Стивен Бакстер - The Good New Stuff

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Стивен Бакстер - The Good New Stuff» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2002, ISBN: 2002, Издательство: St. Martin's Griffin, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

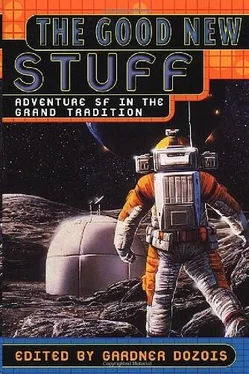

- Название:The Good New Stuff

- Автор:

- Издательство:St. Martin's Griffin

- Жанр:

- Год:2002

- ISBN:0-312-26456-9

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Good New Stuff: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Good New Stuff»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Good New Stuff — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Good New Stuff», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Which brings us into the territory of the book you hold in your hands, The Good New Stuff.

Even having decided on the territory that I would cover in this volume, though (the mid-seventies to the present day), I found, as is usually the case with these retrospective anthologies, that there were many more stories that I would have liked to use than I had room to use. Some arbitrary decisions clearly needed to be made to winnow the mass of potential stories down to a usable number, and, arbitrarily, I made them.

Most of these judgment calls are subjective, again as always. While there's often plenty of action in a William Gibson story, for instance, action alone is not the only criterion, and somehow Cyberpunk doesn't feel like adventure writing to me— too intense, too noir-ish, too gloomy (plus the fact that almost all cyberpunk writing, or the bulk of it, anyway, takes place on Earth in the relatively near future). So, arbitrarily, I decided to omit Cyberpunk stories from consideration, although it cost me first-rate authors from Gibson to Pat Cadigan to Lewis Shiner (Bruce Sterling gets in, but for his earlier, more Space Opera-ish work, not his later cyberpunk and post-cyberpunk stuff). Similarly, Military SF, although concerned largely with the exploits of Space Mercenaries and usually chockablock with battle scenes, doesn't feel right to me either— too narrowly specialized, and too often easily recognized as only Horatio Hornblower stories "translated" into science fiction terms, or thinly disguised recastings of Vietnam War or World War II scenarios. Lucius Shepard's stuff always has strong action elements, but it's usually on the borderland of horror fiction as well, or at least partakes of that aesthetic tone, and again that was not the "flavor" I was subjectively groping for (and again, the vast majority of Shepard's stories take place on Earth, or in interconnecting fantasy realms). So all of that was out as well.

The last major judgment call I made was even more subjective. Parallel with the new boom in Space Opera has been a boom in the "Hard Science" story, also reinvented to fit the styles and prejudices of the times better, and although there are many similarities between the two forms, and the reader who likes one is at least fairly likely to like the other, and although the situation is complicated by the fact that many authors have a foot in both camps, sometimes producing one kind of thing and sometimes another, I still thought that I could discern enough differences between the two styles to assign writers, arbitrarily, to one camp or the other. Stephen Baxter, Greg Egan, Greg Benford, Brian Stableford, and Paul J. McAuley, for instance, all write some of the hardest SF around, but somehow some of what Baxter and Benford and McAuley are doing strikes me as being legitimately classifiable as Space Opera, while what Egan and Stableford are doing does not. So no Egan or Stableford, even though they're excellent writers, and Egan in particular may be one of the best new writers of the nineties. (It's hard to articulate exactly what I'm instinctively basing this decision on, except perhaps a vague feeling that Space Opera or Space Adventure needs a quality of flamboyance, exaggeration, scope, swagger, outrageousness, overheatedness, perhaps even lurid excess— an over-the-top quality that the cool, mannered, cerebral, tightly controlled work of Egan and Stableford doesn't have.)

Some other decisions made themselves for me. Some of the major players in the current subgenre of the New Space Opera, such as Iain M. Banks and Colin Greenland, for instance, write almost no short fiction at all, and while others, such as Orson Scott Card, Dan Simmons, Stephen Donaldson, and C. J. Cherryh, do occasionally write short fiction, almost none of it is in the Space Adventure mode (almost all of Cherryh's short work is fantasy, for instance, as is the bulk of Donaldson's, while most of Simmons's is horror, and so on). And the practical difficulties involved in the assembling of an anthology necessitated the omission of still other stories, those, say, which had recently appeared in a competing anthology, or those for which the reprint rights were either encumbered or priced too high for me to be able to afford them on the limited budget I had to work with.

