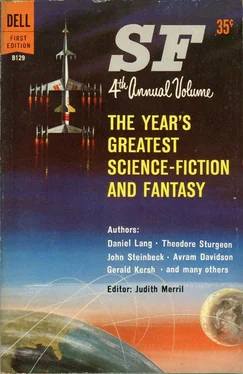

Judith Merril - The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Judith Merril - The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1959, Издательство: Dell, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1959

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Captain Phoebus and his submariners notwithstanding, one type of nutrition that is being seriously considered is about as far a cry from blueberry pie as can be imagined. This is the botanical group called the algae, one of the earth’s most primitive forms of vegetation. In many respects, algae would make the ideal food for the astronaut, though they might not appeal to his palate. Algae contain proteins, fats, and carbohydrates, and could easily be grown aboard the ship—in small tanks irradiated by intense light. Moreover, they might solve the difficult problem of disposing of human waste, by using it as fertilizer. And, to mention another of algae’s virtues, they can photosynthesize—that is, re-form the molecules of carbon dioxide breathed out by the space traveler, thereby releasing oxygen. Less than two months ago, during the world’s first international symposium on submarine and space medicine, which was held by the American Institute of Biological Sciences at the naval submarine base in Groton, Connecticut, some researchers reported the discovery of a new strain of algae that can increase itself by cell multiplication a thousandfold daily; the previous high had been eight times. The taste of algae, it might be mentioned, varies; one strain, for example, has a black-peppery tang, and another tastes something like mushrooms. “Algae have it all over pemmi-can,” one man who has sampled both told me. But he hadn’t eaten algae month after month in a spaceship.

This whole scheme of spaceship farming is patterned after nature’s cycle here on earth, where time and the sun’s energy, through the chemical changes they bring about, convert animal wastes and dead plants into crops. “What better method [of producing food] is there than to emulate the system already found in existence on the earth?” is a rhetorical question asked in “Closed Cycle Biological Systems for Space Feeding,” a paper put out by the Quartermaster Food and Container Institute for the Armed Forces, in Chicago. “Man will be supplied food, water and oxygen from biological and chemical systems. He will eat the food, turning out the same wastes in the spaceship that are produced on the face of the earth.” One expert I met, Dr. Harvey E. Savely, director of the Aero Medical Division of the Air Force Office of Scientific Research, confessed to me that the prospect of having our space men grow and harvest algae strikes him as anachronistic. “To think,” he said, “that we may develop so advanced a machine as a spaceship and then have to fall back on so primitive a calling as agriculture.”

Of all the strange experiences that may await the astronaut, none will be quite so strange, the experts agree, as weightlessness. This phenomenon will occur as soon as the spaceship reaches a speed at which the rocket’s centrifugal force cancels the pull of the earth’s gravity, and when it does, the space man, whether settling into orbit or making for Venus or Mars, will know for certain that he has arrived in outer space. He will weigh nothing. The air in his cabin will weigh nothing. The warm carbon dioxide he breaths out, being no lighter than the air in the cabin, will not rise, so he will have to exhale forcibly. Momentum, the force whirling the ship on its course, will rule its interior as well, and with possibly weird results. All objects that are not in some way fastened down—a map, a flashlight, a pencil—will float freely, subjecting the space man to a haphazard crossfire. If he were to drink water from an ordinary tumbler, the water might dash into his nostrils, float there, and drown him. Ordinary tumblers will not be used, however; plastic squeeze bottles will. (“The proper-size orifice is being worked out,” I was told by Major Henry G. Wise, of the Human Factors Division, Air Force Directorate of Research and Development.) Far more startling than the movement of objects, though, will be the space man’s own movements. Normally, in making a movement of any kind, a man has to overcome the body’s inertia plus its weight; a weightless man has only the inertia to overcome, and the chances are that it will take a long time for his muscles to grow accustomed to the fact. “What would be a normal step on earth would . . . send the ‘stepper’ sailing across the cabin or somersaulting wildly in the air,” the Air University Command and Staff School study declares. “A mere sneeze could propel the victim violently against the cabin wall and result in possible injury.”

