There are, I know, many apparent glaring exceptions to the rule that only persons who are deficient or lacking in person or personality will contribute any creative content. Believe me, these exceptions are only apparent. There is something badly unbalanced in every one of them.

Carry it one step further, though. One of the legends, unwritten from the beginning and maybe unwritten forever, is about a Quest for the Perfect Thing. But it is really the quest for the normal thing. Can you find, anywhere in the world, behind or before or present, even one person who is really normal and reasonable and balanced and well-adjusted? This is the Perfect Thing, if it or he or she is ever found, and if ever found there will be no further need of any art or attempted art, good or bad.

Enough of such stuff, end of article, if this is an article. I am both facetious and serious in every written word here.

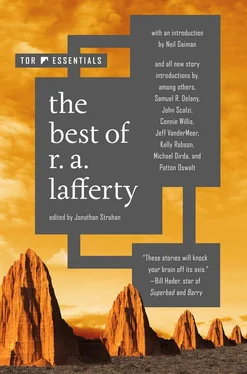

Introduction by Gwenda Bond

Reading an R. A. Lafferty story is always a bit of a trippy experience—a journey into the odder parts of experience, his perceptively askew perspective a looking glass all its own. But “Sky” is about an actual trip (or a few of them), with all the inspired psychedelia and questionable reality we expect—and desire—from a Lafferty story. The title’s Sky isn’t the airy horizon above us. No, it’s the unusual substance sold by the furry-handed “Sky-Seller” who can’t survive in sunlight (or thinks he can’t anyway) to ostensible main character Welkin Alauda.

A 1972 Hugo nominee, “Sky” sits at the intersection of the absurd and the transcendental. There are deadpan assurances of fantastical dangers: “You will burn,” Welkin told him. “Nobody burns so as when sunning himself on a cloud.” There is the observational commentary of some unseen but nonetheless present narrator on both the characters and the grim world that surrounds them; of Welkin we’re told “it was said that her bones were hollow and filled with air.” The Sky-Diving friends of Welkin discuss time and the universe, existence and falls through it, in perfect rose-colored stoner parlance. We sense the end of a journey coming as we read, and we know it will be quite a crash. Welkin wanders through caverns filled with Amanita mushroom varieties, deadly and hallucinogenic, gathered by not just the Sky-Seller but moles.

The results that follow this final trip linger with the reader. So enjoy this delightful trance of a tale, but, always remember, Sky has its dangers.

The Sky-Seller was Mr. Furtive himself, fox-muzzled, ferret-eyed, slithering along like a snake, and living under the Rocks. The Rocks had not been a grand place for a long time. It had been built in the grand style on a mephitic plot of earth (to transform it), but the mephitic earth had won out. The apartments of the Rocks had lost their sparkle as they had been divided again and again, and now they were shoddy. The Rocks had weathered. Its once pastel hues were now dull grays and browns.

The five underground levels had been parking places for motor vehicles when those were still common, but now these depths were turned into warrens and hovels. The Sky-Seller lurked and lived in the lowest and smallest and meanest of them all.

He came out only at night. Daylight would have killed him; he knew that. He sold out of the darkest shadows of the night. He had only a few (though oddly select) clients, and nobody knew who his supplier was. He said that he had no supplier, that he gathered and made the stuff himself.

Welkin Alauda, a full-bodied but light-moving girl (it was said that her bones were hollow and filled with air), came to the Sky-Seller just before first light, just when he had become highly nervous but had not yet bolted to his underground.

“A sack of Sky from the nervous mouse. Jump, or the sun will gobble your house!” Welkin sang-song, and she was already higher than most skies.

“Hurry, hurry!” the Sky-Seller begged, thrusting the sack to her while his black eyes trembled and glittered (if real light should ever reflect into them he’d go blind).

Welkin took the sack of Sky, and scrambled money notes into his hands which had furred palms. (Really? Yes, really.)

“World be flat and the Air be round, wherever the Sky grows underground,” Welkin intoned, taking the sack of Sky and soaring along with a light scamper of feet (she hadn’t much weight, her bones were hollow). And the Sky-Seller darted headfirst down a black well-shaft thing to his depths.

Four of them went Sky-Diving that morning, Welkin herself, Karl Vlieger, Icarus Riley, Joseph Alzarsi; and the pilot was—(no, not who you think, he had already threatened to turn them all in; they’d use that pilot no more)—the pilot was Ronald Kolibri in his little crop-dusting plane.

But a crop-duster will not go up to the frosty heights they liked to take off from. Yes it will—if everybody is on Sky. But it isn’t pressurized, and it doesn’t carry oxygen. That doesn’t matter, not if everybody is on Sky, not if the plane is on Sky too.

Welkin took Sky with Mountain Whizz, a carbonated drink. Karl stuffed it into his lip like snuff. Icarus Riley rolled it and smoked it. Joseph Alzarsi needled it, mixed with drinking alcohol, into his main vein. The pilot, Ronny, tongued and chewed it like sugar dust. The plane named Shrike took it through the manifold.

Fifty thousand feet—you can’t go that high in a crop-duster. Thirty below zero—ah, that isn’t cold! Air too thin to breathe at all—with Sky, who needs such included things as air?

Welkin stepped out, and went up, not down. It was a trick she often pulled. She hadn’t much weight; she could always get higher than the rest of them. She went up and up until she disappeared. Then she drifted down again, completely enclosed in a sphere of ice crystal, sparkling inside it and making monkey faces at them.

The wind yelled and barked, and the divers took off. They all went down, soaring and gliding and tumbling; standing still sometimes, it seemed; even rising again a little. They went down to clouds and spread out on them; dark-white clouds with the sun inside them and suffusing them both from above and below. They cracked Welkin’s ice-crystal sphere and she stepped out of it. They ate the thin pieces of it, very cold and brittle and with a tang of ozone. Alzarsi took off his shirt and sunned himself on a cloud.

“You will burn,” Welkin told him. “Nobody burns so as when sunning himself on a cloud.” That was true.

They sank through the black-whiteness of these clouds and came into the limitless blue concourse with clouds above and below them. It was in this same concourse that Hippodameia used to race her horses, there not being room for such coursers to run on Earth. The clouds below folded up and the clouds above folded down, forming a discrete space.

“We have our own rotundity and sphere here,” said Icarus Riley (these are their Sky-Diver names, not their legal names), “and it is apart from all worlds and bodies. The worlds and bodies do not exist for as long a time as we say that they do not exist. The axis of our present space is its own concord. Therefore, it being in perfect concord, Time stops.”

All their watches had stopped, at least.

“But there is a world below,” said Karl. “It is an abject world, and we can keep it abject forever if we wish. But it has at least a shadowy existence, and later we will let it fill out again in our compassion for lowly things. It is flat, though, and we must insist that it remain flat.”

“This is important,” Joseph said with the deep importance of one on Sky. “So long as our own space is bowed and globed, the world must remain flat or depressed. But the world must not be allowed to bow its back again. We are in danger if it ever does. So long as it is truly flat and abject it cannot crash ourselves to it.”

Читать дальше

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Дни, полные любви и смерти. Лучшее [сборник litres]](/books/385123/rafael-lafferti-dni-polnye-lyubvi-i-smerti-luchshe-thumb.webp)

![Рафаэль Лафферти - Лучшее [Сборник фантастических рассказов]](/books/401500/rafael-lafferti-luchshee-sbornik-fantasticheskih-ra-thumb.webp)