“Not just a springtime; it’s an interstadial time,” Willy McGilly stated accurately. “I’ve noticed that about them in other places. It’s old green season in their voices, green season between the ice.”

The room was lit only by hanging lamps. They had a flicker to them. They were not electric.

“There’s a lot of the gas-light era in this place,” Arpad gave the opinion, “but the lights aren’t gas lights either.”

“No, they’re hanging oil lamps,” Velikof said. “An amusing fancy just went through my head that they might be old whale-oil lamps.”

“Girl, what do you burn in the hanging lamps?” Willy McGilly asked her.

“Catfish oil,” she said in the resonant voice that had a touch of the green interstadial time in it. And catfish oil burns with a clay-colored flame.

“Can you bring us drinks while we wait?” Velikof of the massive head asked.

“They’re fixing them for you now,” the girl said. “I’ll bring them after a while.”

Meanwhile on the old pool table the Comet was beating the hairy man at rotation. Nobody could beat the Comet at rotation.

“We came here looking for strange creatures,” Arpad said in the direction of the girl. “Do you know anything about strange creatures or people, or where they can be found?”

“You are the only strange people who have come here lately,” she told them. Then she brought their drinks to them, three great sloshing clay cups or bulbous stems that smelled strongly of river, perhaps of interstadial river. She set them in front of the eminents with something like a twinkle in her eyes; something like, but much more. It was laughing lightning flashing from under the ridges of that pretty head. She was awaiting their reaction.

Velikof cocked a big deep eye at his drink. This itself was a feat. Other men hadn’t such eyes, or such brows above them, as had Velikof Vonk. They took a bit of cocking, and it wasn’t done lightly. And Velikof grinned out of deep folk memory as he began to drink. Velikof was always strong on the folk memory bit.

Arpad Arkabaranan screamed, rose backward, toppled his chair, and stood aghast while pointing a shaking finger at his splashing clay cup. Arpad was disturbed.

Willy McGilly drank deeply from his own stirring vessel.

“Why, it’s Green Snake Snorter!” he cried in amazement and delight. “Oh drink of drinks, thou’re a pleasure beyond expectation! They used to serve it to us back home, but I never even hoped to find it here. What great thing have we done to deserve this?”

He drank again of the wonderful splashing liquor while the spray of it filled the air. And Velikof also drank with noisy pleasure. The girl righted Arpad’s chair, put Arpad into it again with strong hands, and addressed him powerfully to his cresting breaker. But Arpad was scared of his lively drink. “It’s alive, it’s alive,” was all that he could jabber. Arpad Arkabaranan specialized in primitives, and primitives by definition are prime stuff. But there wasn’t, now in his moment of weakness, enough prime stuff in Arpad himself to face so pleasant and primitive a drink as this.

The liquid was sparkling with bright action, was adequately alcoholic, something like choc beer, and there was a green snake in each cup. (Velikof in his notebook states that they were green worms of the species vermis ebrius viridis, but that is only a quibble. They were snakelike worms and of the size of small snakes, and we will call them snakes.)

“Do get with it, Arpad,” Willy McGilly cried. “The trick is to drink it up before the snake drinks it. I tell you though that the snakes can discern when a man is afraid of them. They’ll fang the face off a man who’s afraid of them.”

“Ah, I don’t believe that I want the drink,” Arpad declared with sickish grace. “I’m not much of a drinking man.”

So Arpad’s green snake drank up his Green Snake Snorter, noisily and greedily. Then it expired—it breathed out its life and evaporated. That green snake was gone.

“Where did he go?” Arpad asked nervously. He was still uneasy about the business.

“Back to the catfish,” the girl said. “All the snakes are spirits of catfish just out for a little ramble.”

“Interesting,” Velikof said, and he noted in his pocket notebook that the vermis ebrius viridis is not a discrete species of worm or snake, but is rather spirit of catfish. It is out of such careful notation that science is built up.

“Is there anything noteworthy about Boomer Flats?” Velikof asked the girl then. “Has it any unique claim to fame?”

“Yes,” the girl said. “This is the place that the comets come back to.”