Actually, very little is known about weightlessness. Until a few years ago, it was something that man had experienced only in very special circumstances, and then for no more than a fraction of a second—at the start of a roller coaster’s plunge, for example, or at the instant of going off a high diving board. With the man-in-space program moving along, however, weightlessness has been deliberately arranged in certain flights undertaken at the Air Force School of Aviation Medicine, in San Antonio; in these, jet planes, flying along a prescribed parabolic course, manage to escape the effects of gravity for as long as thirty seconds. The exposure to weightlessness, brief as it is, has had widely varying effects on the airmen. “The sensation can best be described as one of incredulity, or even slight amusement,” a colonel with a great deal of flying experience has reported, ascribing this reaction to “the incongruity of seeing objects and one’s own feet float free of the floor without any muscular effort.” Another airman, who was a gymnast in college, was reminded of “having started a back flip from a standing position and then become hung up part way over—looking toward the sky but not completing the flip.” The sensation, he said, gave him “no particular enjoyment or dislike”—only “a feeling of indifference.” Other airmen have found the experience extremely unpleasant—accompanied by nausea, sleepiness, weakness, sweating, and/or vertigo—and, to confuse matters, still others have discovered that their reactions differ on different flights. All told, one expert estimates, about a third of the subjects regard weightlessness as “definitely distressing,” while a fourth regard it as “not exactly comfortable.”

The experts realize, of course, that weightless voyages lasting a good deal longer than half a minute would have physical and mental results that can only be guessed at now. “Most probably, nature will make us pay for the free ride,” one scientist has said, almost superstitiously. For one thing, a long trip would raise hob with a man’s muscles. In any earthly condition of inactivity, no matter how extreme, they still have the job of resisting gravity, and without this they are bound to grow flabby. Moreover, the space man’s sense of balance would be thrown out of whack; this sense is governed by a liquid in our inner ear, and without gravity that liquid, floating freely in the chambers of the ear, could not be relied on to do its work. Not only would the space man be uncertain of where he was in his cabin at any particular moment, I learned from Lieutenant Colonel Robert Williams, a consultant in neurology and psychiatry to the Surgeon General, but he would run the risk of losing his “body image.” This image, Dr. Williams told me, is the deeply rooted conception that we all have of ourselves as a physical entity; it is one of the major constituents of our equanimity. “Without a body image,” he went on, “a person has difficulty in determining what is inside oneself and what is outside, in distinguishing one’s fantasy life from one’s real environment. In losing it, we face a possible complete disruption of personality.”

Assuming that the space traveler returns to earth with his personality undamaged, other difficulties may be in store for him. “A man who has been weightless for a couple of weeks would find it as hard to move around as a hospital patient taking his first steps after a long siege in bed,” Dr. Savely told me. “If he were to travel in a cooped-up posture over a long period of time—and, for all we know now, that may be the only way he can travel—the whole architecture of his skeleton might change. Of course, we simply cannot allow that to happen.” In view of such forebodings, it is not surprising that the man-in-space people are seeking to avoid weightlessness, altogether or in part, by developing an artificial substitute for gravity, but they don’t seem to have made much headway. According to one scheme, the space man’s cabin would be attached to the rocket by a long cable and would be swung around it continuously, thus creating a field of gravity that would restore the passenger’s weight and, presumably, his efficiency. Discussing this in the Scientific American, Dr. Heinz Haber, of the Air Force School of Aviation Medicine, guesses that it would work only as long as the passenger stood absolutely still. “Every voluntary movement,” he writes, “would give the traveler the peculiar illusion that he was being moved haphazardly.” Another approach would be to have the astronaut tread a magnetized floor in iron shoes, but Dr. Haber isn’t too sanguine about this one, either. Not only would the magnetism throw off the ship’s electronic instruments, he points out, but it would “probably add to the traveler’s confusion, for while his shoes would be attracted to the floor, his nonmagnetic body would not.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.