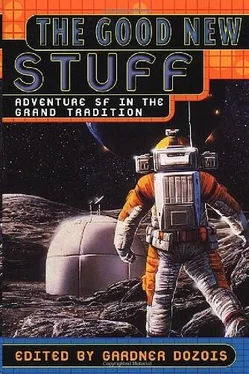

Стивен Бакстер - The Good New Stuff

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Стивен Бакстер - The Good New Stuff» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2002, ISBN: 2002, Издательство: St. Martin's Griffin, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Good New Stuff

- Автор:

- Издательство:St. Martin's Griffin

- Жанр:

- Год:2002

- ISBN:0-312-26456-9

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Good New Stuff: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Good New Stuff»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Good New Stuff — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Good New Stuff», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

She is tall, taller than me, but Cousins are usually tall, and I'm shorter than many men. She looks up directly at me while I am smiling, by chance. The length of a man between us. I can see that she has light eyes.

"Hello," I say in the trade language of the Cousins. The word just pops out.

It stops her, though, like a roped stabros calf. "Hello," she says, in the same tongue. Consternation among the guildmen; two in dark red and one in green, all with shaven heads dull with the graphite sheen of stubble. "You speak lingua?" she says.

"A little," I say.

Then she rattles on, asking me something, "where da-da da-da da."

I shrug. Search my memory. My lessons in lingua were a lifetime ago; I remember almost nothing. Something comes to me that I often said in class: "I don't understand," I say, "I speak little."

"Where did you learn?" she says in Suhkhra, the language of the southerners. "Starport?"

"Up north." No real answer. Already I'm sorry I spoke. Bad enough to be a tokking foreigner; worse to be a spectacle. And my head aches, and I am tired from three days' lack of food.

"Did you work at the port?" she asks, probing.

"No," I say. Flat.

She frowns. Then, like a boat before bad winds, she comes across in another direction. She speaks in my own language, the language of home. "What is your name?" She is careful and stilted in that one phrase.

"Jahn," I say, probably the commonest name among northern men. "What is yours?" I ask, without regard for courtesy.

"Sulia," she says. "Jahn, what kin-kind?"

"My kin are all dead," I say, "Jahn no-kin-kind."

But she shakes her head. "I'm sorry," she says in Suhkhra, "I don't understand. I speak very little Krerjian. What did you say your name was?"

"Jahn Sckarline," I say. And then, in my own tongue, "Go away." Because I am tired of her, tired of everything, tired of starving.

She isn't listening, and probably doesn't understand anyway. "Sckarline," she says. "I thought everyone from Sckarline—"

"Is dead," I say. "Thank you, Cousin. I am pleased you keep my kin-name." It's awkward to say in Suhkra. The Suhkra aren't good at irony anyway.

"Sulia Cousin," one of the guildmen says deferentially, "they are waiting for us."

She shakes him off. "I know about the settlement at Sckarline," she says to me. "You're a mission boy. You have an education. Why don't you work at a port?"

"And live in a ghetto?"

The word comes back to me in her trade lingua. "With the other natives?"

"Isn't it better to get a tech job than to live like this?" she asks.

Better than a shantytown, I think, huddled together while the starships come screaming overhead, making one's teeth ache and one's goods rattle?

I look at her, she looks at me. I search my memory for the words in lingua, but my mind isn't sharp and it was too long ago. "Go away," I finally say in Suhkhra, "people are waiting."

She stands there hesitant, but the guildman does not. He strides forward and smacks me hard in the side of my head for my disrespect. I know better than to defend myself. Oh, Heth, my poor head! Southerners are a bad lot, they have no concept of a freeman.

So, having been knocked over, I stay still, with my nose near the stones, waiting to see if he'll hit me again, smelling dust, and sea, and the smell of myself, which is probably very distasteful to everyone else.

He crouches down, and I wait to be smacked again, empty-headed. But it isn't him, it's her. "What are you doing here?" she asks. She probably means how did you come here, but I find myself wondering, what am I doing here? Looking for work. Trying to get passage home. But home is gone, should never have existed in the first place.

What does any person do in a lifetime? I give her an answer out of the Proverbs. "Putting off death," I say. "Go away, before you complicate my task— you people have done enough to me."

She looks unhappy. Cousins are like that, a sentimental people. "If I could help you, I would," she says.

"I know," I say, "but your help would make me need you. And then I would be just one more local on one more backward world." Everywhere the Cousins go across the sky, it's the same. Wanji used to tell us about her people, about the Cousins. About other worlds like ours. Where two cultures meet, she said, one of them usually gives way.

The Cousin searches through her pockets, puts a coin, a rectangular silver piece, in the dust. I wait, not moving, until they go on.

I pick up the coin. A proud person would throw it after her. I'm not proud, I'm hungry. I take it.

In the market, it's rabbit and duck day— kids herding ducks with long switches, cages of rabbits for sale, hanging next to that cheap old staple, thekla lizard drying in strips. I dodge past tallgrass poles with craken-dyed cloth hanging startling yellow, and cut through between two vegetable stands. Next to the hiring area, they're grilling stabos jerky on sticks, and selling pineapple slices dipped in saltwater to make them sweeter.

I use the Cousin's silver to buy noodles and red peanut paste, spicy with proyakapiti, and I eat slowly. I'm three days empty of food, and if I eat too fast, I'll be sick. I learned about going without food during a campaign, when I first started soldiering. On the long walk to Bashtoy. I know all about the different kinds of hunger; the first sharp stabs of appetite, then the strong hunger, how your stomach hurts after awhile, and then how you forget, and then how hunger comes back, like swollen joints in an old woman. And how it wears you down, how you become tired and stupid, and how then finally it leaves you altogether, and your jaw bone softens until your teeth rock in their sockets, and you have been hungry so long you don't know what it means anymore.

The yammerhead is on the other side of the hiring area, still going on about how the guilds monopolize the Cousins. How the guilds were nothing until ten years ago, when the Cousins came and brought magic, and then no one could trade without permission of the guild. I close my eyes, feeling sleepy after food, and I can see the place where I grew up. I was born in Sckarline, a magic town. I remember the white houses, the power station where Ayuedesh taught boys to cook stabos manure and get swamp air from it, then turned that into power that sang through copper and made light. At night, we had light for three or four dine after sunset. Phrases in the lingua the Cousins speak, Appropriate Technology. I am lost in Sckarline, looking for my mother, for kin. I see Trevin, and I follow him. He's way ahead, in leggings, in dark blue with fur on his shoulders. But the way he leads me is wrong, the buildings are burned, just blackened crossbeams jutting up, he is leading me toward—

"I'm looking for a musician." I jerk awake.

A flat-faced southerner waiting for hire says, "Musicians are over there." People who wait here are like me, looking for anything.

A portly man with a wine-colored robe says, "I'm looking for a musician who knows a little about swords."

"What kind of musician?" I ask. I always talk quietly, it's a failing, and the portly man doesn't hear me. He cocks his head.

"What kind of musician?" the flat-faced southerner repeats.

"Doesn't matter." The portly man shrugs, hawks so loudly it sounds as if he's clearing his tokking head, and spits.

Tokking southerners. They spit all the time, it drives me crazy. I hear them clear their throat, and I cringe and start looking to step out of the way. Heth knows I'm not squeamish, but they all do it, men, women, children.

"Sikha," the portly man offers. A sikha is a kind of southern lute, only they pick the strings on the neck as well as the ones on the body.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Good New Stuff»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Good New Stuff» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Good New Stuff» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.