Then Dr. Velikof Vonk had come onto a tape in a bunch of anthropological tapes, and the tape contained sequences like this:

“What do they do when the river floods?”

“Ah, they close their noses and mouths and ears with mud, and they lie down with big rocks on their breasts and stay there till the flood has passed.”

“Can they be taught?”

“Some of the children go to school, and they learn. But when they are older then they stay at home, and they forget.”

“What sort of language do they talk?”

“Ah, they don’t seem to talk very much. They keep to themselves. Sometimes when they talk it is just plain Cimarron Valley English.”

“What do they eat?”

“They boil river water in mud clay pots. They put in wild onions and greenery. The pottage thickens then, I don’t know how. It gets lumps of meat or clay in it, and they eat that too. They eat frogs and fish and owls and thicket filaments. But mostly they don’t eat very much of anything.”

“It is said that they aren’t all of the same appearance. It is even said that they are born, ah, shapeless, and that—ah—could you tell me anything about that?”

“Yeah. They’re born without much shape. Most of them never do get much shape. When they have any, well actually their mothers lick them into shape, give them their appearance.”

“It’s an old folk tale that bears do that.”

“Maybe they learned it from the bears then, young fellow. There’s quite a bit of bear mixture in them, but the bears themselves have nearly gone from the flats and thickets now. More than likely the bears learned it from them. Sometimes the mothers lick the cubs into the shape of regular people for a joke.”

“That is the legend?”

“You keep saying legend. I don’t know anything about legend. I just tell you what you ask me. I’ll tell you a funny one, though. One of the mothers who was getting ready to bear happened to get ahold of an old movie magazine that some fishers from Boomer had left on the river edge. There was a picture in it of the prettiest girl that anyone ever saw, and it was a picture of all of that girl. This mother was tickled by that picture. She bore a daughter then, and she licked her into the shape and appearance of the girl in the movie magazine. And the girl grew up looking like that and she still looks like that, pretty as a picture. I don’t believe the girl appreciates the joke. She is the prettiest of all the people, though. Her name is Crayola Catfish.”

“Are you having me, old fellow? Have those creatures any humor?”

“Some of them tell old jokes. John Salt tells old jokes. The Licorice Man tells really old jokes. And man, does the Comet ever tell old jokes!”

“Are the creatures long-lived?”

“Long-lived as we want to be. The elixir comes from these flats, you know. Some of us use it, some of us don’t.”

“Are you one of the creatures?”

“Sure, I’m one of them. I like to get out from it sometimes though. I follow the harvests.”

This tape (recorded by an anthropology student at State University who, by the way, has since busted out of anthropology and is now taking hotel and restaurant management) had greatly excited the eminent scientist Dr. Velikof Vonk when he had played it, along with several hundred other tapes that had come in that week from the anthropology circuit. He scratched his—(no he didn’t, he didn’t have one)—he scratched his jowl and he phoned up the eminent scientists Arpad Arkabaranan and Willy McGilly.

“I’ll go, I’ll go, of course I’ll go,” Arpad had cried. “I’ve traveled a million miles in search of it, and should I refuse to go sixty? This won’t be it, this can’t be it, but I’ll never give up. Yes, we’ll go tomorrow.”

“Sure, I’ll go,” Willy McGilly said. “I’ve been there before, I kind of like those folks on the flats. I don’t know about the biggest catfish in the world, but the biggest catfish stories in the world have been pulled out of the Cimarron River right about at Boomer Flats. Sure, we’ll go tomorrow.”

“This may be it,” Velikof had said. “How can we miss it? I can almost reach out and scratch it on the nose from here.”

“You’ll find yourself scratching your own nose, that’s how you’ll miss it. But it’s there and it’s real.”

“I believe, Willy, that there is a sort of amnesia that has prevented us finding them or remembering them accurately.”

“Not that, Velikof. It’s just that they’re always too close to see.”

So the next day the three eminent scientists drove over from T-Town to come to Boomer Flats. Willy McGilly knew where the place was, but his pointing out of the way seemed improbable: Velikof was more inclined to trust the information of people in Boomer. And there was a difficulty there.

People kept saying, “This is Boomer. There isn’t exactly any place called Boomer Flats.” Boomer Flats wasn’t on any map. It was too small even to have a post office. And the Boomer people were exasperating in not knowing about it or knowing the way to it.

“Three miles from here, and you don’t know where it is?” Velikof asked one of them angrily.

“I don’t even know that it is,” the Boomer man had said in his own near anger. “I don’t believe that there is such a place.”

Finally, however, other men told the eminent scientists that there sort of was such a place, sort of a place. Sort of a road going to it too. They pointed out the same improbable way that Willy McGilly had pointed out.

The three eminents took the road. The flats hadn’t flooded lately. The road was sand, but it could be negotiated. They came to the town, to the sort of town, in the ragged river flats. There was such a place. They went to the Cimarron Hotel which was like any hotel anywhere, only older. They went into the dining room, for it was noon.

It had tables, but it was more than a dining room. It was a common room. It even had intimations of old elegance in blued pier mirrors. There was a dingy bar there. There was a pool table there, and a hairy man was playing rotation with the Comet on it. The Comet was a long gray-bearded man (in fact, comet means a star with a beard) and small pieces were always falling off him. Clay-colored men with their hats on were playing dominos at several of the tables, and there were half a dozen dogs in the room. Something a little queer and primordial about those dogs! Something a little queer and primordial about the whole place!

But, as if set to serve as distraction, there was a remarkably pretty girl there, and she might have been a waitress. She seemed to be waiting, either listlessly or profoundly, for something.

Dr Velikof Vonk twinkled his deep eyes in their orbital caves: perhaps he cogitated his massive brain behind his massive orbital ridges: and he arrived, by sheer mentality, at the next step.

“Have you a menu, young lady?” he asked.

“No,” she answered simply, but it wasn’t simple at all. Her voice didn’t go with her prettiness. It was much more intricate than her appearance, even in that one syllable. It was powerful, not really harsh, deep and resonant as caverns, full and timeless. The girl was big-boned beneath her prettiness, with heavy brindled hair and complex eyes.

“We would like something to eat,” Arpad Arkabaranan ventured. “What do you have?”

“They’re fixing it for you now,” the girl said. “I’ll bring it after a while.”

There was a rich river smell about the whole place, and the room was badly lit.

“Her voice is an odd one,” Arpad whispered in curious admiration. “Like rocks rolled around by water, but it also has a touch of springtime in it, springtime of a very peculiar duality.”

Читать дальше

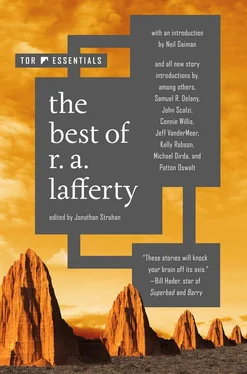

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Дни, полные любви и смерти. Лучшее [сборник litres]](/books/385123/rafael-lafferti-dni-polnye-lyubvi-i-smerti-luchshe-thumb.webp)

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Лучшее [Сборник фантастических рассказов]](/books/401500/rafael-lafferti-luchshee-sbornik-fantasticheskih-ra-thumb.webp)