Стивен Бакстер - The Good New Stuff

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Стивен Бакстер - The Good New Stuff» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2002, ISBN: 2002, Издательство: St. Martin's Griffin, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

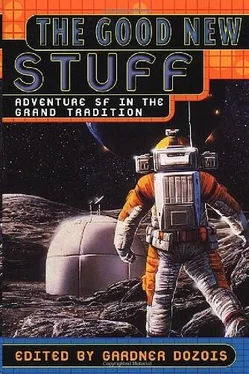

- Название:The Good New Stuff

- Автор:

- Издательство:St. Martin's Griffin

- Жанр:

- Год:2002

- ISBN:0-312-26456-9

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Good New Stuff: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Good New Stuff»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Good New Stuff — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Good New Stuff», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The Good New S T U F F

Adventure SF in the Grand Tradition

Edited by Gardner Dozois

For Isabella Marie Amelio Casper — the good new stuff.

Preface

"They don't write 'em like that anymore," you often hear people say, talking about fast-paced, no-holds-barred, flat-out adventure stories, stories drenched with color, wonder, and action, stories that take us to far worlds for adventures of a sort that could not be encountered on our familiar, present-day Earth, stories that bring us face-to-face with strange dangers and even stranger wonders— but, actually, they do still write stories like that!

Yes, they really do. Don't listen to the voices that say you can't find anything like that anymore— they're the voices of people so lost in nostalgia for the stories of their youth that they can't look around them and see what's happening right in front of their own eyes. If they did look around, they'd find that the space adventure story is not only alive and well here at the end of the nineties, it's flourishing.

As I hope to demonstrate in this anthology, you can still find science fiction adventure stories today every bit as wild and woolly and mind-blowing as anything from the old pulp days, stories as full of swashbuckling action, dash, and élan as any of the Planetary Romances from the old Planet Stories and Thrilling Wonder Stories, stories just as full of cosmic sweep and scale and grandeur and the immense, sun-shattering, planet-busting clash of titanic forces in conflict as anything from the old "Superscience" days of the thirties when Edmond Hamilton was earning his nickname of "World-Wrecker Hamilton" (except with much more accurate, up-to-date, cutting-edge science!).

Adventure writing is not the only sort of science fiction there is, of course, or the only thing science fiction does well, and never has been. Science fiction can be serious-minded and substantial and profound; it can be a window on worlds we'd never otherwise see and people and creatures we'd never otherwise know; it can provide us with insights into the inner workings of our society that are difficult to gain in any other way, grant us perspectives into social mores and human nature itself mostly otherwise unreachable; it can be an invaluable tool with which to take preconceived notions and received wisdom to pieces and reassemble them into something new; it can prepare us for the inevitable and sometimes dismaying changes ahead of us, helping to buffer us against the winds of Future Shock— but sometimes it's just fun.

Sometimes it's "just" pure entertainment (with any more serious implications or troubling social issues— and they do get raised, even in the most seemingly insubstantial of stories— largely left to be dealt with in the subtext), adventure writing as vivid and entertaining as any that has ever been written in any genre anywhere.

Although adventure writing is often looked down on by critics (it's hard even to think of the phrase adventure writing without automatically adding the prefix mere, since that's the way it's almost always referred to) or ignored completely, it's no more but certainly no less valid and valuable than any other kind of science fiction. It's something that's always been part of the palette of the science fiction genre as well, ever since the days of Hugo Gernsback's Amazing Stories in the late twenties, when the specific science fiction adventure story began to precipitate out from the larger and older tradition of the generalized pulp adventure story— often Lost World/Lost Race tales— that goes all the way back into the middle of the nineteenth century. (Although the SF adventure story has always had— and still has— other branches as well, the Space Adventure story or the Space Opera, of one subvariety or another, remains to this day probably the most characteristic sort of SF adventure tale, the form that slowly emerged as being most specific to science fiction, and that's the kind of story I've primarily stuck with for this anthology.)

The previous anthology in this series, The Good Old Stuff, published in 1998, traced the development of the genre space adventure tale, from its beginnings in the Gernsback magazines through the "Superscience" era of the thirties and early forties (the First Great Age of the Space Opera, when writers such as E. E. "Doc" Smith, Ray Cummings, Raymond Z. Gallun, Edmond Hamilton, John W. Campbell Jr., Jack Williamson, Clifford D. Simak, and others developed and refined a form of adventure tale specific to science fiction), and on through the years from the mid-forties to the mid-sixties, the Second Great Age of the Space Opera, when writers such as A. E. van Vogt, L. Sprague de Camp, James H. Schmitz, Murray Leinster, Leigh Brackett, Jack Vance, Poul Anderson, Gordon R. Dickson, and H. Beam Piper would add an increased social-political sophistication and an increase in line-by-line writing craft to the form, a trend taken to new heights of complexity, flamboyance, and vividness by writers such as Cordwainer Smith, Alfred Bester, Frank Herbert, Robert A. Heinlein, Brian W. Aldiss, Larry Niven, Ursula K. Le Guin, Roger Zelazny, Samuel R. Delany, James Tiptree, Jr., and many others.

By the late sixties and early seventies, however, perhaps because of the prominence of the "New Wave" revolution in SF, which concentrated both on introspective, stylistically "experimental" work and work with more immediate sociological and political "relevance" to the tempestuous social scene of the day, perhaps because of scientific proof that the other planets of the solar system were not likely abodes for life (and so, it seemed, not interesting settings for adventure stories), perhaps because the now more widely understood limitations of Einsteinian relativity had come to make the idea of far-flung interstellar empires seem improbable at best, science fiction as a genre was tending to turn away from the Space Adventure tale. Although it would never disappear completely, it had become widely regarded as outmoded and déclassé; the radical new writers of the generation just about to rise to prominence would collectively produce less adventure SF, particularly Space Opera, than any other comparable generational group of authors, and there would be less Space Adventure stuff written in the following ten years or so than in any other comparable period in SF history. By far the majority of work published during this period would be set on Earth, often in the near future— even the solar system had been largely deserted as a setting for stories, let alone the distant stars. Although stalwarts such as Poul Anderson and Jack Vance and Larry Niven continued to soldier on throughout those years, it was a common— and frequently expressed— opinion that Space Opera was dead.

But by the late seventies and early eighties, new writers such as John Varley, George R.R. Martin, Bruce Sterling, Michael Swanwick, Vernor Vinge, and others would begin to become interested in the Space Adventure again, reinvented to better fit the aesthetic style and tastes of the day. And by the nineties, a whole new boom in Baroque Space Opera would be underway, on both sides of the Atlantic (there are some slight but perceptible differences in flavor between the New British Space Opera and the New American Space Opera, although they clearly are responses to the same evolutionary impetus— and, as was also true of the New Wave, which also manifested itself in slightly different forms on either side of the ocean, the similarities are far more significant than the differences are), fueled by authors such as Iain M. Banks, Dan Simmons, Orson Scott Card, C. J. Cherryh, Gregory Benford, Greg Bear, Colin Greenland, Paul J. McAuley, Alexander Jablokov, Stephen Baxter, Walter Jon Williams, Stephen R. Donaldson, John Barnes, Lois McMaster Bujold, Charles Sheffield, Eleanor Arnason, Peter F. Hamilton, and a dozen others, ushering in the Third Great Age of Space Opera.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Good New Stuff»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Good New Stuff» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Good New Stuff» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.