For Alice Jackson—

We had some fun when the Mississippi

Gulf Coast was a reporter’s dream.

Acknowledgments

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

I can never write about newspapers and journalists without thanking my parents, who drew me into the profession they loved. When I was so small I had to stand on a wooden box, I disassembled the slugs of hot type to be melted and reset for the next edition of the paper.

My parents, Roy and Hilda Haines, burned with the passion of true journalists, and they passed that love to me.

In my life I’ve been privileged to know many fine reporters and editors. The Sellers family in Lucedale gave me my first paid job at a weekly at the age of seventeen. Leonard Lowry, Fitz McCoy, Elliot Chase, Sarah Gillespie, Robert Miller, Fallon Trotter, John Fay, Buddy Smith, Rhee Odom, Tom Roper, Gary Smith, Ann Hebert, Jim Young, Doug Sease, Bill Minor, Elaine Povich, Ronni Patriquin Clark, Jim Tuten, Lee Roop, B. J. Richey, Phil Smith—each one of them helped me down the road toward becoming a better reporter and also helped me recognize my limitations.

Newspapering gave me opportunities that few young people ever see. I owe the people I worked with many thanks.

As always, I owe thanks to my critique group, the Deep South Writers Salon: Renee Paul, Alice Jackson, Susan Tanner, Stephanie Chisholm, Gary and Shannon Walker and Aleta Boudreaux.

My agent, Marian Young, is the best. And the editorial staff at MIRA can’t be beat. Thank you, Lara Hyde, Valerie Gray and Sasha Bogin.

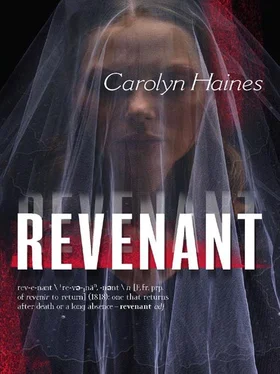

I’m knocked over by the terrific cover and the hard work that Erin Craig put into creating a design that conveyed so much of the story. This book has been a terrific experience from beginning to end.

Thank you all.

A seagull swooped low over the white, man-made beach of Biloxi. The midmorning sun was bright, and I squinted against the glare of the sparkling Mississippi Sound. The water held potential. An accidental drowning wouldn’t be a bad way to go, and it would be so much easier on my parents than suicide. My BlackBerry buzzed against my waist, disrupting the constant whisper of the water, the promises of numbness and sleep. I turned back to my truck and checked the number. The newspaper. I was late again.

A discarded coin cup clattered across the parking lot. Casinos, the new Mississippi cash crop. The Gulf Coast was second only to Las Vegas for gaming, a point of pride for those who saw growth as the only indication of progress. The garish casinos, complete with parking garages and hotels, were a blight, built by people who’d forgotten a storm called Camille and the damage of two-hundred-mile-per-hour winds. Talk about a gamble—putting huge floating barges in the Mississippi Sound. It was 2005, and thirty-six years had passed since Hurricane Camille wiped out the Gulf Coast. But Mother Nature, like a guilty conscience, only feigns sleep.

Of course, mine was the minority opinion in a town that had finally seen the promise of two cars in every garage fulfilled by the economic boost brought by the lure of the one-armed bandits.

It was only March, but already the hurricane experts were predicting a bad year for 2005. In a different place and time, I might have wanted to see the list of construction materials used on the hotels and new condominiums that crowded the coastline. If the construction was not up to standards, a Category Five hurricane, like Camille, could be death and destruction. In the past, that would have caught my professional interest, but not anymore. I was done with all of that.

I drove to the newsroom of the Morning Sun, ignoring the hostile glances of my coworkers as I went into my office and closed the door. They’d converted a conference room to make my office and indentations from the heavy table were still in the carpet. My desk and computer were at the end of the room beside the long narrow window that reminded me of a fortress. If the Injuns, or the liberals, surrounded us, I’d have a place for my shotgun. The paper’s policy would be to shoot on sight.

My telephone rang. “Where the hell have you been? It’s almost ten o’clock. We’re running a daily newspaper here, Carson, not a magazine.”

In my three weeks of employment, nothing had happened that warranted my presence at the paper at eight. “Sorry, Brandon,” I said. “I was busy contemplating suicide, but I’m too much of a coward to carry through with it. So, what’s going on?” I fumbled through a desk drawer for an aspirin bottle. Perhaps I should have apologized to Brandon Prescott, the publisher, but I didn’t care for him or my job.

“Drop the pity party, Carson. We don’t have time for it. They’re bulldozing the Gold Rush. When they started scraping up the parking lot they found a grave with five bodies in it. It’s the biggest story of the decade. Joey’s already there. I want you over there right now. And what the hell good is that pager unless you turn it on!”

Brandon was steamed, but there was always something that had his blood pressure at the boiling point. Lately, it was me, his prize. He’d dragged me out of the gutter and put me in a suit and an office with an official press badge. If I were a better person, I’d be grateful.

“I’m on the way,” I said, surprised at the tingle at the base of my skull. My reptilian brain felt a surge. Five bodies buried at one of the most glamorous—and notorious—nightclubs along the Gulf Coast. It could be a big story. In the ’70s and ’80s, the Gold Rush had been the pre-casino gathering place of the Dixie Mafia and the late-night party place where the young and beautiful of all social strata came to be seen. It was even possible someone had pushed up the tarmac and uncovered Jimmy Hoffa. After all, it was the Mississippi Gulf Coast. Anything was not only possible, but it was also probable.

I walked out of my office and was met with the baleful glares of six reporters. They already knew about the bodies, and they’d been hoping it would be their story. By rights, it should have belonged to one of them. But I had the big name and I got the choicest scraps Brandon tossed. I walked out into the March sunshine, hoping the bodies were either very old or very fresh.

Once upon a time, driving along the Mississippi Gulf Coast had been a pleasure. Miles of lazy, four-lane Highway 90 hugged the beaches where there were more migratory birds than fat sunbathers. With the advent of gambling in 1992, all of that changed. Sunbathers were already on the beach, even though the March sun had barely warmed the water above sixty degrees. For at least a mile ahead the traffic was almost at a standstill. If I didn’t get to the Gold Rush soon, the bodies would be bagged and moved. In an effort to calm down, I turned my radio to a country oldies station. There was always a chance I’d catch a Rosanne Cash tune.

Instead, I got Garth Brooks and “The Dance.” There had been a time when I agreed with the sentiment expressed in the song. I’d changed. There were very few experiences worth the pain. I flipped off the radio and took a deep breath. Traffic started moving, and in another fifteen minutes I was at the club.

Читать дальше