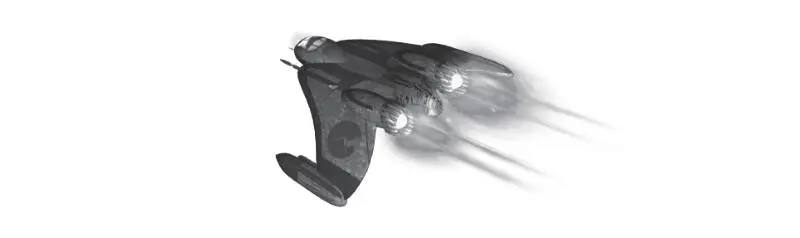

Jedao’s voidmoth rested on a ridge a short walk from the garden. Its elongated shadow stretched away from them, disappearing off the back of the ridge. The moth itself formed a narrow triangular wedge with its apex tilted slightly skyward, as though it yearned to fly again. While the moth was an unpitted matte black, its landing gear gleamed with a sheen as of mirrors. Promisingly, the moth’s power core was properly shielded. Like many servitors, even servitors not of particularly technical bent, Hemiola had strong feelings about shielding. Maybe this meant that Jedao took good care of his transportation.

Except—

“There’s someone on your moth,” Hemiola said, stopping as the moth unfurled a ramp. Its scan had picked up another servitor, although it wasn’t yet visible to human eyes.

Читать дальше