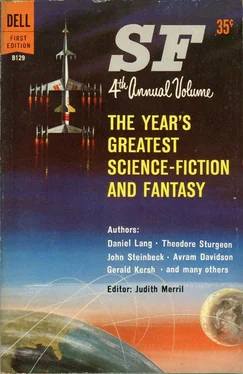

Judith Merril - The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Judith Merril - The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1959, Издательство: Dell, Жанр: Фантастика и фэнтези, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4

- Автор:

- Издательство:Dell

- Жанр:

- Год:1959

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4 — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

To Dr. Edson, the assistant to the director of Army Research and Development, the exploration of space presents itself not as a potential means of mutual annihilation but as a chance—perhaps our last—to perpetuate the race. His position is that if we can no longer take to the hills, perhaps we can take to the planets. “In olden days,” he told me, “a defeated people could always find a new green valley in which to start life afresh, but that is hardly feasible today. I see but two approaches to our plight. One is to reduce human destructiveness through some international plan. The other is the old one of finding a new green valley, of expanding the range of human habitat, and this can be done only through astronautics. People sense that the race is in peril, and this, I believe, is a powerful, if unstated, reason for the widespread interest in space and space travel.”

Colonel John Paul Stapp, chief of the Aero Medical Laboratory in Dayton and the man who, a few years back, rode a rocket sled at nearly the speed of sound, suspects that “survival euphoria” may be at the bottom of it all—a desire to win out over the near-death that a space journey would involve. “The Chinese say that narrow escapes are like cutting off the Devil’s tail,” he told me, and I was not surprised when I learned later that he has already volunteered to go into space if and when the time comes. A colleague of his had a less adventurous approach. “Live, intelligent individuals have got to go up or we won’t get the information we need,” he said. As for General Ogle, he told me that the urge to send a man up is largely explained by half a sentence from the President’s Science Advisory Committee’s “Introduction to Outer Space,” a White House document issued last spring: “... the thrust of curiosity that leads men to try to go where no one has gone before.” Then, perhaps visualizing a man in space with an algae garden and a still unknown defense against weightlessness, he invoked another quotation, this one from Einstein: “The fairest thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the fundamental emotion which stands at the cradle of true science. He who knows it not and can no longer wonder, no longer feel amazement, is as good as dead.”

ROCKETS TO WHERE?

by Judith Merril

“In a free world, if it is to remain free, we must maintain, with our lives if need be, but surely by our lives, the opportunity for a man to learn anything. . . . We need to cherish man’s curiosity, his understanding, his love, so that he may indeed learn what is new and hard and deep. . . .”

“Nobody and nothing under the natural laws of this universe impose any limitations on man except man himself.”

The first quotation is from an interview with J. Robert Oppenheimer in Look magazine last year. The second is from the “Three Fundamental Laws of Astronautics,” as set forth in a publication of the American Rocket Society by Krafft A. Ehricke (theorist-designer for the General Dynamics Corporation, and the man responsible for much of the planning that has gone into our ICBM’s, as well as the solving of the re-entry problem and the new plans for a manned orbital vehicle).

Taken together with the words of the late Albert Einstein at the close of the preceding article, these excerpts comprise a potent statement of the essential philosophy of the scientist, a philosophy which has perhaps become essential to all thinking citizens in the “Age of Space.”

The sense of wonder, the desire to know; the will to work at finding out; freedom to learn—but even more vitally the inward freedom implicit in the conviction that man’s capacity for curiosity and for endeavor is the only measure of his potential growth: these are the tenets of world sanity and human survival now. (As ever—but now more than ever.)

To the extent that we can cherish curiosity (learn to question the obvious, rather than accept unthinkingly), cherish understanding (the why? and wherefore? . . . not just the who-what-where-when-how) and cherish love (learn that we need each other more than we need fear each other)—to the extent, in short, that “scientific man” can become thoughtful man —to this extent only can we hope to outlast our own powers of destruction.

I understand that a new model Detroit automobile takes eighteen months or more from the drawing board to the dealer’s display room. It is eighteen months, as I write this, since the launching of Sputnik I. In that brief time, we have witnessed so many further “breakthroughs” on so many scientific fronts (not necessarily connected with space flight at all) that to attempt even to summarize them here would be absurd. (The headline in my morning paper said today: PIONEER IV NEARS MOON ON WAY TO DATE WITH SUN!) The record of physical accomplishment, here and abroad, has been so steadily spectacular that I think most of us have lost the faculty for amazement —at engineering feats. But there is still cause for wonder (and lots of it) in another sphere—and that is in the unmeasured, and as yet barely recognizable capacity of the human being for intellectual, spiritual, and emotional attainment.

“The readjustment of attitudes toward the universe” made necessary by the immediate prospect of space flight was compared to “the beginning of the readjustment of man to a round instead of a flat earth,” by The New York Times’ science writer, Richard Witkin, just last year.

I do not think he overstated. And what he asked for was not far short of a miracle—considering that the four hundred years since Copernicus has been inadequate to sell mankind in general on the existence of the solar system.

Not even that comparatively small segment of humanity that we call “Western Culture” was entirely convinced. At least, one generation back, in Arkansas, a teacher could— and did—lose his position for instructing his pupils in contradiction of Solomon’s clearly stated biblical precept that “the earth is flat, has four corners, and is the center of the universe.” (I quote from the decision of the presiding Justice of the Peace. Whether the Copernican heresy is countenanced today in the same small community just south of Little Rock, I do not know.)

We needed a miracle, and it seemed we were little likely to be given one. (Modern miracles have been moved from the Handout Department to Do-It-Yourself.) The truly amazing and heartening thing is that we are showing signs of producing it—eventually.

The prevailing pre -Sputnik attitude toward space ran a gamut from tolerance to hilarity.

“Before Sputnik, it was considered bad taste for the military to mention space,” Wernher von Braun said in a Life interview.

“The long-time dream of little children has come true,” one Boston paper started its feature piece on the first satellite. Most of the press preferred to say “science-fiction dream.”

A rather self-consciously courageous editorial in Newsweek (for Oct. 21, 1957) proclaimed our entry into the Age of Space . . . “whether we like it or not.” And plenty of people did not —especially if, as seemed inevitable, there would be Russians up in heaven too.

But even in those first few weeks, the job of psychological retooling had begun. The same issue of Newsweek, for instance, carried a full-page advertisement headed, “Instrumentation—stepping stone to the stars”; and under a science-fictiony illustration, in dignified text, came a pitch for the long-range investment policies of the First National City Bank of New York! The New Yorker (dated two days earlier) had an ad with a starmap, a spacesuit, and a map of Florida, saying, “The earth has now launched its first man-made satellite . . . when the rockets take off for outer space ... [it will be] . . . only natural to stop at your nearest ‘moon’ and ask the man for a free Rand-McNally space chart.”

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Year's Greatest Science Fiction & Fantasy 4» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.