There was the dead white shape of Mycelium masses, the grotesqueness of Agaricus, the deformity of Deadly Amanita and of Morel. The gray-milky Lactarius glowed like light-less lanterns in the dark; there was the blue-white of the Deceiving Clitocybe and the yellow-white of the Caesar Agaric. There was the insane ghost-white of the deadliest and queerest of them all, the Fly Amanita, and a mole was gathering this.

“Mole, bring Sky for the Thing Serene, for the Minions tall and the Airy Queen,” Welkin jangled. She was still high on Sky, but it had begun to leave her a little and she had the veriest touch of the desolate sickness.

“Sky for the Queen of the buzzing drones, with her hollow heart and her hollow bones,” the Sky-Seller intoned hollowly.

“And fresh, Oh I want it fresh, fresh Sky!” Welkin cried.

“With these creatures there is no such thing as fresh,” the Sky-Seller told her. “You want it stale, Oh so stale! Ingrown and aged and with its own mold grown moldy.”

“Which is it?” Welkin demanded. “What is the name of the one you gather it from?”

“The Fly Amanita.”

“But isn’t that simply a poisonous mushroom?”

“It has passed beyond that. It has sublimated. Its simple poison has had its second fermenting into narcotic.”

“But it sounds so cheap that it be merely narcotic.”

“Not merely narcotic. It is something very special in narcotic.”

“No, no, not narcotic at all!” Welkin protested. “It is liberating, it is world-shattering. It is Height Absolute. It is motion and detachment itself. It is the ultimate. It is mastery.”

“Why, then it is mastery, lady. It is the highest and lowest of all created things.”

“No, no,” Welkin protested again, “not created. It is not born, it is not made. I couldn’t stand that. It is the highest of all uncreated things.”

“Take it, take it,” the Sky-Seller growled, “and be gone. Something begins to curl up inside me.”

“I go!” Welkin said, “And I will be back many times for more.”

“No, you will not be. Nobody ever comes back many times for Sky. You will be back never. Or one time. I think that you will be back one time.”

They went up again the next morning, the last morning. But why should we say that it was the last morning? Because there would no longer be divisions or days for them. It would be one last eternal day for them now, and nothing could break it.

They went up in the plane that had once been named Shrike and was now named Eternal Eagle . The plane had repainted itself during the night with new name and new symbols, some of them not immediately understandable. The plane snuffled Sky into its manifolds, and grinned and roared. And the plane went up!

Oh! Jerusalem in the Sky! How it went up!

They were all certainly perfect now and would never need Sky again. They were Sky .

“How little the world is!” Welkin rang out. “The towns are like fly-specks and the cities are like flies.”

“It is wrong that so ignoble a creature as the Fly should have the exalted name,” Icarus complained.

“I’ll fix that,” Welkin sang. “I give edict: that all the flies on Earth be dead!” And all the flies on Earth died in that instant.

“I wasn’t sure you could do that,” said Joseph Alzarsi. “The wrong is righted. Now we ourselves assume the noble name of Flies. There are no Flies but us!”

The five of them, including the pilot, Ronald Kolibri, stepped chuteless out of the Eternal Eagle . “Will you be all right?” Ronald asked the rollicking plane. “Certainly,” the plane said. “I believe I know where there are other Eternal Eagles . I will mate.”

It was cloudless, or else they had developed the facility of seeing through clouds. Or perhaps it was that, the Earth having become as small as a marble, the clouds around it were insignificant.

Pure light that had an everywhere source! (The sun also had become insignificant and didn’t contribute much to the light.) Pure and intense motion that had no location reference. They weren’t going anywhere with their intense motion (they already were everywhere, or at the supercharged center of everything).

Pure cold fever. Pure serenity. Impure hyper-space passion of Karl Vlieger, and then of all of them; but it was purely rampant at least. Stunning beauty in all things along with a towering cragginess that was just ugly enough to create an ecstasy.

Welkin Alauda was mythic with nenuphars in her hair. And it shall not be told what Joseph Alzarsi wore in his own hair. An always-instant, a million or a billion years!

Not monotony, no! Presentation! Living sets! Scenery! The scenes were formed for the splinter of a moment; or they were formed forever. Whole worlds formed in a pregnant void: not spherical worlds merely, but dodeka-spherical, and those much more intricate than that. Not merely seven colors to play with, but seven to the seventh and to the seventh again.

Stars vivid in the bright light. You who have seen stars only in darkness be silent! Asteroids that they ate like peanuts, for now they were all metamorphic giants. Galaxies like herds of rampaging elephants. Bridges so long that both ends of them receded over the light-speed edges. Waterfalls, of a finer water, that bounced off galaxy clusters as if they were boulders.

Through a certain ineptitude of handling, Welkin extinguished the old sun with one such leaping torrent.

“It does not matter,” Icarus told her. “Either a million or a billion years had passed according to the timescale of the bodies, and surely the sun had already come onto dim days. You can always make other suns.”

Karl Vlieger was casting lightning bolts millions of parsecs long and making looping contact with clustered galaxies with them.

“Are you sure that we are not using up any time?” Welkin asked them with some apprehension.

“Oh, time still uses itself up, but we are safely out of the reach of it all,” Joseph explained. “Time is only one very inefficient method of counting numbers. It is inefficient because it is limited in its numbers, and because the counter by such a system must die when he has come to the end of his series. That alone should weigh against it as a mathematical system; it really shouldn’t be taught.”

“Then nothing can hurt us ever?” Welkin wanted to be reassured.

“No, nothing can come at us except inside time and we are outside it. Nothing can collide with us except in space and we disdain space. Stop it, Karl! As you do it that’s buggery.”

“I have a worm in my own tract and it gnaws at me a little,” the pilot Ronald Kolibri said. “It’s in my internal space and it’s crunching along at a pretty good rate.”

“No, no, that’s impossible. Nothing can reach or hurt us,” Joseph insisted.

“I have a worm of my own in a still more interior tract,” said Icarus, “the tract that they never quite located in the head or the heart or the bowels. Maybe this tract always was outside space. Oh, my worm doesn’t gnaw, but it stirs. Maybe I’m tired of being out of reach of everything.”

“Where do these doubts rise from?” Joseph sounded querulous. “You hadn’t them an instant ago, you hadn’t them as recently as ten million years ago. How can you have them now when there isn’t any now?”

“Well, as to that—” Icarus began—(and a million years went by)—“as to that I have a sort of cosmic curiosity about an object in my own past—”—(another million years went by)—“an object called world.”

“Well, satisfy your curiosity then,” Karl Vlieger snapped. “Don’t you even know how to make a world?”

“Certainly I know how, but will it be the same?”

Читать дальше

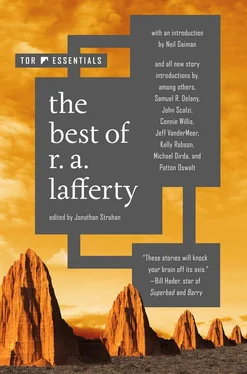

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Дни, полные любви и смерти. Лучшее [сборник litres]](/books/385123/rafael-lafferti-dni-polnye-lyubvi-i-smerti-luchshe-thumb.webp)

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Лучшее [Сборник фантастических рассказов]](/books/401500/rafael-lafferti-luchshee-sbornik-fantasticheskih-ra-thumb.webp)