“Ah, but the moths have eaten the comets,” Willy McGilly quoted from the old epic.

The girl brought them three big clay bowls heaped with fish eggs, and these they were to eat with three clay spoons. Willy McGilly and Dr. Velikof Vonk addressed themselves to the rich meal with pleasure, but Arpad Arkabaranan refused.

“Why, it’s all mixed with mud and sand and trash,” he objected.

“Certainly, certainly, wonderful, wonderful,” Willy McGilly slushed out the happy words with a mouth full of delicious goop. “I always thought that something went out of the world when they cleaned up the old shantytown dish of shad roe. In some places they cleaned it up; not everywhere. I maintain that roe at its best must always have at least a slight tang of river sewage.”

But Arpad broke his clay spoon in disgust. And he would not eat. Arpad had traveled a million miles in search of it but he didn’t know it when he found it; he hadn’t any of it inside him so he missed it.

One of the domino players at a near table (the three eminents had noticed this some time before but had not fully realized it) was a bear. The bear was dressed as a shabby man, he wore a big black hat on his head; he played dominos well; he was winning.

“How is it that the bear plays so well?” Velikof asked.

“He doesn’t play at all well,” Willy McGilly protested. “I could beat him. I could beat any of them.”

“He isn’t really a bear,” the girl said. “He is my cousin. Our mothers, who were sisters, were clownish. His mother licked him into the shape of a bear for fun. But that is nothing to what my mother did to me. She licked me into pretty face and pretty figure for a joke, and now I am stuck with it. I think it is too much of a joke. I’m not really like this, but I guess I may as well laugh at me just as everybody else does.”

“What is your name?” Arpad asked her without real interest.

“Crayola Catfish.”

But Arpad Arkabaranan didn’t hear or recognize the name, though it had been on a tape that Dr. Velikof Vonk had played for them, the same tape that had really brought them to Boomer Flats. Arpad had now closed his eyes and ears and heart to all of it.

The hairy man and the Comet were still shooting pool, but pieces were still falling off the Comet.

“He’s diminishing, he’s breaking up,” Velikof observed. “He won’t last another hundred years at that rate.”

Then the eminents left board and room and the Cimarron Hotel to go looking for ABSMs who were rumored to live in that area.

ABSM is the code name for the Abominable Snowman, for the Hairy Woodman, for the Wild Man of Borneo, for the Sasquatch, for the Booger-Man, for the Ape-Man, for the Bear-Man, for the Missing Link, for the nine-foot-tall Giant things, for the living Neanderthals. It is believed by some that all of these beings are the same. It is believed by most that these things are no thing at all, no where, not in any form.

And it seemed as if the most were right, for the three eminents could not find hide nor hair (rough hide and copious hair were supposed to be marks by which the ABSMs might be known) of the queer folks anywhere along the red bank of the Cimarron River. Such creatures as they did encounter were very like the shabby and untalkative creatures they had already encountered in Boomer Flats. They weren’t an ugly people: they were pleasantly mud-homely. They were civil and most often they were silent. They dressed something as people had dressed seventy-five years before that time—as the poor working people had dressed then. Maybe they were poor, maybe not. They didn’t seem to work very much. Sometimes a man or a woman seemed to be doing a little bit of work, very casually.

Читать дальше

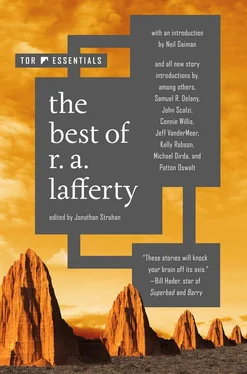

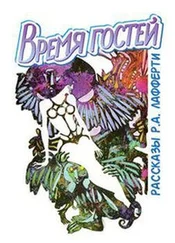

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Дни, полные любви и смерти. Лучшее [сборник litres]](/books/385123/rafael-lafferti-dni-polnye-lyubvi-i-smerti-luchshe-thumb.webp)

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Лучшее [Сборник фантастических рассказов]](/books/401500/rafael-lafferti-luchshee-sbornik-fantasticheskih-ra-thumb.webp)