Even with all of those winnowing screens in place, I was still left with a mass of material too large to use. The constraints of a technically feasible book length dictated the omission of other stories, but I could easily have produced an anthology twice the length of this one, with little or no discernable letdown in quality, and I would have if I could have.

There are a lot of good new stories of this sort out there, and if you like this book, I urge you to go and seek them out on your own. They're not hard to find, believe me, in spite of what "they" say. All you have to do is open your eyes and look around you.

So, then, this is the Good New Stuff. Enjoy!

John Varley

GOODBYE, ROBINSON CRUSOE

John Varley appeared on the SF scene in 1974, and by the end of 1976— in what was a meteoric rise to prominence even for a field known for meteoric rises— he was already being recognized as one of the hottest new writers of the seventies. His first story, "Picnic on Nearside," appeared in 1974 in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, and was followed by as concentrated an outpouring of first-rate stories as the genre has ever seen, stories such as "Retrograde Summer," "In the Bowl," "Gotta Sing, Gotta Dance," "In the Hall of the Mountain King," "Equinoctial," "The Black Hole Passes," "Overdrawn at the Memory Bank," "The Phantom of Kansas," and many others: smart, bright, fresh, brash, audacious, effortlessly imaginative stories that seemed to suddenly shake the field out of its uneasy slumber like a wake-up call from a brand-new trumpet. It's hard to think of a group of short stories that has had a greater, more concentrated impact on the field, with the exception of Robert Heinlein's early work for John W. Campbell's Astounding, or perhaps Roger Zelazny's early stories in the mid-sixties (maybe a better example anyway, since, although Heinlein has always been one of Varley's major influences, his early Eight Worlds stuff in some ways had more in common with Zelazny, if only in that quality of good-natured effrontery and easy ostentation, and the almost insolent you-ain't-seen-nothing-yet ease and fecundity of his invention). By 1978, largely because of Varley's work, it would be possible for Algis Budrys to say (in the introduction to Varley's first collection, appropriately enough), "There is beginning to be, in other words, yet another new SF: vigorous, relevant, richer than ever" — a statement that would have been inconceivable a few years before, in the dull gray doldrums that had been left behind after the ferocious tempest of the New Wave Era had blown itself out and died away to stillness.

Varley was one of the first new writers to become interested in the solar system again, after several years in which it had been largely abandoned as a setting for stories because the space probes of the late sixties and early seventies had "proved" that it was nothing but an "uninteresting" collection of balls of rock and ice, with no available abodes for life— dull as a supermarket parking lot. Instead, Varley seemed to find the solar system lushly romantic just as it was, lifeless balls of rock and all (and this was even before the later Pioneer probes to the Jupiter and Saturn systems had proved the solar system to be a lot more surprising than people thought that it was). He makes this obvious in "In the Bowl," where he specifically invokes the richly romantic Venus of the Planet Stories days (and of Heinlein's Between Planets, which is even more specifically referenced), describing the human settlements of Venus as places of "steamy swamps and sleazy hotels" where you can "hunt the prehistoric monsters that wallow in the field marshes that are just a swamp-buggy ride out of town," or rub shoulders in the teeming streets with the "eight-legged dragons with eyestalks" who go lumbering by… and then, when the tourists go home, they shut all that off, all the Planet Stories dreams that are just there to amuse the rubes, and then "the place reverts to an ordinary cluster of silvery domes sitting in darkness and eight-hundred-degree temperature." The remarkable thing here, the revolutionary thing, is that Varley finds Venus more romantic once the pulp Planet Stories dreams are switched off and you're left with the uncompromising reality of Venus to deal with instead— finds it more romantic because it's an airless hellhole of eight-hundred-degree temperature and deadly crushing pressure, completely and totally unlike the Earth, instead of the ersatz copy of Earth in the dinosaur age that had been the dream of earlier writers. This is an aesthetic shift in perception that will go ringing on down through the eighties and nineties in the work of writers such as G. David Nordley, Stephen Baxter, and a dozen others.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Good New Stuff»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Good New Stuff» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Good New Stuff» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.