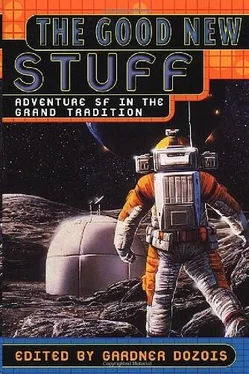

Стивен Бакстер - The Good New Stuff

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Стивен Бакстер - The Good New Stuff» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2002, ISBN: 2002, Издательство: St. Martin's Griffin, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Good New Stuff

- Автор:

- Издательство:St. Martin's Griffin

- Жанр:

- Год:2002

- ISBN:0-312-26456-9

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Good New Stuff: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Good New Stuff»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Good New Stuff — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Good New Stuff», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

So I keep the job. Stomach-thinking. Heth says in the Proverbs that our life hinges on little things. That's certainly true for me.

I eat slowly and carefully; I know that if I eat too much, I'll be sleepy. But I fill my pack with boxfruit, pigeon's egg dumplings, and red peanuts. Especially red peanuts— a person can live a long time on red peanuts. While I'm eating, Shell-sea comes up and sits on the stern to watch me. As I said, I'm not tall, most men have a bit of reach on me, and she's nearly my height. She's wearing a school uniform, the dark red of one of the orders, and her thick hair is tied back with a red cord. The uniform would be fine on a young girl, but only emphasizes that she's not a child. She's too old for bare arms, for uncovered hair, too old for the cord that belts the robe high under her small breasts. She is probably just past menses.

After I eat, I use a bucket to rinse my hands and face. After awhile she says, "Why don't you take off your shirt when you wash?"

"You are a forward child," I say.

She has the grace to blush, but she still looks expectant. She wants to see how much hair I have on my chest. Southerners don't have much body hair.

"I've already bathed today," I say. Southerners waiting to see if I look like a hairy termit make me very uncomfortable. "Why do you have such an unusual name?" I ask.

"It's not a name, it's a nickname." She stares at her bare toes and they curl in embarrassment. I thought she was a bit of a half-wit, but away from Barok she's quick enough, and light on her feet.

I wonder if she's his fancy girl. Most southerners don't take a pretty girl until they already have a first wife.

"Shell-sea? Why do they call you that?"

"Not 'Shell-sea'," she says, exasperated,

"Chalcey. What kind of name is 'Shell-sea'? My name is Chalcedony. I bet you don't know what that is."

"It's a precious stone," I say.

"How did you know?"

"Because I've been to the temple of Heth in Thelahckre," I say, "and the Shesket-lion's eyes are two chunks of chalcedony." I rinse my bowl in the bucket, then dump the water over the side; the soap scums the green water like oil. I'd been to a lot of places, trying to find the right place. The islands hadn't proven to be any better than the city of Lada on the coast. And Lada no better than Gibbun, which was supposed to be full of work, but the work was all for the new star port that the Cousins were building. My people forgetting their kin, living in slums. And Gibbun no better than Thelahckre.

"Why don't you have a beard?" she asks. Southerners can't grow beards until they're old, and then only long, bedraggled, wispy white things. They believe that all northerner men have them down to their belts.

"Because I don't," I say, irritated. "Why do you live with Barok?"

"He's my uncle."

We both stop then to watch a ship come down the river to the bay. Like the one the Cousin came in on, it has red eyes rimmed in violet, and violet sails. " 'Temperance,' " I read from the side.

Chalcey glances at me out of the corner of her eye.

I smile. "Yes, some northerners can even read."

"It's a ship of the Brothers of Succor," she says. "I go to the school of the Sisters of Clarity."

"And who are the Sisters of Clarity?" I ask.

"I thought you knew everything," she says archly. When I don't rise to this, she says, "The Sisters of Clarity are the sister order to the Order of Celestial Harmony."

"I see," I say, watching the ship glide down the river.

Testily, she adds. "Celestial Harmony is the first Navigation Order."

"Do they sail to the mainland?"

"Of course," she says, patronizing.

"What does it cost to be a passenger? Do they ever hire cargo-handlers or bookkeepers or anything like that?" I know the answer, but I can't help myself from asking.

She shrugs, "I don't know, I'm a student." Then, sly again, "I study drawing."

"That's wonderful," I mutter.

Passage out of here is my major concern. No one can work on a ship who isn't a member of a Navigational Order, and no order is likely to take a blond-haired northerner with a sudden vocation. Passage is expensive.

Even food doesn't keep me from being depressed.

The guests begin to arrive just after sunset, while the sky is still indigo in the west. I'm in the hold with two food servers. I'm sweltering in my jacket, they're (both women) serene in their blue robes. I play simple songs. Barok comes by and says to me, "Sing some northern thing."

"I don't sing," I say.

He glares at me, but I'm not about to sing, and he can't replace me now, so that's that. But I feel guilty, so I try to be flashy, playing lots of trills, and some songs that I think might sound strange to their ears.

It's a small party, only seven men. Important men, because five boats clunk against ours. Or rich men. It's hard for me to make decisions about southerners, they act differently and I don't know what it means. For instance, southerners never say "no." So at first, I decided that they were all shifty bastards, but eventually I learned how to tell a "yes" that meant no from a "yes" that meant yes.

It's not so hard— if you ask a shopkeeper if he can get you ground proyakapiti, and he says, "yes," then he can.

If he giggles nervously and then says "yes," he's embarrassed, which means that he doesn't want you to know that he isn't able to get it, so you smile and say that you will be back for it later. He knows you are lying, you know he knows; you are both vastly relieved.

But these men smile and shimmer like oil, and Barok smiles and shimmers like oil, and I don't know what's cast, only that if tension were food, I could cut thick slices out of the air and dine on it.

There are no women except servers. I don't know if there are ever women at southern parties, because this is my first one. If a southern man toasts another, he cannot decline the toast without looking like a gelded stabos, so they drink a great deal of wine. After awhile, it seems to me that a man in green, ferret-thin, and a man in yellow are working together to get Barok drunk. If one of them toasts Barok, a bit later the other one does too. Barok would be drinking twice as much as they are, except that Barok himself toasts his guests, especially the ferret, a number of times, so it's hard to say. Besides, Barok is portly and can drink a great deal of wine.

But the servers are finished and cleaning up on deck, and Barok is near purple himself when he finally raps on the table for silence. I stop playing, and tap the bare sword under the serving table behind me with my foot, just to know where it is.

Barok clears a space on the long thin banquet table and claps his hands. Chalcey comes in, dressed in a robe the color of her school uniform, but with her arms and hair decently covered. The effect is nice, or would be if she didn't have that sullen, half-wit face she wears around her uncle.

She puts two rolled papers on the table, and then draws her veil close around her chin and crouches down like a proper girl. Barok opens one of the rolls, and I crane my head before the men close around it. All I get is a glimpse of one of Chalcey's squiggly-line drawings, with some writing on it. The men murmur. The man in yellow says, "What is this?"

"Galgor coast," Barok points, "Lesian and Cauldor Islands, the Liliana Strait."

Charts? Navigation charts of the Islands? How could Barok have gotten… or rather, how could Chalcey have drawn… She is studying drawing with an Order, though, isn't she?

Chalcey drew the charts? But the Cousins have sold magic to the Navigational Orders to make sure students can't take out so much as a piece of paper. How does she get them out of the school?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Good New Stuff»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Good New Stuff» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Good New Stuff» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.